Yumna Kassab is a writer from Western Sydney. She studied medical science at Macquarie University and neuroscience at the University of Sydney. Her first book of short stories, The House of Youssef (2019), has been listed for prizes including the Victorian Premier’s Literary Award, Queensland Literary Award, NSW Premier’s Literary Award and The Stella Prize. Her writing can be found online at Kill Your Darlings, Sydney Review of Books, Peril Magazine, Meanjin, The Sydney Morning Herald and Mascara Literary Review.

Yumna, the teacher and creative

To start off, in the “people also asked” section on Google, two questions stood out: Who is Yumna Kassab and why does Yumna Kassab write in cafes? Could you describe who Yumna Kassab is, beyond her identity as an author and educator? And more importantly, why do you write in cafes?

I was going to say Yumna Kassab is a writer from Western Sydney, but that’s a very difficult question. How did you come up with this question? Before culture, language, anything part of my identity, most of my references are literary. I do think writing is literally how I think and I interact with the world. Joan Didion says that she writes to figure out what she thinks and for me, it’s very similar. Everything’s clearer when I write what I think. Writing in cafes started many years ago when I was figuring out a process for writing. During high school and university, I would write at home in the evenings. But the cafe, it takes me out of my routine environment and I am less likely to be disturbed. It also is very stimulating without me needing to interact with others. But a good cafe for eating is a very different cafe to one for writing because the ones that are very popular don’t make good writing cafes. Also the coffee has to be good and I prefer it in a proper cup, not a takeaway cup.

One of Honi Soit’s editions tackled the myth of Australia, whether that be the rural-urban divide, or the Australian literature scene. You wrote a book called Australiana and have taught in regional NSW. What is something that you find overstated in the discourse about what it means to be Australian?

This is a broad comment but when the shortlist for the Stella Prize was announced, it was noted that 25% of the books published in Australia are by writers who are based in regional areas. I don’t know how into crime fiction you are, but these are the books that are set in regional areas. Something I noticed living in Tamworth is that often regional communities have city people speaking on their behalf or speaking over the top of them or saying this is what suits that community. There’s a comment in Australiana where some people think that the Blue Mountains is the countryside, and I strongly disagree with that original comment. I do think that not many people from the cities spend a lot of time in regional areas. That’s always interested me because my family are farmers in Lebanon, which is obviously in and of itself different from Australia. This was at the back of my mind when I first became a teacher, to go and live in a regional area, and that’s the thing that strikes me the most in terms of the literary depictions of regional areas. Sometimes you don’t have as many publishers based in regional areas, or the publishers themselves are based in highly urban areas, so those are the kind of narratives that they favour.

We also had a feature on the social demonisation of teachers, and someone said they were repeatedly told they “are too smart to be a teacher.” How would you respond had that been said to you?

A friend of mine who is an economics teacher used to ask her students: who is more important socially, a childcare worker or an electrical engineer? They would all say ‘electrical engineer’, but my friend would say, a childcare worker is looking after your child who is actually more important. I would strongly disagree with that original comment because we want our brightest minds teaching the next generation. I recently ran into a student at this event and I was trying to remember, where do I know her from? We eventually figured out that I taught her about six or seven years ago. Other than your own family, the people who most impact your life tend to be your teachers.

Given that you studied medical science and neuroscience, and now you write, what would you say to students who are encouraged to embark on a career path that is strictly creative or scientific/mathematical?

People can get directed towards one path or are told they’re supposed to stick to one area or domain. This is something we have to dismiss. I think science and literature/the arts are very similar, they’re both very creative and tackle situations of uncertainty. I believe if you have a different background in addition to the art, that is going to help your creative practices.

Yumna, the author

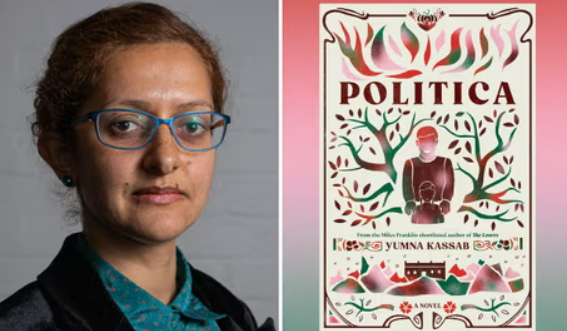

Congratulations on your fourth novel Politica (2024). I had to wait in a very long queue when reserving it from my local library. Here, you delve into the complexity of relationships and family against the backdrop of war, dispossession, revolution and resistance.

