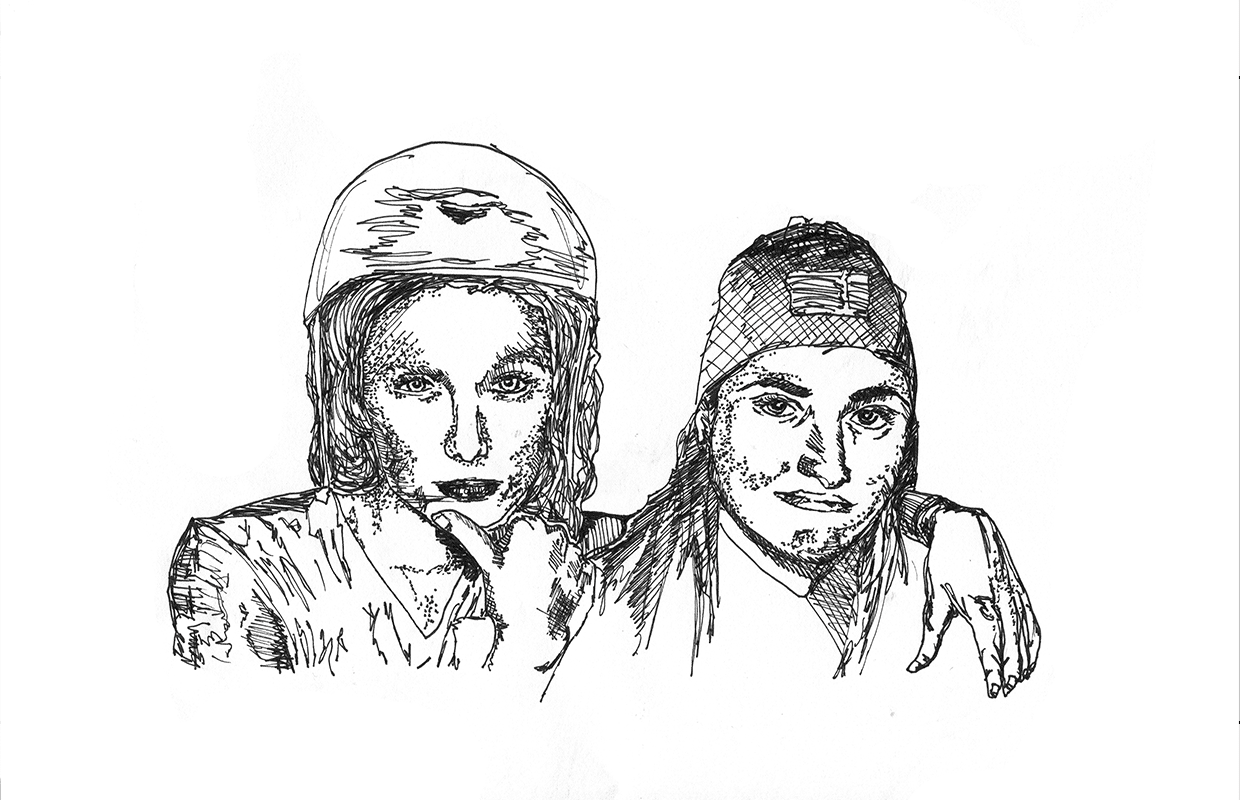

Victoria Zerbst and Jenna Owen are founding members of the Sydney-based, all-women sketch comedy group Freudian Nip. The group started out similarly to many comedians and content creators — by wandering through the USyd performance scene and putting on a show at Sydney Fringe Festival. Since their inaugural show in 2014, Nip has continued to carve out opportunities and hit home runs: Zerbst and Owen have have appeared on the weekly ABC2 night-time talk show Aaron Chen Tonight, worked on projects for Fox 8’s The Slot, and recently the team landed $10,000 in ABC Fresh Blood funding. We caught up with them to talk creating, performing, and taking control of your own trajectory in what is at best a challenging and difficult media landscape.

HS: In terms of forging career pathways, how do you feel creating content in comedy differs from say being an actor or writer?

