“[My father] shoved aside my bowl of receipts, setting up his things on the bar. “I just want to let you know,” he said, “I call the shots. You sit right there in that chair and I’ll tell you what goes on.”

I looked at him with a growing sense of horror.

“I’m Britney Spears now,” he said.”

(pg. 175)

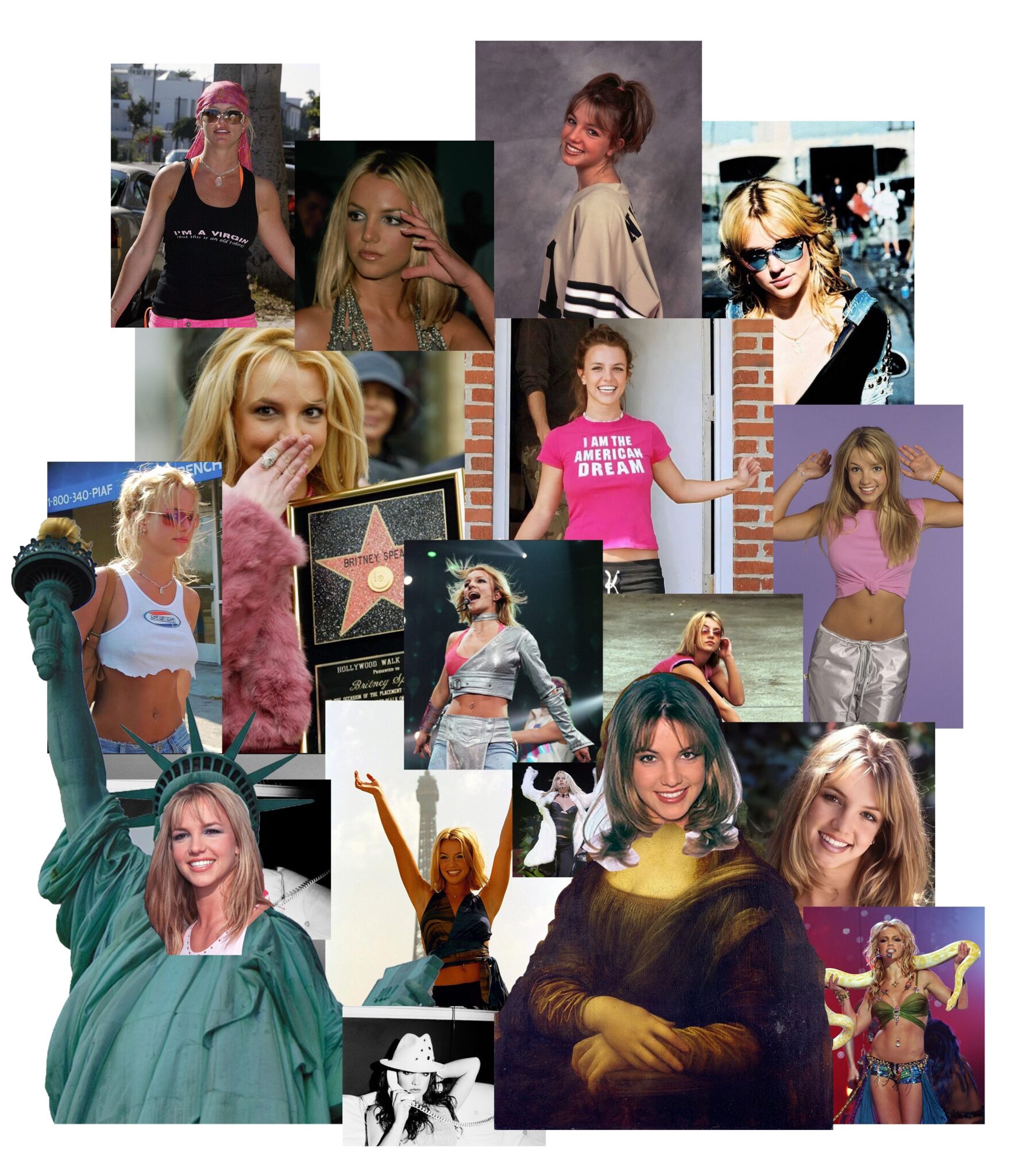

In her memoir The Woman in Me (2023), Britney Spears revealed that she kept a bowl of receipts to calculate her taxes in an attempt to retain her sense of independence under an oppressive conservatorship. Her father and many other individuals complicit in the conservatorship disagreed. This desire for financial autonomy only confirms how her human rights became alienable, namely in the thirteen years of control spanning from 2008-2021.

You may be thinking, why should I know about this — didn’t the conservatorship end three years ago? Acknowledging abuse and being able to identify it is itself a form of power. It is a privilege to have the capability to advocate on behalf of others.

And if it can happen to Britney, it can happen to anyone.

“My life has been so overprotected”

For those who followed the #FreeBritney movement, the majority of revelations about the conservatorship in her memoir were not new. However, hearing it from the person experiencing it confirmed the investigations of fans and human rights advocates alike. The Ebadi Declaration flew under the radar, despite putting forth allegations of surveillance, financial control, and medical abuse. This was confirmed by Britney’s court testimony, where she detailed how she was placed on lithium, compared her seven-day weekly schedule to “sex trafficking”, deprived of her privacy, and was even forbidden from removing her IUD when she requested to do so.

It is easy to classify #FreeBritney as a mere celebrity struggle, yet it is inseparable from any other human rights abuse. Britney was not the typical candidate for probate conservatorship of the person and estate as she was not old — she was 25-years-old — or with dementia or disabled. She also was not allowed to choose her own court-appointed lawyer to represent her throughout the conservatorship, and found out years later.

Even criminals have the right to choose their own attorney.

