Last year, I volunteered for the University of Sydney’s (USyd) LINK program, which connects low socio-economic (low-SES), regional, and First Nations high school students with tertiary education opportunities. On one day, I was giving a campus tour of USyd to students from Chifley College, a school in Mt Druitt, Western Sydney

Its enrolment comprises 80% of students who come from low socioeconomic backgrounds, and 17% First Nations students.

The boys had been jovial throughout the tour. When we were opposite the Law Lawns, the group stopped me. A few nudged each other, and one spoke up.

“Where are all the people who look like us?”

I was immediately embarrassed and surprised. Had he noticed, based on our measly 30 minute tour, that USyd’s First Nations enrolment amounted to less than 1%?

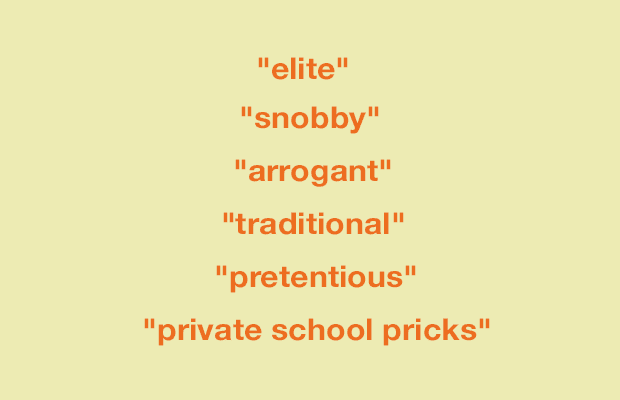

It is undeniable that USyd has a reputation for being uppity. In an online survey taken by current HSC students, USyd’s reputation oscillates between “good” and “snobby”. The term “elitism” appears ten times, “pretentious” three times, and “conservative/traditional” seven times.

A student from a school in Parramatta described USyd as full of “private school pricks,” one from Bardwell Park associated it with “arrogant people.” A student from Seaforth acutely summarised the default critique: “I have heard it is not an ideal university as it is where people go to show off their wealth” and “[is] marketed to people with a higher income/standard especially those attending private schools.”

Private school students primarily labelled USyd a ”prestigious” University. This label is contentious considering how many low-SES students criticised USyd for only servicing high-status students.

Statistically, USyd has above average numbers of high-SES students, whilst below average numbers of low-SES students. Dr Melissa Hardie, Associate Dean for the Faculty of Arts and Social Science, and Dr Kieryn McKay, Project Manager of LINK, argue that “[USyd] has historically been the preserve of an elite body of students, largely derived from private schools and Sydney’s selective schools.”

The rumors that USyd was a high-SES haven were verified in the 2008 Bradley Review. This federal investigation into higher education found that Group of Eight (Go8) universities such as USyd were under-representing low-SES, regional, and First Nations students. The Report recommended governmental intervention to raise the proportion of low-SES students by 20% for 2020.

Despite this, government funding for programs which enhance low-SES students’ participation in tertiary education such as LINK was reduced under the Abbott Liberal government in 2013.

Since the report, universities have only made slow improvements. In 2016, USyd’s student body was made up of only 7.36% of low-SES students and 7.15% of regional students.

The highest withdrawal rates are among First Nations students, mature age students, regional students and followed by low-SES students. It begs the question: why do the most underrepresented demographics drop out?

The Bradley Review admitted more research is required to explain why certain minority groups fail to complete their studies. One explanation may be the idea of “sociocultural incongruity,” where low-SES students are exposed to discourses and norms of tertiary education which are incongruous with what is familiar or comfortable.

In other words, when minorities mix with the blue-blooded culture on campus, they curdle.

Environmental factors do tend to favor high-SES students. Teachers often presume that conditions common to private and selective school students, such as supportive home environments and social well-being, also apply to low-SES students, and conduct their classes with these things in mind. In doing this, they rarely centralise minorities’ needs, as it can upset the majority and disrupt productivity.

Low-SES and high-SES students are also socialised differently. Both are subject to similar academic obstacles––NAPLAN, for example. However, financial advantage differentiates their scores. Through private tutoring, the purchasing of additional textbooks, quiet study spaces and shorter commutes to places of education, the high-SES student has a better chance at academic success. Studies have argued that although private school students are accustomed to privileging University over work, many low-SES students cannot and their performance suffers as a result.

High-SES students struggle to recognise that through the lens of a boy from Chifley, USyd is white and privileged.

There is a need for better retention programs, more funding for outreach programs and more volunteers willing to exit their bubble and assist programs like LINK. More must be done to erase cultures of class-based oppression.