The recent election for undergraduate Senate fellow was marred by allegations of misconduct against campaigners for the victor Colin Whitchurch and second-placed Francis Tamer. Although numerous complaints were raised with Returning Officer, David Pacey, no action was taken. A Supreme Court challenge to this decision remains a realistic possibility.

The Senate is the University’s supreme governing body, controlling finance and high-level education policy direction. Because voting for its one undergraduate ‘fellow’ is done online, campaigning is less visible, making electoral conduct far more difficult to scrutinise.

The two highest placing candidates exclusively relied on approaching students with laptops to receive votes. Neither publicly declared any policy stances, or launched Facebook pages.

Throughout the election, campaigners were seen filling in ballots for students and looking over their shoulders as they voted. Such actions appear inconsistent with the by-laws, and guidelines distributed to candidates.

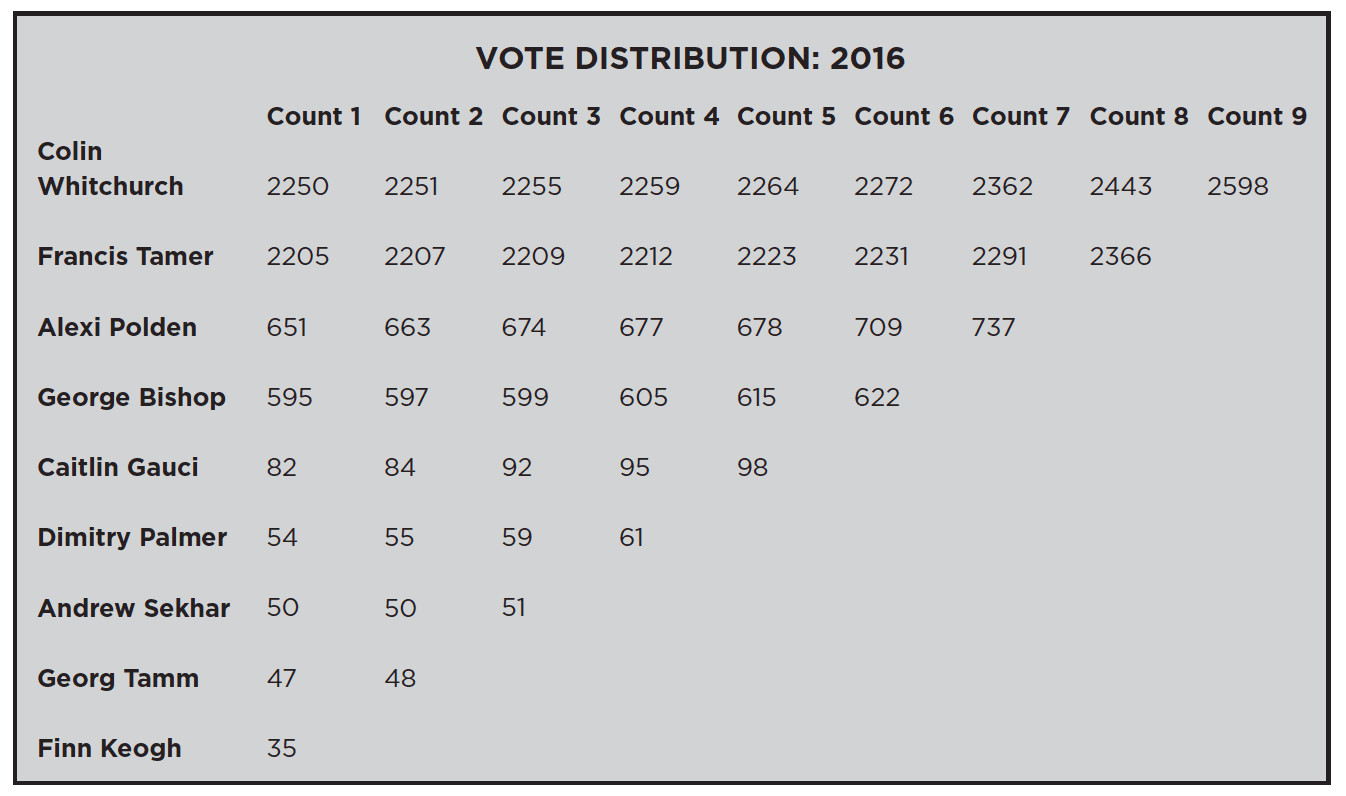

The effectiveness of such a strategy is, however, undeniable. Whitchurch and Tamer amassed 2,598 and 2,366 votes respectively, more than three times the 737 received by third placed Alexi Polden. While this indicates that huge numbers of students voted for them, very few preferences flowed their way as each candidate was excluded from the count. The enormous disparity between first and second preferences suggests that the results do not reflect the actual preferences of the student body.

Unlike other student elections, the Senate race is governed by state legislation, the University of Sydney By-Law 1999 (NSW). A candidate may therefore claim that the election was administered in breach of that statute, and that Pacey could not declare Whitchurch (and consequently Tamer) the victor. The only candidate with ‘standing’ to challenge the decision is likely to be Polden.