Many people don’t realise that the conservatorship case is still active, with the next court date on April 5. While Britney is no longer under a conservatorship, there are loose ends to be tied up, including how the conservatorship came to be. There have been back-and-forth petitions, depositions, mediations, discoveries, and hearings, many related to Britney’s finances/accounting in the lead up to a trial in May. In short, Britney still has to simultaneously contend with the aftermath of the conservatorship as well as court delays.

“I was born to make you happy”

It is worth noting that Britney is a privileged individual as a “white, wealthy, cisgender woman”. However, it is this hypervisibility that has brought conservatorships and disability rights to the forefront of discourse.

Britney was under a probate conservatorship which concerned both her person and her estate. In other words, her body, health, living arrangements, motherhood, career, income and assets were all decided upon by others. Britney, supposedly ‘incapacitated’, continued her career while being inhibited from decision-making across every aspect of her personal and professional life.

While there tends to be a preference for family members to become conservators, in Britney’s case, it was her family who had financial interest in her and so benefited from her loss of freedom. This almost happened to Lindsay Lohan, Elijah Williams, son of Cher (ongoing case) and it happened to Amanda Bynes (now free from her conservatorship) and Wendy Williams. Besides Wendy Williams, there is a pattern here: children-turned-stars thrust into the limelight.

Despite having an illustrious career, by 2018, Britney was worth $59 million (only?), whilst it has been reported that the individuals, business stakeholders and legal personnel involved in the conservatorship were on her payroll. That same year, Britney spent a total of $1.1 million on legal fees, with $128,000 going to her father, the conservator.

“They want her to break down, be a legend of her fall”

While conservatorships are not present in the Australian context — they are called guardianships — similar concerns apply. Hannah Shotwell says that guardianships derive from the “English common law concept of parens patriae, in which the state is obligated to care for those who cannot care for themselves.” Yet that doesn’t always translate into practice.

An ABC article in 2022 by Anne Connolly quoted a lawyer saying, “When people with a disability approach me as a lawyer, they express a sincere and genuine fear of ‘the government’, as they call it, which is the Public Guardian and Public Trustee, coming to make decisions for them.”