JO: There’s a greater vulnerability in comedy I feel, and exposing that vulnerability is often really rewarded, which can be a toxic cycle to get yourself in to sometimes, in these heightened versions of ourselves, we do this vulnerable stuff on stage and we get rewarded. People find it funny because it’s real and it’s honest but also normally you can put this vulnerability into writing and you can save face, or you can put it into acting and it’s not your words — but with comedy it’s both.

VZ: It can be quite confronting but it also gives you more power and control over what you say, which is really cool.

JO: Which is something that both of us love too much, probably.

HS: Do you think that comedy is a place that can be called a meritocracy, where hard work has a visible relationship to success, or conversely to that, how much do think other elements play into the situation?

JO: I would say nothing is a meritocracy. In terms of race and gender and class and etc. I would say when we started, we had a big platform and that was the fact that we went to Sydney university and as much as I think we have done a lot and I’m proud of what we have done I would never say that we necessarily ‘deserve’ what we’ve gotten like we also like had a huge advantage.

Maybe two years, or three years I would have said, ‘I deserve this or that’, but like even in terms of an essay I’m currently writing about this… I went to a public school, like in that public school I worked really hard, and got a scholarship, and then meant I went to Sydney university. If I hadn’t have worked really hard and got that scholarship, I wouldn’t have gone to Sydney university, but the reason I could work really hard is because I didn’t have to get a job, like a lot of my other friends had to, because my parents said I didn’t have too, they didn’t make me pay rent or anything while I lived at home, my parents always said that you know, education was important and it should be a priority, not everyone’s parents say that.

When I was younger, like you can trace it back, privilege just gets traced back again and again, when I was really young, my mum stayed home with me. Not everyone’s parents stayed home, so I just learnt and learnt and learnt and all that stuff adds up, all that like little bit of privilege adds up to a lot of privilege, and like, sure I went to a public school, but it was a public selective. All this stuff kind of combines, so if someone was like, do you think you deserve everything you’ve gotten I would say: I’ve done well with what I had, is basically the answer to that question. I think we’ve done really well with what we had.

VZ: We’ve worked hard with the opportunities we have been given, and like working hard is like, less than 50%. And we are aware of that, like a lot of it is just you know, right place, right time, finding the right people.

HS: In terms of creative collaboration, what for you are the elements of being a long term collaboration? As people that are working together all the time, you have to be able to maintain your cohesion. How do you do that?

VZ: We definitely are very thoughtful about like, longevity and also communication. Technically in terms of Freudian Nip, Jenna and I are the co-founders and we work with Geraldine Viswanathan and Jess Bush and they are Freudian Nip as well. We wrote this big agreement, almost like a social contract which kind of fleshes out how we communicate, what we expect from each other, and it all written down, we’ve looked at it and it’s a ten page Google doc. Like its quite intense, we are quite thoughtful with how we communicate with that kinda stuff. We were literally writing and projecting like how we work on set, what are the ways in which we deal with conflict, there’s definitely a forward thinking about how you communicate. For me and Jenna as well I think its different because we do so much together, and its just having meet ups and check ins to discuss, what do we want to work on next, what are our priorities. We also do, I think the healthy thing is we do a lot of other stuff separately.

JO: Because we have different voices. They are obviously very strong when they comes together but they are strong by themselves as well. I feel like we’ve got to a place now, obviously we were friends with Jess and Geraldine before we were friends who did any comedy together. But we have got to a really healthy place where it is I would say almost sisterly, where if there’s a problem that’s just, raised, immediately. We constantly have discussions, we constantly have check ins.

VZ: The whole thing is a continuum of learning.

JO: I don’t know if you agree with this, but I’ve been thinking about it lately. I think sometimes, there is just this horrible dialogue that women don’t work well together. People say that they fight or they don’t do well. I think that women perform the opposite, to combat that dialogue. Then they work so harmoniously together that it’s — not that it’s fake, I don’t think that at all — but they work so hard at being harmonious with each other that sometimes the best work may not emerge. I think that harmony and making people feel comfortable is the most important thing in the world. Vic and I certainly had that but because we put so much pressure on each other and it’s really nice to get to that point where you’re just kind of like “well, fuck harmony, if I don’t like this idea then I don’t like it I’m going to say that right now”.

VZ: I think underlying it is a mutual respect and also a respect for each other’s opinions, and also respect for each other’s skills and contributions.

