It is Week 6, the last week before the mid-semester break. Most likely, that entails a heavy flow of assessments and an even heavier flow of resentment towards the business of education. In this daze of revision, tears and USU coffee, how many of us forget our privilege? For 12% of students, the first in their family to undertake a university qualification, higher education is an unlikely opportunity. But it’s not something they’ll be rewarded for. Elitism remains entrenched in our tertiary education culture. Who decides who will make it within these hallowed halls?

It was this week at Courtyard Cafe that we, the writers, were shocked to discover that we had not encountered anyone else at the University of Sydney (besides each other) who are First in Family (FiF) students. Often the statement, “no, my parents didn’t go to uni” is met with an uncomfortable glance, as if one has just bared their soul, or at the very least, their income bracket. Aside from social stigma, structural prejudice means that adjusting to university administration and bureaucracy proves an additional challenge. When enrolling in a unit or selecting a tutorial before stepping foot on campus, it can be helpful if someone in your household knows what a ‘unit’ or ‘tutorial’ actually is.

FiF students are those who are the first of their parents, siblings and grandparents to attend university. This semester, 11% of students enrolled in a popular introductory core unit of study at the University are FiF. That’s 20 students in a cohort of 182. According to the University of Sydney’s 2021 Student Diversity Report, 12% of currently enrolled students are grouped in this category. Furthermore, the University reported in 2020 that the number of prospective FiF students who preferred it as their first UAC choice increased by 11% from the previous year.

Viewed in isolation, these statistics appear to indicate that there are fewer FiF students in Australia than ever before because tertiary education is increasingly accessible, and that the University itself has played a key role in facilitating this inclusivity. However, these assumptions are incorrect. The remainder of the Student Diversity Report shows that more than 60% of all undergraduate students live locally, and that 35% of this cohort graduated from independent schools. When compared to an institution like the University of Western Sydney, where more than 65% of students are FiF, these figures show a clear continuation of USyd’s elitist origins.

If the University is reluctant to admit that it has a class diversity problem, it is even less interested in providing tangible and meaningful solutions. Although few students are aware of it, the University does offer what it markets as a First In Family Mentoring Program. However, this Program is only available to Economics students, and students must apply directly to the School of Economics with their CVs for consideration.

Rather than helping students find their community or foster meaningful relationships with academics and industry professionals throughout their degrees, the program is also only targeted at first-years to “provide support to find your direction and plan your career.” These technical and bureaucratic concerns, such as the rigorous requirements to meet with one’s assigned mentor once a month and submit two reflective journals during the Program’s duration, reinforce the University’s focus on maximising its image and profits at the expense of student welfare.

