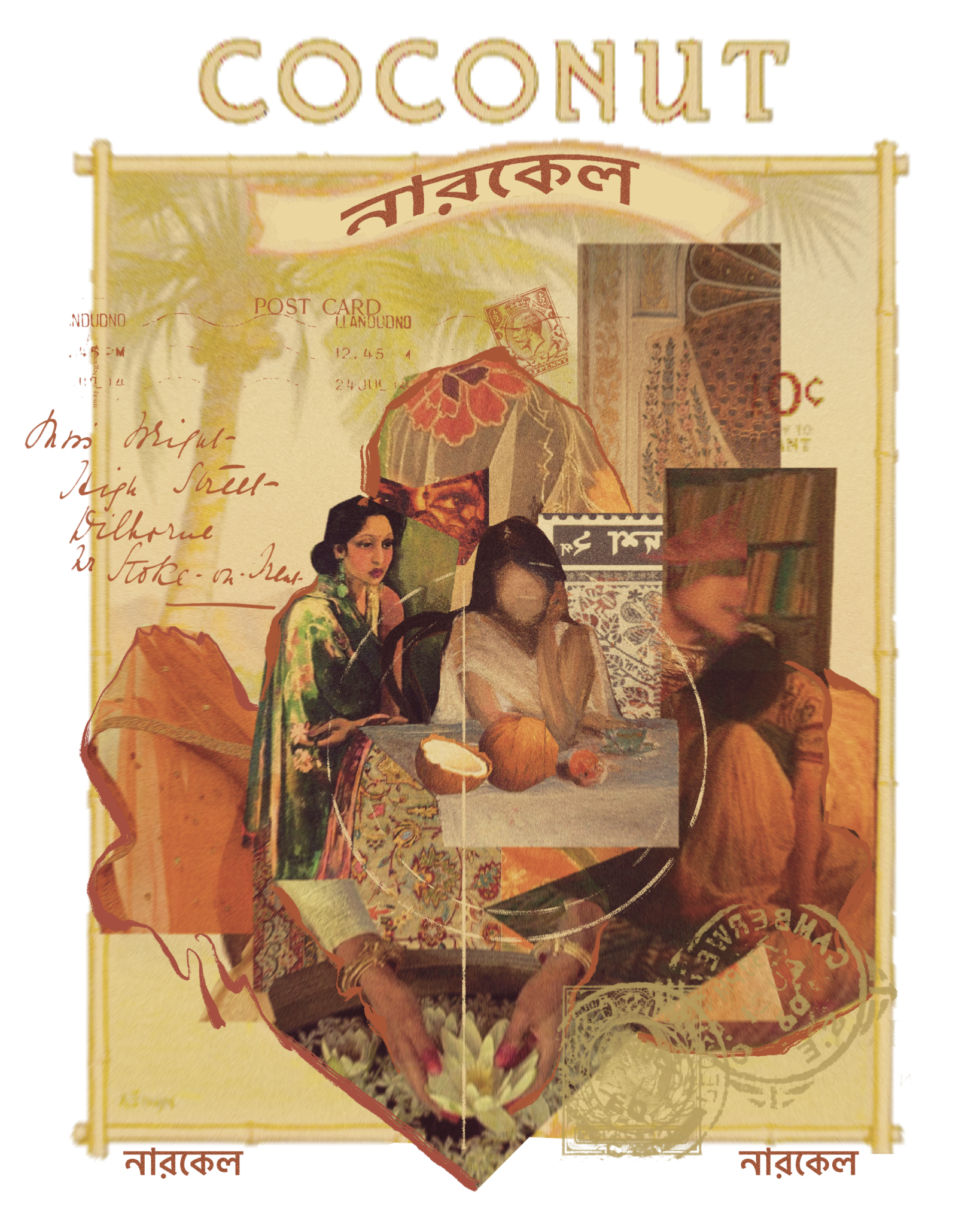

My acceptance into the Sydney College of the Arts (SCA) was quickly followed by the label ‘coconut’ – meaning I was brown on the outside, but white on the inside – and the immense weight of my desire to fit in with what I knew would be a predominately white cohort. It was as if I were hanging in the balance between two communities, my perceived ‘whiteness’ ousting me from one community, and my ‘brownness’ placing me on the outside of another.

The consensus amongst my family was that I was already well on my way to becoming a hip Newtown art kid; I was enough of a ‘coconut’ to fit in, I had nothing to worry about. This should have been comforting, had it not translated to simultaneously not being ‘brown’ enough, as if I could adorn myself in the cultures and colours of my ancestors as much as I pleased, but the unconventionality of entering a predominately ‘white’ space, such as a western art school, ensured I would never truly speak the same language as my brown community.

