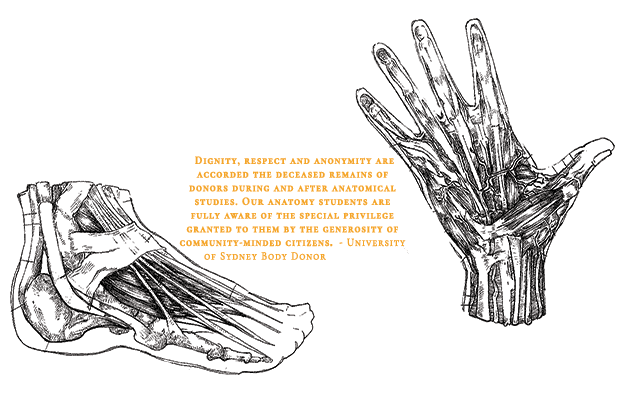

“Dignity, respect and anonymity are accorded the deceased remains of donors during and after anatomical studies. Our anatomy students are fully aware of the special privilege granted to them by the generosity of community-minded citizens.” – University of Sydney Body Donor Program.

Under the sandstone edifices, the long avenue’s and flourished archways; beneath the libraries, lecture halls and grassy knolls of the University of Sydney (USyd), there lies a mortuary that collects and stores the bodies of countless donors. Morgues themselves are cold and stark, and the air inside these donation rooms are still and peaceful with a mood that is deeply bittersweet. The smell that wafts across the room and into the dissection labs is not of human flesh, but of formaldehyde. These bodies are meant to be there, their previous inhabitants wished it so. As they await their dissection they lie still in boxes like giant filing cabinets. Above them, students and professors go about their day unaware. There is little public knowledge of how the bodies are transported from Mannings funeral home to the USyd location. There is even less known about the location itself. The process is shrouded in mystery. General opinion suggests the corpses are somewhere unknown beneath the University’s Anderson Stuart Building.

University body donor programs function successfully across the country. There is one at almost every public university in the state. Within each program lies a primary understanding of confidentiality and secrecy by students and teachers that privileges and respects the dead.

Connor Phillips, a medical science student at the University of Technology Sydney, is unaware of where bodies are kept permanently at his university. When students enter the lab the specimens are already sitting there in giant industrial fridges, ready to be dissected. “They never explicitly say that we aren’t to know where they keep the bodies but they never go out of their way to show us either,” he said.

“I would assume that the reason is to minimise the risk of potential misconduct from students who during a lapse of judgement may decide to do something stupid. There’s some weird people out there” he said.

The trials of life are much the same as they are in death: a series of tests of eligibility define the kinds and ages of bodies moving through these university systems. Donations for the USyd body donor program are taken from the Sydney Metropolitan area, which not only means that you have to live there but that you have to have died in the area as well. A series of infectious diseases that prevent a person from donating their bodies are boldenly outlined across the programs website. A set of strict criteria also aid the decision for donors and families who are made aware that the body must be distributed to the university within 24 hours of their death. If a funeral is to be held, the body will not be present at the service due to this tight time frame of transferal. If the individual has been dead for more than 48 hours, if a family objects to donation at the time of death, if a post mortem is conducted, or if the program is at capacity at the time of a donor’s death, the donation can be cancelled.

The labs where the classes take place are established and unchanging to implement certain security measures that are known and repeated by students. “They’re all there to minimise risk to students and the bodies.” said Connor Phillips, a medical science student at the University of Sydney. A student’s first lab requires a safety talk and the signing of an agreement regarding the responsibility of students during their use of the donated bodies.

“Most of the body parts are dissected and prepared by lab technicians due to the limited number of bodies donated to the program. An error by a student in the preparation of a body would remove some of the value of the body as a teaching resource,” said Connor.

In an absurdist way, this hidden morgue, is much the same as most community locations where dead bodies come to rest. Western society is afraid of them. They’re abnormal, strange and affluent dead things that are hidden away, burnt in cremation or buried deep beneath in a cascate that conceals remains from surprise findings that could occur even hundreds of years later.

But university students that benefit from these donor programs approach these bodies with a kind of humble appreciation. “After my first anatomy lab, the biggest consolation or thought that helped me work through my feelings was the absolute privilege we have as medical students, that people have donated their bodies to help us learn and to ultimately help others in the future” said Indianna Chant, a medicine student at the University of New South Wales.

Whilst there’s a first time for everything,but dissecting a donated human body is, for most, unlike anything else.. The process is reminiscent of a Kazuo Ishiguro book —a stark experience with bodies detached from individual personality. “My first experience with prosected cadavers was more confronting than I was anticipating. I found it difficult to come to terms with how these now chopped up and stripped back body parts were once someone’s loved one,” said Sammy O’Rourke, a medical science student at USyd. “I also felt I wasn’t prepared for what I was going to see but the specimens didn’t look as human as I thought they would.”

From what students have described, it seems the process is a redolent reminder that we are just organs, skin and bones. “The smell of the preservative agent formaldehyde is incredibly overpowering and leaves people quite light headed,” said Connor. “That, coupled with the visceral nature of the bodies, was a lot to deal with but it wasn’t until after the class that I felt the impact of it.”

“In the class you’re very curious and excited as it’s a rare opportunity to have. But once you leave the room it changes the perspective. Needless to say that I skipped a few meals after the lab that day.”