Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam, or The World Is Family, blends the personal and the political in director Anand Patwardhan’s retelling of his family’s involvement in the Indian Independence movement. While his collection of oral histories are certainly moving, his politics are perhaps too outdated to confront Facism in contemporary India. Accompanied by a Q&A, the film was introduced with a primer on Patwardhan’s past works, accolades and, most importantly on his politics – in essence a commitment to Gandhian Liberalism.

Filmed across three decades, The World Is Family encapsulates Patwardhan’s quintessential style: spontaneous, organic and unwaveringly analytical. Narrating the early lives and last days of his parents, Pathwardhan presents a refreshingly intimate insight into the feelings of struggle, nostalgia and hope which have coloured key moments in India’s history of independence, Partition and protest. The film’s title itself is an attempt to reclaim this Sanskrit phrase, meaning “global harmony”, from its co-optation by Hindu nationalists. Although some time jumps between past and present-day were jarring, Patwardhan’s use of archival footage is nonetheless a stark symbol of resistance against attempts by Modi’s government to censor this period of history.

Much of Patwardhan’s work is centred around setting the record straight. By retelling their story, Patwardhan’s parents reveal the unity between Muslims and Hindus during the fight for Independence. Critically, Patwardhan foregrounds the millions of working-class Muslims who refused Partition – which they saw as only beneficial to the upper-class Muslims. Unfortunately, it was only the latter group that was permitted to vote in the 1946 provincial elections that led to Partition. As Patwardhan shows, rescuing these historical facts of unity from obscurity remains crucial in combating hyper-nationalistic sentiments.