As someone with a very specific background who grew up after September 11, there was a lot of vilification and dehumanising of Arabs and Muslims, which is something we need to state very openly. In terms of what we’re seeing in Palestine and across the Middle East, it’s part of a long-term and ongoing project that dehumanises and carries out great violence against a group of people with the full support of political and educational establishments who see nothing wrong with that. It’s not just the othering of a group of people, it goes beyond that. One of the things that has been a big interest for me in the last few years is Latin America; the politics and the history of that region and how there is a parallel with the Arab world. I remember having a chat with a friend from Uruguay and I asked this question, which in retrospect seemed very naive: How did you get rid of your dictators and we’re stuck with ours? Since then I’ve shifted away from that question because it is a very simplistic way to look at the world. One of the things that I find very interesting with Politica in particular is that I was very, very careful not to name countries and places in that book. Some people do say that it’s vague but in hindsight when I consider what’s actually happening in the Middle East and what has been happening for many decades, there’s a certain connotation in relation to Arabs and Muslims when we’re talking about resistance or prior revolutions. I wanted to avoid that and just present the story. But the characters are all Arabs, they’re all Arab names. I just wanted to allow people to make up their own minds. There are a lot of references to the geography of Lebanon, and I do think that these particular stories could actually happen only in one place in the world. When I was writing those stories — and the same with The House of Youssef (2019) Australiana (2022) and The Lovers (2022) — mentally, they’re all set in a very specific place. I do take liberties but if people do know the area and the history, they’re going to read it with an additional layer of understanding.

You wrote this line in Politica: “Politics is all words. Remember, the truth is somewhere else.” At the risk of being trite, where is the truth?

I wasn’t sure when I wrote that, and I’m a gazillion times more unsure now. In terms of political institutions and their whole structures, there has not only been an eye-opening loss of faith. It’s been disappointing and heartbreaking that the mechanisms you expect to stand for fairness and justice have just been abandoned. So I actually don’t know. I’m probably even more uncertain about where the truth is at the moment, or if there’s much truth at all in politics. The question is very open, so I don’t think there will ever be one solid answer. Joan Didion did say that she’d never believe that meaning, in terms of life, could be found in politics. It’s been especially shocking in democratic countries, where you elect these officials and expect them to represent you.

A common pattern across your writing is this non-linear or polyphonic storytelling, where you jump forwards and backwards in time, as well as between sets of characters and perspectives before it all comes together. The way I can describe it as a literary maze that folds into itself. How did you pitch that to publishers and did you ever feel pressured to distil your style of writing?

Most publishers want a linear story and it’s one of the things that keeps coming up in all literary conversations. There is this prejudice towards a story about a character; this is what happens to them and then it ends. That is the parameter of a novel. I don’t think you can actually tell the story of a community with one person. That resonates with capitalism, to just always be focusing on the individual and not looking at how things interact. I’m always interested in terms of drawing connections and certain publishers are probably okay with this style, and others less so. I remember when I was speaking to Ultimo Press, who published Australiana, The Lovers, and Politica, I was saying if the expectation is that at some point that I’m going to sit and write this traditional and commercial linear story, it’s not really going to happen. I might still write that at some point, but I don’t think it’s likely to happen. It’s been a very cool partnership with Ultimo and also Giramondo, my first publisher. People are being trained to think linearly, but it’s probably not natural. I sometimes refer to my thoughts as an ecosystem, because I’m looking at the interconnections between things.

My introduction to your writing was House of Youssef (2019), and as a Lebanese immigrant, I really found it to be an evocative short story collection. Is there a form of writing that you are eager to try, but have yet to?

There isn’t anything that stands out, but at some point, I’d love to do a poetry collection. I’ll probably combine it with something else — Australiana and Politica both have poems in them. I do often say to people that I would like to write a vampire story because I have this long obsession with vampires or the gothic and fantasy genres of fiction.

Yumna, the Lebanese Australian

As you’ve mentioned you are of Lebanese heritage, and lived in Lebanon for two years. How would you describe those two years, and in what unexpected ways have they impacted you?