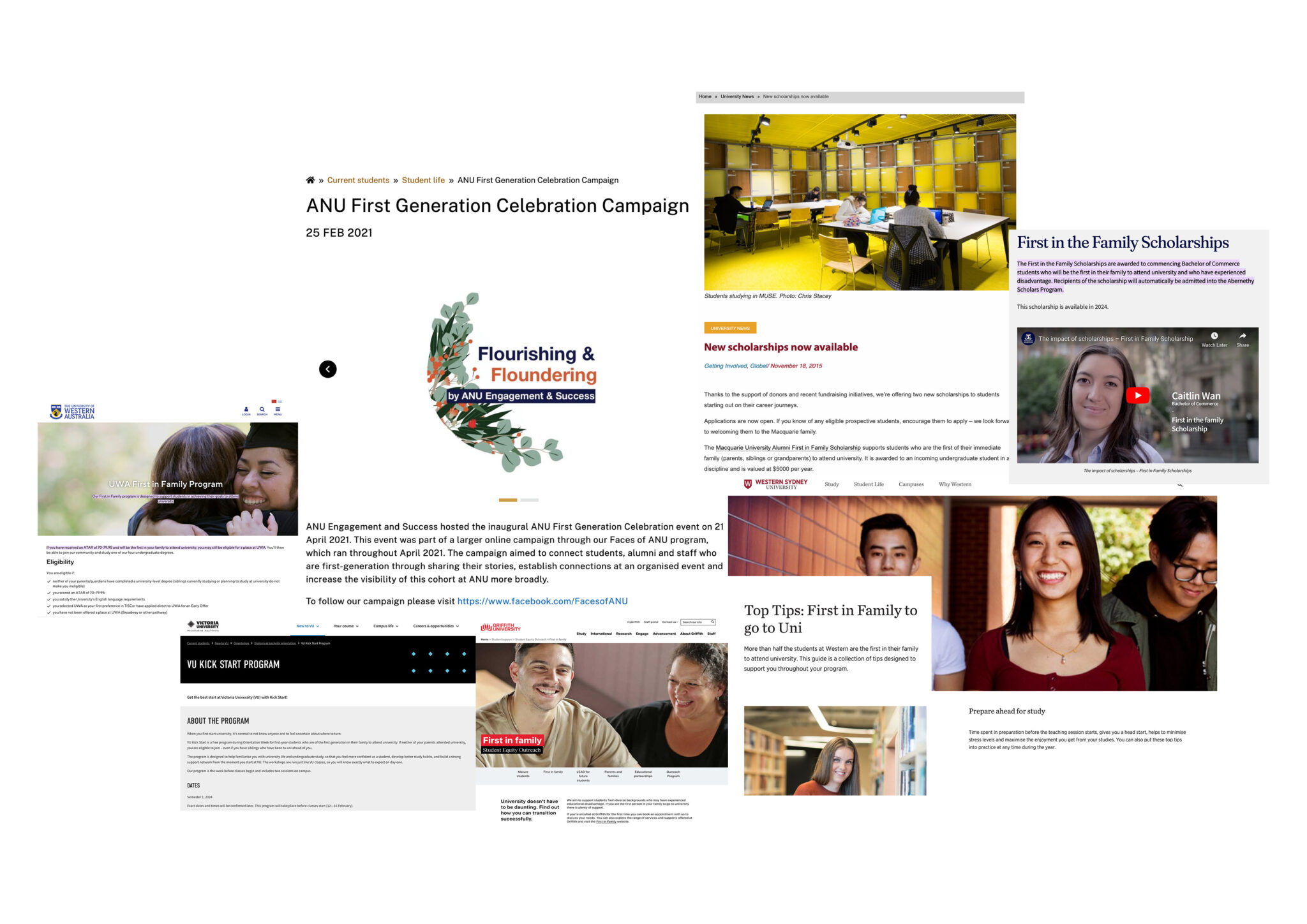

That we had never heard of this Program, and that it appears to be the only initiative on offer for FiF students, is a testament to the University’s lack of transparency and lag behind other institutions. At the Australian National University, FiF students are supported by a pastoral program called the First Year Experience (FYE) which connects students socially to foster a sense of belonging and community. Reflecting on this, one ANU student remembered, “being part of the first generation community at ANU, I have made lifelong friends.” Similarly, FiF students at Macquarie University are financially supported by an annual bursary of $5000 for undergraduates in any discipline.

Socially, breaking through the shiny veneer of alma matters and ‘old boys’ clubs is quite the feat; one must only look to the enduring status of the Colleges on-campus for a sharp reminder. But does this become even more difficult for female FiF students? A 2022 study monitoring FiF students at the University of Queensland showed significant challenges on the intersection of gender. The study found a staggering 40.9% of female FiF students encountered mental health challenges while studying, in comparison to just 3.8% of their male classmates. Additionally, it found that female students’ academic aspirations were more closely linked to achieving the opportunities their mothers missed out on.

As women who have completed a cumulative total of seven years at university between the two of us, we have taught ourselves everything about tertiary education that the system failed to do itself. But as we prepare to embark on our respective careers, the path is no clearer. Looking to the future, there is a clear need for more comprehensive pastoral care programs as well as the construction of a more positive narrative where FiF students are celebrated, rather than alienated.