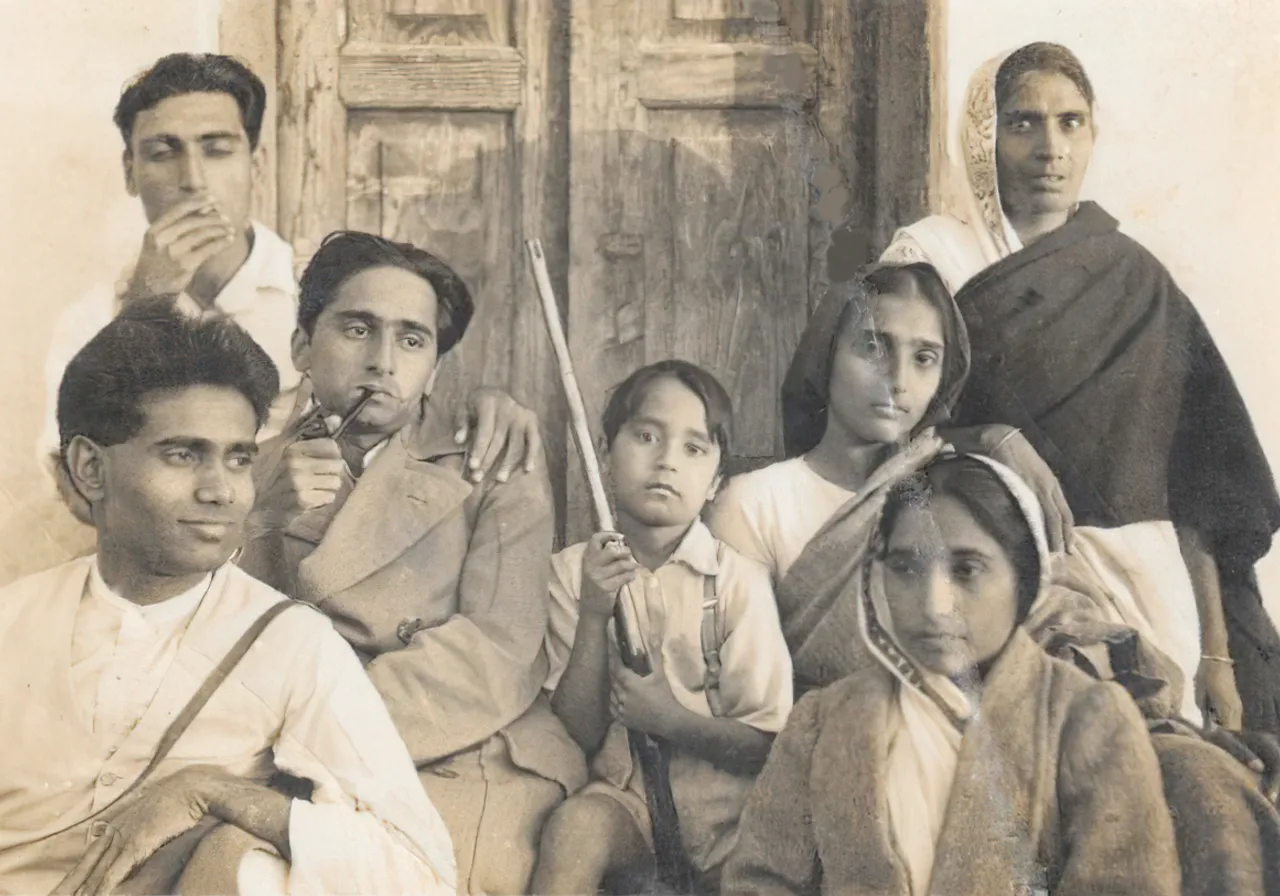

Nowhere is this purpose more obvious than in Patwardhan’s many interviews with his extended family members. Patwardhan’s paternal uncles Achyut Patwardhan and Purushottam Patwardhan feature prominently, with insights from their children demonstrating the multifaceted nature of anti-colonial struggle after Independence. Patwardhan’s mother, Nirmala, also recounts her memories of Mahatma Gandhi, told through a whirlwind of memories ranging from her studies at Shantiniketan art college to how she lost “her most prized possession”, Gandhi’s handkerchief. Recorded through funny outtakes and home videos, these experiences tell the unique yet ubiquitous story of a revolutionary Indian family.

Perhaps the most striking political commentary came from Patwardhan’s chance encounter with two young boys at a local school. While speaking to an old family friend, the group moved to a discussion about the origins of recent religious riots in the area. When Patwardhan asked the Hindu boy which ethnic group started the riots, he responded coyly with “the Muslims.” His Muslim classmate countered with “the Hindus.” Patwardhan, shocked by the boys’ partisanship, queried who had taught them these stories. Their gazes shifted to the older men in the scene, a line of teachers jostling uncomfortably in the background, who recited a worn-out rhetoric of “equality” and “empathy.”

After shaking hands at Patwardhan’s request, the boys admitted that they were not friends. The scene closed with the boys parting in separate directions, one on a pushbike, one walking barefoot through the street.

Patwardhan makes an astute observation here: the same generation that championed freedom and revolution are now teaching the language of division and prejudice they once rallied against. What appears as continuity between the young and the old actually represents a widening separation between the old and the new, manifesting in a co-optation of revolutionary politics and a distortion of truth. Patwardhan shows that this is how Partition is justified, how protest is stifled and how hatred wins out.

Nonetheless, the documentary still finds most of its humanity in its home videos. Family walks along the coast of the Indian Ocean; reunification at a birthday dinner; laughter as wife scolds husband and son; travel time spent in silence on a train to Delhi. These are the scenes which bring The World Is Family to life, those which tell a story even though Patwardhan “did not think [the footage] would be a film.” The relationship between Patwardhan’s parents, a loveable revolutionary and an award-winning potter, lies at the heart of the piece’s emotional impact. While Patwardhan notes that “filming created distance” between himself and the deterioration of his parents’ health captured throughout the documentary, we found their deaths to be the most visceral and touching moments of all.

While the politics of the film are agreeable, the disappointing Liberalism of Patwardhan’s beliefs were centred in the post-film Q&A. After responding to an audience member’s question about how to defeat the rise of Hindu nationalism with a defence of electoral politics, Patwardhan was cut off by another burning question: “what are the masses to do?” Returning to a rather utopian dream, Patwardhan answered by disavowing the possibility of a mass revolt and urging the opposition parties to unite against Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in the upcoming election.

Such talk is reminiscent of the 2016 and 2020 US elections, where the democratic candidates – no matter their own political depravity – were seen as the bulwark against Facism. With another victory for Trump likely this year, one can easily see how effective the electoral strategy is; it failed the Muslim workers in 1946, and it continues to fail them today.

When retelling this history, one must also remember that it was this electoral system that put Modi in power – it is dubious to think it will defeat Facism.

Despite a commitment to analysis when filmmaking, Patwardhan’s also presents Gandhi’s actions and political positions uncritically. There are other histories to be told here, revolutionaries who understood the shortcomings of Gandhi’s politics. We do not blame Patwardhan for not having a family so extensive that he could personally reproduce the entire history of India’s Independence Movement. However, his assertion that the film is important for the nation to see must be qualified. A figure like Gandhi, so aligned with the Liberalism that brought India to Modi, is not the figurehead who will help defeat him. Patwardhan’s Liberalism is exemplified by his appeal to rationalism: for him the battle against Facism is simply a battle for reason. But Modi does not represent irrationality. Instead, he represents the interests of the Hindu elite. The Gandhian political philosophy of dedication to nonviolence and satyagraha – ‘appeal to truth’ – are ill-suited to the current task. As Bhagat Singh teaches: “non-violence is backed by the theory of soul-force in which suffering is courted in the hope of ultimately winning over the opponent. But what happens when such an attempt fails to achieve the object? It is here that soul-force has to be combined with physical force so as not to remain at the mercy of a tyrannical and ruthless enemy.”

Patwardhan ended the Q&A with a call for a new freedom struggle – perhaps it’ll require a new and radical politics.

This screening of The World Is Family took place at 4pm on February 10, 2024 at Dendy Newtown. It is a part of the Antenna Documentary Film Festival, running in Sydney between February 9 – 19. Alongside a program of over forty other documentaries from around the world, Patwardhan’s documentary was shown again at the Ritz Cinema in Randwick on February 17.