The experience of being the only one to pull weight in a group assignment is unfortunately one that is all too familiar to me. This is to say that Andrew Scott’s decision to star in a one-man production of Anton Chekov’s 1897 tragicomedy Uncle Vanya made perfect sense.

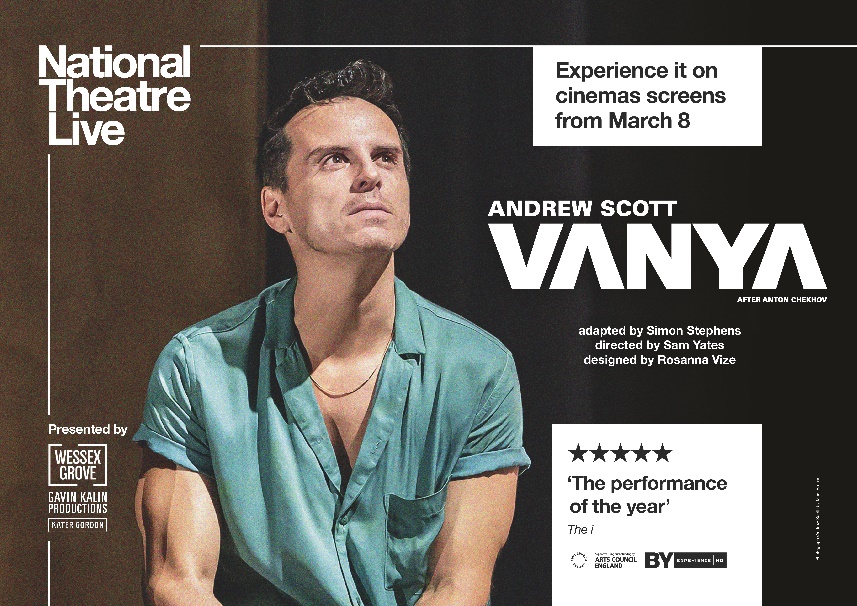

Co-created by Scott, playwright Simon Stephens, director Sam Yates, and designer Rosanna Vize, this adaptation instigates a few changes to the original play to reframe it for contemporary audiences — the play’s name is shortened to just Vanya, the performance is entirely in modern vernacular, character names are anglicised with the setting befittingly left up to audience imagination and discretion, and of course, Scott plays all eight roles.

Such reframing does not take away from the source material in any capacity. From unfulfilled potential to existential malaise to environmental destruction, all the main Chekovian themes are touched upon, though some are explored more in depth than others. Moreover, the love-quadrangle involving Helena, the beautiful and much younger wife of ageing screenwriter/filmmaker Alexander, Alexander’s daughter Sonia, weary doctor and amateur conservationist Michael, and the titular Vanya (named Ivan here) remains the play’s focal point.

Considering the major selling points of the original Uncle Vanya are the interactions, or lack of them, between a slightly eccentric group of characters in a strange sort of emotional liminal stasis Vanya shouldn’t have worked as well as it does.

Scott is seamless in his transitions, giving brilliantly controlled, and physically considered, performances. Each character he possesses is differentiated symbolically and by change of voice: Helena is posh, and fidgets constantly with her necklace; Ivan bemoans around the stage in a pair of dark sunglasses; Maureen somehow always has a cigarette between her fingers. There’s also an odd humour in seeing Scott conversing, romancing, and fighting with someone who is never there, at least in the physical sense.

Watching Vanya in this iteration also involves paying close attention to every minute detail that is happening on stage; one small look away leaves you out of the loop. I will note here that having some knowledge of the original play is useful to have in your pocket. It feels fitting to say that the play unfolds here as if you were reading a book — you take note of the characters, their idiosyncrasies, and interactions to piece together a final picture of where the story will go and how it will unfold.

There is, of course, also the oddity of seeing a filmed version of a theatre performance. What I love most about live theatre is the atmosphere, the anticipation of seeing someone happen immediately before your eyes. The film medium does take something away from that, especially in being able to fully take in and consider the set design which features a mirror that I assume reflects the audience, though I do appreciate being able to see a West End performance without having to fly to London to do so.

National Theatre Live — Vanya plays in select cinemas from March 8.