JO: The place that we are at I certainly wasn’t at before we were together. You have to build women up, you have to build people up to get them to that place where they can say bye to harmony — which is kind of where we are now. So If I criticise an idea of Vic’s or if I say no, and she says no to me, it does shatter this entire thing that I’ve been trying to do. You get to a threshold and you pass that threshold and you’re like “well, now everything you say is not personal and it’s not an attack on me”.

HS: How do you deal as a unit, or as individuals, with people you encounter along the way at all these different levels of creating content who are in a positions of power, and who may be a bit problematic or hold different views to you?

JO: I think we have learnt in the last eight months, that, as well as being self aware, we also have the right to be, strong, argumentative, and assertive about what we want from a project. Just because someone is giving you money, it doesn’t mean you have to conform or consolidate your voice. That’s something again that women do a lot because of the opportunities that we have been denied in the past — everything is an opportunity and they’re expected to consolidate their voice into this one unanimous kind of corporate voice of ‘women speaking’ and it being ‘women’s comedy.’ Something we have fought against when we worked on a couple of different things, is when people maybe want from us (because they have seen our Junkee videos) this political feminist voice. They want this ‘voice of women’ and they want us to be telling them about how badly women are treated in society or, you know, being empowered women or whatever. But asking women to perform feminism like that, as a brand, is not at all empowering.

VZ: Sometimes we wanna write a sketch that’s really dumb. It feels weird to be like: “no, we won’t give a big feminist message for you’” but it’s also like “well no, we are more than that”.

JO: Feminism is agency. And that’s our agency. That we get to decide when we give that message.

VZ: There’s definitely a lot of puppet syndrome, a lot of creators use women as like: “oh this is our feminist voice” —

JO: Or “we’ve got this guy that makes rape jokes but we’ve got Freudian Nip so” –

VZ: “It balances out”. It’s knowing that’s how a lot of people see us —

JO: Because when they are like “oh give us your feminist voice”, it’s not authentic. It’s not taking our voice seriously; it’s taking it as a marketing tool and that’s when we will reject doing that voice. Women should never be told what voice to give to a comedic performance. Because men aren’t told that. No one tells Hamish Blake he needs to be more of a larrikin, or a bit more ‘Hamish Blake’. So why would we be told to be more authentic to our feminist voice?

VZ: It’s really hard to navigate; moments where you actually should be taking on criticism and learning from people, because this thing is we are quite young and new, and we are working with, a lot of the time, men in power who are so knowledgeable, and can teach us a lot. It’s just knowing when to cut out the bullshit. You have to really think about it a lot. It’s hard. Half the time you want to learn new stuff, and then half the time you want to not feel patronised, or like you are giving too much because you’re a woman.

HS: What do you feel about the nature of success as a concept, do you think it is something people should be chasing all the time, what is success for you?

VZ: I think a lot about that. I think success is something, I mean it sounds really trite but I think success is something you have to define for yourself. You have to set up your own values and your own systems and question intensely the structures of success that are laid out to you as ‘musts’. Before I started doing comedy I thought success was doing arts law at Usyd. I was gonna work as a consultant for one of the big firms in management consulting. I equated success with external outcomes that I subscribed to that I didn’t define for myself and I thought that was what success was. I think you definitely have to define what success means for you, and that is informed by your values. And this is a massive privilege to even think about what matters to me and ‘what should I do’. A lot of people are just surviving and doing what they need to do. If people have the agency and autonomy to decide what they want to do I think a lot of that is figuring out their values.

If I were to have a career that would make me quite comfortable and happy in Australia where I can write the shows I want to do and work with inspiring people, that, to me, would be more in keeping with my values, then you know, making it big and making sacrifices so you live in a world that is really, I don’t know, morally repugnant. Or that is based on insidious power structures or dynamics that wouldn’t make me feel happy as a person. So it’s a series of trade offs. For me, my value is always going to be the work. Actually making stuff that I can imagine other people watching and feeling inspired by and thinking about. And not even knowing what the result of that is like there are so many works that I look at and I think ‘fuck im so glad that exists in the world’ and that’s the kind of stuff I’d like to make and that’s what motivates me more than anything. And I’ll cop other shit so I have the opportunity to make that kind of stuff, but for me, my value of success is a body of work that I can look back on and think, I’m so glad that exists.