5 September 2024 will mark the 30th anniversary of Australia’s supposed first political assassination. In 1994, Cabramatta Labor MP John Newman was shot dead in the driveway of his Woods Avenue home.

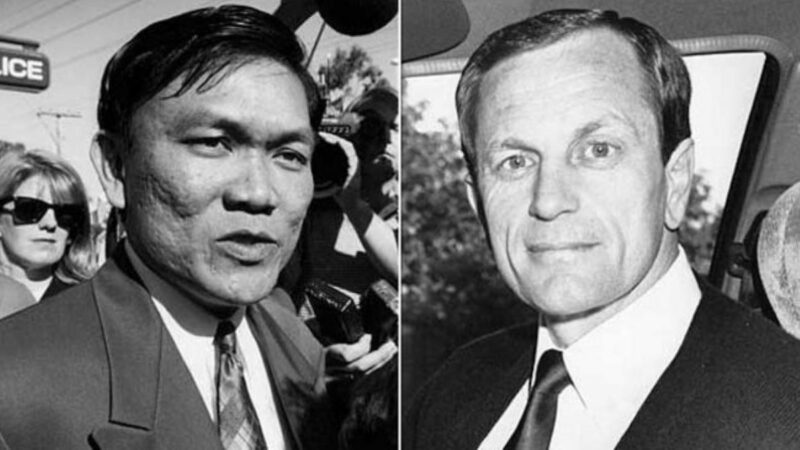

The Sydney Morning Herald reported Newman had received numerous death threats after he publicly advertised to deport members of Asian gangs found guilty of crimes, while also calling for heavier policing in Cabramatta. Ngô Cảnh Phương, a local Vietnamese politician, remains sentenced to life imprisonment without parole nor review for orchestrating Newman’s assassination.

This commemoration demands so-called ‘Australians’ to ponder the emergence of ethnic gang violence within the settler-colony. The common racist belief sees immigrants as innately violent and counter-cultural. In Pauline Hanson’s words, “they have their own culture and religions, form ghettos, and do not assimilate.”

An understanding of racism in Australia necessarily engages with the fact early Australian immigration policy sought to “keep Australia white and pure”. Waves of Vietnamese immigration compromised such fundamental beliefs. In the context of gang activity in Cabramatta, it is essential to understand the turbulent relationship between the Australian settler-colony and the war-torn Vietnamese diaspora.

The Cause of 5T’s Emergence

In the words of the assassinated John Newman, “The Asian gangs involved don’t fear our laws, but there’s one thing that they do fear – that’s possible deportation back to the jungles of Vietnam because that’s where, frankly, they belong.” The rhetorical and military weapon of human displacement, in both the Resistance War Against America, and in Newman’s words, were catalysts to the emergence of Vietnamese-Australian gangs.

Most important to Cabramatta’s history was the emergence of ‘5T’, named after five Vietnamese words: ‘Tình’, ‘Tiền’, ‘Tù’, ‘Tội’, ‘Tử’, translating to ‘Love, Money, Prison, Punishment, Death’. Led by Trần Minh Trí, 5T was founded on a shared trauma of displacement, where mostly boys and men whose families were overseas or killed as a result of war were able to redevelop a local community. These emotions, felt in the context of a racist white Australia, allowed gang violence to manifest as a way of establishing political and economic autonomy.

The rapid growth of 5T and its affiliations threatened the function of local police to the extent where a Commonwealth Parliament Joint Committee formed in 1996 to address ‘Vietnamese Organised Crime in Australia’. Eventually, the suppression of 5T by 1999 has left a Vietnamese community admittedly safer from gang violence and heroin dealing, though wearied and no longer as unified as it once was.

The Gentrification of Cabramatta

Today, Cabramatta appears dramatically different to the narratives of the 1980’s–2000’s. The local history of Cabramatta has been adequately captured by SBS’ renowned series ‘Once Upon A Time In Cabramatta’, however not without implicitly perpetuating the stereotype of Western Sydney’s violence.

Regardless, Cabramatta now inherits a food-based cultural role, mainly advertised through social media. Politically, the region is often analysed as an ideologically conservative voter-base, as identified through voting results in the Voice to Parliament referendum, and the Same Sex Marriage plebiscite. While the community remains severely socio-economically disadvantaged, gradual generational settlement in Australia has helped alleviate the original feelings of displacement which troubled earlier refugees.

The violence of the Vietnamese diaspora is largely unknown in Australian history. Anh Do’s book The Happiest Refugee has become the mainstream understanding of Vietnamese displacement; a romantic story of love and effort overcoming hardship in a prosperous imagination of Australia. It does not confront its white settler readers with the racism they impose onto ethnic immigrants, but instead fetishises a liberal myth of an egalitarian Australia. Vietnamese gang activity still lives in the memories of its local communities – I wrote this article guided by my mother’s childhood reflections. As Newman’s assassination reaches a new decade of commemoration, the immediacy of a trauma caused by war-torn displacement lingers in the background.