One of the best decisions my parents ever made was taking us to live in Lebanon. I can’t even measure what an impact that has had on my life; from the way I think, to having access to different landscapes and ways of being in the world. I don’t think I’d actually be the same person. There is this Argentine writer, Jorge Luis Borges, who has this essay called The Argentine Writer and Tradition. He makes this argument that for people who exist in two worlds, a hybrid is created in terms of their thinking. When I think about my writing, I’m referencing two systems. Just speaking two languages, you’re split already. So the thoughts I have in Arabic are very different to thoughts I have in English. Sometimes I’ll be like, maybe I’m complaining too much, now I’m going to exclusively exist in Arabic for the next day. I was reading an interview with this Chinese sci-fi writer — not the guy who did Three Body Problem [Liu Cixin], but his translator [Ken Liu]. He was saying that many people who speak a different language at home go to university, and build this whole vocabulary of their major in their second language. What was so interesting is that he noted that these students don’t have that vocabulary in their original language.

Every Lebanese person has civil war lore or stories to tell, even if they did not live it. What do you think about the narrativisation of the civil war, and how this lack of a shared history continues to plague Lebanon?

I think history is something we write. It’s almost a story that is made up and if we have enough people we go, this is what happened in history. But that’s actually not true. I was conscious of this with Politica. Obviously I’m referencing a war, but I’m also conscious because war history’s presence and legacy is still with us. To say that the war ended is a bit false, even in terms of the situation in Lebanon today, which is very dire on many fronts. It does have a relationship to history, you can’t separate it from its history. There is a reference in the book that we’re all signing declarations, we’re all shaking hands now, and we’ve butchered each other in the past, everything’s fantastic.That is fake. In terms of other countries, maybe things are peaceful, but the history is still present. Same with Australia, we’re not actually done with that. In Palestine, in terms of the future, there’s a lot of violence, all these massacres, the genocide. To actually reckon with that, you do need a very long period of peace. It’s a very long process, and there’s no textbook to follow. For Lebanon, it’s not just under the surface, it’s always there even if you’re not directly referring to it. The past has set up the present and because the past hasn’t been dealt with, neither is the situation in the present, so you can’t even deal with the past. We’re talking about a deep historical trauma at play here.

You were born and raised in Parramatta and have always spoken proudly about your connection to Western Sydney. Is there a piece of fiction or nonfiction about WS or Parramatta that spoke to you?

I really loved Down the Hume (2017) by Peter Polites. It was about class and representing a way of life that hasn’t always been written about. A lot of stuff that is written about Sydney involves share houses and Bondi Beach. This book was not like that. I really loved The Magpie Wing (2021) by Max Easton which is set in Western Sydney. He’s got this storyline about someone who wants Western Sydney to be separate from the rest of the country, as in the ‘Western Sydney separatists’ which I thought was hilarious. Sydney Review of Books has a lot of good essays too.

In late 2023, you were named Parramatta’s first Laureate in Literature — an impressive achievement. Can you give us a sneak peek at one aspect of Parramatta you have begun exploring in your “dictionary of Parramatta”?

I’ve made this list of places that I’d like to explore across this year as I write this dictionary. Sometimes if something is always there, you just assume it’s there and you’ll get to it. The other day I went to this cemetery in North Parramatta which has been there since the early 1800s. I’ve got my favourite places and I don’t tend to venture beyond them. I’ll be driving to work and every single day I’ll see the exact same group of people, at the exact same set of lights, at the exact same time. I’m trying to move away from that. But how do you even write a dictionary about a city? It’s going to be a very personal dictionary, so it’s going to be about my own memories and things that stand out for me. I’m taking it in an expansive way. It could also be about books that I’ve read here.

Rapid fire questions:

Most recent book you read and would recommend – Girl, Woman, Other by Bernadine Evaristo

An author whose body of work you hope to read in its entirety – Alexis Wright. She’s a treasure and I feel lucky to be alive at the same time as her.

An author that is on the rise and you are keen to follow their career – Mykaela Saunders, Hossein Asgari

Parramatta Eels or Western Sydney Wanderers? Western Sydney Wanderers [The discussion segued into our shared dislike of the Manly Sea-Eagles and the Melbourne Storm, and if I’m related to Matilda’s player, Alex Chidiac].

Favourite spot in Parramatta – Parramatta Square and Parramatta Park

Favourite place in Lebanon – Hallab (Arabic sweet place) in Tripoli

A motivational reminder for Honi readers (asking for myself as well) –

It is a cliche to say to people ‘do things that interest you’ but I do say that to my students and I also believe it. Try to stay interested in things and to not lose hope, which I think is a bit difficult at the moment. It’s something I struggle a lot with, but there are good things in the world so keep focused on those, especially at the present time. Never has this been more true.