In what is referred to as “state control”, guardianships are also seen as a last resort, however family members are not the preferred candidates for this conservator-like role. Instead, public guardians and trustees are appointed.

Media coverage of guardianships is limited due to the gag laws in place which make it illegal to identify someone “even if their order has been revoked or they have died.” Family cannot speak publicly, and there are penalties, including thousand dollar fines and prison sentences.

As for Britney’s family, she emphasised that “the people who did that to me should not be able to walk away so easily” and that her “dad and anyone involved in this conservatorship and my management — who played a huge role in punishing me… they should be in jail.”

This has yet to happen.

While scholarship suggests that not all conservatorships are bad or ill-conceived, I struggle to contend with how someone may have another’s best interests at heart if they are simultaneously benefiting from it. It may not always be the case but there is a long way to go for legal and ethical reform.

“I’m Miss American Dream since I was 17”

Honi Soit contacted Kate Leaver, ex-Honi editor, who in 2008 wrote a feature on Britney at the height of anti-Britney press.

In a media lecture called the “Putting The Brit in Celebrity”, Leaver realised that fame and popular culture “could be — and should be — studied” and “what it meant for the way we were valuing (or not) the lives of the people who entertain us.” She noted that while Britney’s career and conservatorship were not of particular concern to her peers — something I have realised as well — it is “the intersection of mental health, exploitation, abuse, feminism, fame and the horrors of paparazzi culture” that drew her to the case in the first place.

When I made a generalisation asking about whether ‘the media’ is still complicit despite backtracking on its treatment of Britney, Leaver made a valid point that there is a new generation of journalists being ushered in who acknowledge these “damaging systems”, and even try to dismantle them. I realised that it is not always helpful to have one source of blame, even if the media was a big contributor to the anti-Britney frenzy of the late 2000s.

Leaver also said that there needs to be specificity when discussing “exploitative” narratives of women in the spotlight, delineating between those circulated by tabloid outlets versus individual journalists. It was deemed particularly important as female celebrities continue to be subjects of unethical pieces where they are portrayed as a culprit, especially when compounded by the intersections of race, class and sexuality.

As such, we often raise public figures only to “tear them down” when the pendulum of public opinion swings back. I came to the realisation that what we discuss amongst our friends, our family, at dinner tables, on Twitter, provides the motivation for media coverage, and that we cannot be insulated from the institutions that speak for the people.

“That’s my prerogative”

After her conservatorship ended, Britney wrote on Instagram, “I’m just grateful for each day and being able to have the keys to my car and being able to be independent and feel like a woman…Owning an ATM card, seeing cash for the first time, being able to buy candles.”

We, as a society, have always been fascinated by Britney Spears, while this was detrimental back in 2008, it also led to the #FreeBritney movement moving from a conspiracy to a credible social movement.

Yet everything can turn into a double-edged sword, with many onlookers hesitant to let go of this saviour-like and paternalistic support, criticising Britney’s social media usage based on concerns for her well-being. As such, Britney’s Instagram posts are used to recycle the expired narrative that she is ‘crazy’, and therefore deserved to be controlled.

On multiple occasions, Britney has stated she does not want to return to the music industry. Yet, many onlookers — media and public alike — insist on expressing our opinion on what she should or should not do. I believe we are not entitled to demand her return.

I also recognise that by saying that, I am engaging in the very thing I claim to despise: giving an opinion on Britney’s life. We, as a society, have always been fascinated by Britney Spears, while this was detrimental back in 2008, it also led to the #FreeBritney movement moving from a conspiracy to a credible social movement.

But for someone who has experienced traumas under the conservatorship — and beyond the conservatorship — Britney should be able to live her life freely, with as little input from people who did not live her life.

And Britney Spears is Britney Spears. No one else.

#justiceforbritney #letsgettoworkbitch