The presence of the New South Wales (NSW) police and their uniformed participation at this year’s Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras was rightfully contested following the alleged murder of Jesse Baird and his partner Luke Davies by Senior Constable Beau Lamarre-Condon. Initially, the Mardi Gras Board withdrew the police force’s invitation to participate, but an agreement was later struck enabling them to march in plain clothes. This reversal faced wide criticism and the police further ignored the compromise, marching in police insignia.

This situation raises concerns about the symbolism of police uniform, begging the question: why do police continue to insert themselves into queer spaces?

It’s well-known that Mardi Gras started as a protest. In solidarity with protests in the US, the Gay Solidarity Group organised a march in 1978 followed with nighttime celebrations on Oxford St, during which the police arrested 53 people and beat many others. Many of those arrested lost their jobs, homes and even took their lives as the police offered names and addresses to the media. NSW police did not apologise to the original 1978 marchers until 2016.

Then, in 1998 the police marched in the parade for the first time, despite backlash from the queer community. This opposition has continued and gained momentum, with many activist groups continuing to fight for the exclusion of the police from Mardi Gras. Last year, former Greens senator and activist Lidia Thorpe yelled “f*** the police” and laid in front of the police float, temporarily halting the protest.

In the wake of the murder of Baird and Davies, tensions between protestors and police have flared once again. It’s telling that the catalyst of the Mardi Gras Board’s decision was not the increasing deaths in custody, police violence against First Nations or consistent First Nations protest against police presence.

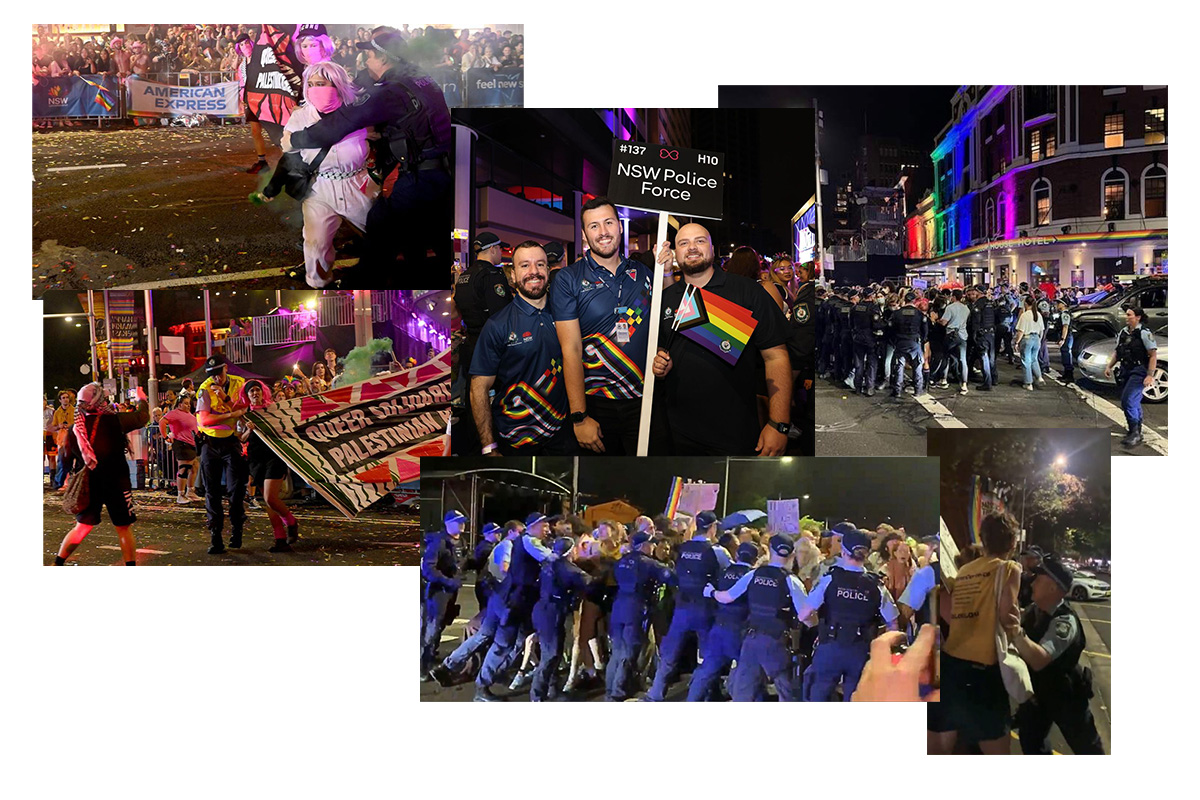

Tensions between the police and queer community culminated, on the eve of Mardi Gras, with a protest in Taylor Square. The organiser of the demonstration, queer activist group Pride in Protest, posted videos of police assaulting protestors and reiterated that the inaugural Mardi Gras was a protest. The police’s force brutal police violence of 1978 cannot be separated from this year’s.

Despite this community outcry, blue uniforms stained Saturday’s parade. During the Parade, booing from the crowd ricocheted through Oxford Street as the police force began their march. The police contravened the compromise request to march in plain clothes; the marching police wore an alternate uniform to field dress –– blue polo shirts, inscribed with the Progress Pride flag, the police force logo and NSW Government logo. Many onlookers were shocked to notice uniformed riot squad officers flanking their police colleagues who marched in matching navy blue shirts.

Beyond this, uniformed police occupied Oxford St and surrounds, under their “highly visibility operation [sic]” entitled ‘Operation Mardi Gras’. These officers pushed the dark irony of the situation further, forcefully arresting pro-Palestinian protestors. Under their banner “Queers in Solidarity with Palestine”, activists intervened in the Labor float with chants and red, green, black smoke flares. Photos of the situation depict a mass of riot squad and field dress officers descending on these individuals. Eight protestors were arrested and charged with “more than three people use violence to cause fear”.

This situation makes sense in the legacy of police brutality of queer and marginalised communities. The police marching in an alternate uniform does not negate years of traumatic history between the community and the police. Pride in Protest illuminated this, stating, “we have watched our friends be brutalised by them. No cops at Mardi Gras, this year, or ever again.”

To marginalised communities, the police uniform has become synonymous with excessive force, mistreatment and discriminatory behaviour. The decision to allow police to march in plain clothes ironically recognises the symbolic nature of the uniform as a display of power, particularly as full uniform includes a police-issued gun, alleged to be Lamarre-Condon’s murder weapon. Uniforms represent colonial and political authority, and their ease of recognition thus visually legitimises discretionary and excessive force.

In recent years however, this ‘social skin’ of disciplinary power has extended into the colour blue itself, with the countermovement ‘Blue Lives Matter’ emerging in 2014 in opposition to the Black Lives Matter movement. The power of the police uniform itself is acknowledged by the existence of laws penalising the misuse of police insignia.

It therefore becomes difficult to ignore the decision of officers to don an alternate uniform of matching navy blue shirts as their choice of ‘plain clothing’.

Anti-police protesters argue safe spaces are intentionally exclusionary towards groups that the space was not intended for. The police’s presence at Mardi Gras, whether uniformed or in plain clothes, will remain highly contested while the police meter out injustices and violence to queer communities.

This political situation brings history onto our confetti-lined inner city streets. And so, Prime Minister Albanese’s statement, “Australia has moved on from [police violence towards queer people]”, is proven false. Ultimately, many members of the community, both queer-identifying and allies, are left convinced that police participation during Mardi Gras did nothing to hide the presence of pigs in sheep’s clothing.