The irony is that I’ve found that I cannot make myself ‘fit’ in the community that earned me my ‘coconut’ title, without feeling like a big, bad, brown imposter within the walls of the SCA.

We walk the halls of our art school and down the streets of art-dense (and notably white) local areas, such as Newtown, and see South Asian culture at any given turn. The paisley skirts and thread-woven bags, the elephant motifs, and kameez-turned-dresses. The Indo-chic aesthetic has become synonymous with ‘art kid’, which has always been synonymous with ‘white kid’, to the extent that the culture from which the aesthetic is derived holds no claim over it. Now, it belongs to the ‘white body’ which models it across the art world. The kameez I’ve brought from Bangladesh begins to feel like a costume, a weak attempt to fit in with the authenticity of the thrift and ‘depoped’ culture.

Trying too hard to be seen yet attempting to blend in – it feels impossible to do either when you are one of the few South Asian students in the cohort. The few of us who do stand right in the heart of this world of art watch our culture in fragments all around us but never see its people. Brown kids in art school is not a concept that is encouraged on either side – the issue of art spaces in our Western society being inherently for white people is a prevalent assumption across the board. Thus, we continue to dwindle in numbers and exposure on the outskirts of either community, not quite knowing where to ‘fit’.

There isn’t an exact science as to why brown kids feel out of place amongst white peers, regardless of whether you dress the same, talk the same, find similarities in your passions, and share spaces. Much of it, I suppose, boils down to the internalised insecurity we’ve been raised with of ‘fitting in’ within our harshly white society. We have carried the presumptions and boxes used to categorise us back on the primary school yards into our university classes.

I believed my identity crisis was done and dusted after excruciating Eastern Suburbs high school years, feeling myself finally grow into my brown identity. I was daydreaming of a wider world waiting, where I was not 1 of 6 brown students in my cohort. Yet, entering art school, I have found my cohort has gotten increasingly larger, and the number of brown kids in it has shrunk further.

I feel at home within a space that encourages creativity and self-expression and offers the privilege of painting for hours on end. I appreciate (almost) everything that attending an art school offers. No one belittles passion, and no one limits our crafts down to frivolity; there is this single nuance that I share with everyone as an art student, and it does (almost) feel like belonging. Despite that, I feel like a stranger, to both myself and this community I am building within the SCA walls. I often take on a more curated personality in our interactions, one which subconsciously omits the ‘brown’ from my experience and plays into the ‘white’ of my ‘coconut’ identity. It is only within my art that I bring my South Asian identity, experiences, perspectives, or culture to the foreground of my ‘art school persona’. My brown identity is either on exhibit, a tool to exoticize my conceptual framework, or something pushed to the back of storage for when it isn’t required to be gazed upon.

This sense of un-belonging is not new. My high school friend circles have majorly consisted of white, artsy kids (who, I must note, would fit in seamlessly in the art school environment). It was through a shared love for art, and each other, against the angst of teenagehood that the isolation was a comfortable one. I had never felt unseen by my friends who had witnessed all the intimacy of growing up. Now, in my early adulthood, surrounded by those who haven’t been placed in forced proximity with my ‘brownness’, I am beginning to feel the loss of connection with the people who speak my language. I feel tethered to them, trying to make my way to them, the people who look like me, who share experiences that are inherent to us. I keep looking for them and keep finding them in the chemistry/pharmacy/health buildings on campus. They keep trying to convince me to ‘join their side’.

The thing about cliques is that they run on both sides.

The expectation in brown communities to cling to the prestige offered by STEM degrees is matched with Western stereotypes and assumptions that brown people are bound to become our doctors, engineers, and IT guys. Thus, pursuing creative degrees within the brown community makes you an automatic outlier. A brown Med student once playfully asked me “No, what do you really do?” when I told him I was studying Visual Arts. It’s a running joke, a brown girl at an art school. The unwritten rule states that the white kids belong to the Arts and the brown kids belong to STEM. Cliques are tight knit, and you find you don’t entirely fit into either side.

I almost quit art school in my first year, convinced that the community I was searching for might be found in the trenches of the STEM degrees that I had no interest in. I thought that it would at the very least rid me of the confusion and concern in the eyes of aunties when I told them of my studies, and that would be enough for me.

Yet, looking back on my art, so much of which is based on my cultural experience and identity, I understand I couldn’t just leave it behind. If we do not write ourselves into the art world, we will be written off. And I won’t be the reason there is one less brown kid taking up space in these art-filled halls.