The appeal would apply administrative law, the area of law which regulates government action. An affected party would seek ‘judicial review’ of a decision made by a government authority (ie. when exercising a power granted by legislation).

According to section 34(1) of the by-laws, “an election must be conducted by secret ballot”. As “secret ballot” is undefined, the court would focus on determining the term’s correct meaning, and whether Pacey’s conception was too lenient.

The court may decide that section 34(1) was breached, and therefore that the Returning Officer is incapable of declaring Whitchurch the victor.

A secondary line of attack could focus on section 16(1A), which requires that the Returning Officer “is to take all reasonable steps to ensure the fairness and integrity of the election process”. A challenger could argue that Pacey’s response to Whitchurch and Tamer’s actions failed to fulfil this requirement.

If the court were satisfied that Pacey incorrectly applied the by-laws, it could impose a number of discretionary remedies. The court could quash or set aside Pacey’s original decision. Alternatively, it could make a declaration, as to the true meaning of the relevant by-laws, and whether Pacey failed to act consistently with them. Although a declaration is technically unenforceable, it is highly likely that it will be respected.

Finally, if the court felt that Pacey had not complied with 16(1A), it could order a remedy compelling him to perform actions to ensure fairness and integrity.

Importantly, the court can choose not to apply these remedies, even if the candidate can identify how the law has been broken. The court may consider the inconvenience of re-running an election when framing their order.

Polden has not indicated to Honi whether he intends to challenge the election. Going to court is not a decision to be taken lightly. Even the cheapest solicitors and barristers charge several hundred dollars per hour. A senior barrister can charge thousands for each hour.

If a challenge is unsuccessful, the possibility of a costs order remains a significant issue. A costs order means the losing party may be ordered to pay the victor’s legal costs. Such an order, and its extent, is made at the court’s discretion. For example, costs may be reduced where the losing party has succeeded in winning some of the contentious issues at trial.

Bankrupting a student challenging the integrity of an election would undoubtedly be a PR catastrophe for the University, so they’re unlikely to pursue the money. However, it remains a real deterrent. For reference, see the USU Board’s decision to pursue legal costs from former Vice-President Tom Raue in 2014.

Although it is yet to materialise, the prospect of a legal challenge has haunted past senate elections. In 2014, Dalton Fogarty, employing similar tactics to Whitchurch and Tamer won twice as many votes as incumbent fellow Patrick Massarani. Massarani, and third-placed Annabel Osborne repeatedly complained to the Returning Officer about Fogarty’s actions. According to Osborne, the Returning Officer was “infuriatingly hands-off” in responding to these allegations.

While this year, the only formal voting information is the preference flow and final figures, in 2014, scrutineers for each candidate were able to see a print out of each individual vote, coded by reference to the candidate. Scrutineers could see streams of votes for individual candidates – in particular, for Fogarty. The pattern suggests votes were not accrued organically from students seeking to participate, but from campaigners moving through study spaces soliciting votes.

This points to a difficult hurdle for a challenger. The success of the challenge would hinge on the evidence available. Polden would likely need evidence that taints a sufficient proportion of the winning margin. Since the gap is nearly 2,000 votes, this is quite demanding. It would depend on the ability to receive evidence such as CCTV footage of study areas that were targeted, or affidavit evidence from affected students.

This would certainly compete with testimony that all campaigning was legitimate. In comment to Honi, Tamer previously said that he had “full faith in the integrity” of his campaigners, dismissing allegations, as “nothing more than attempted character assassination” against his campaigner.

Osborne and Massarani had begun organising a legal challenge in 2014. They had informal legal advice indicating theirs was a good case, and were in contact with Senior Counsel willing to represent them pro bono. Affidavit evidence, previously submitted to the Returning Officer, was collated. Ultimately, the prospect of a protracted legal battle with the University was enough for the challenge not to eventuate.

Returning Officers have, in the past, been far more proactive in enforcing the by-laws. In 2011, following widespread use of laptops, and allegations that Massarani, then on the other side of the regulations had hosted a barbecue to woo potential voters, the election was nullified. A fresh election was held, which Massarani lost. Following this, the then-returning officer Dr William Adams created the guidelines, which are distributed to candidates. These guidelines, clearly intended to curb laptop campaigning, instruct candidates and their campaigners not to harass, intimidate, coerce or induce students to vote, or assist them with logging in.

This history indicates a problematic inconsistency in the Senate’s application of the by-laws. It is unclear why some forms of inducement are condemned, whilst subtler, more pernicious methods of coercion are deemed acceptable. Moreover, the introduction of the guidelines following the 2011 election has caused other problems.

In the past two elections, the Returning Officer has responded to misconduct allegations by referring candidates to the guidelines. However, unlike the by-laws, they have no legal force. The power to disqualify candidates remains entirely at the Returning Officer’s discretion. The guidelines therefore provide the façade of regulation, without clarifying any ambiguity surrounding the application of the by-laws.

At the very least, a court challenge would provide some certainty over the exact meaning of the relevant provisions, paving the way for fairer, more transparent future elections. The threat of future litigation may also compel the University to draft clearer regulations. A challenge is an undeniable risk, but may well be necessary to clarify and protect the integrity of this and future elections.