Along with ever-increasing materialism and scientific veneration, the word “dogma” has taken on a pejorative edge. Where identifiable, an incontrovertible truth simply means an unprovable truth, and an unprovable truth is no truth at all.

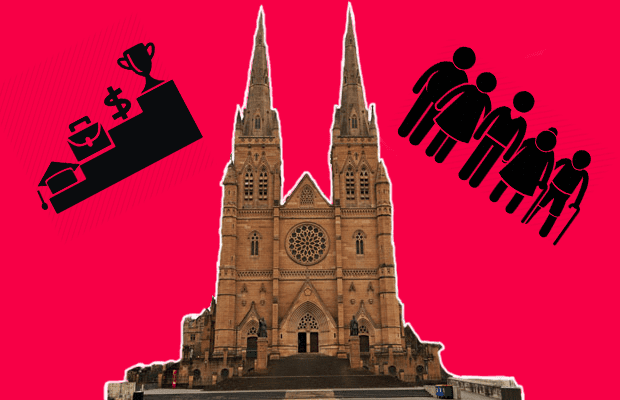

Society imagines a binary between rational secularism and irrational religion. But in reality, even those who don’t follow a religion live their lives aspiring to overarching social narratives, like the ‘family breadwinner’ or ‘first in the family university student.’ In many ways, these narratives are very similar in form to religious dogma.

Religion involves more than being a supplicant for a deity. At its core, it serves as the highest actionable force. From religion flows the dogma upon which meaning and motivation is moored. A “god,” or some force approximating and supplanting one, provides the endpoint of an otherwise infinite regress of meaning — entrenching a foundation from which the evaluation of importance is made simple and predictable.

On the flipside, atheistic ideas have championed rationality and autonomy, seeking verifiable knowledge and freedom from an overarching teleology. “God is dead,” and the actioning force of religion, at first glance, is conspicuously absent. Atheism may imply an absence of faith, but even the secular world is not free from archetypal, quasi-religious stock stories requiring faith and belief. These stories are promulgated, constantly iterated as they are taught to the next generation. When rigidly applied and accepted as dogmatic truth, these stories result in prescriptive ideas of success and career paths.

Social stock stories are born as reflections of a broader cultural fabric, and consequently become self-evident.

In a Western, middle-class context, there is almost transcendent aspiration, materially underpinned by capitalist desires for wealth generation and ideologically entrenched through the liberal value of the individual based in work and merit.

Societal narratives revere those able to create the highest levels of personal advancement, forging concrete tales of expectation and desirability, like the unspoken expectation that each generation moves up from the social or economic station of the preceding. This fundamental expectation becomes the yardstick of what is worthwhile and is carried down through each generation; value is placed on things like education, hard work and income, and the specific means of achieving each are promoted and enforced within families. These tales take on a life of their own by becoming common to specific groups in society.

Take the suburban nature of many middle-class families. To the uninitiated, the appearance of monotonous repetition from each household leaves little room for unique individuality. These commonalities range from similar houses, general family structures, and similar employment prospects and incomes. When parents pursue the subconscious desire to abrogate this conformed structure to differentiate the self, and fail, the hope for future generations to improve the standard of living pulsates through parental expectations, reframing success along the action-guiding lines of education. Desires for further education are prompted and departure from the previous generation’s shortcomings are promoted. The stock story of the “first-in-family” university student is created.

Once actualised, these stories are only affirmed by intergenerational influence, repeated as time passes and taking on an ever-growing popularity amongst certain communities, these tales lose their artificial nature and are entrenched as dogma. When hearing rags-to-riches tales, or seeing those around fulfilling the narrative and achieving success, the story becomes all the more real; not only is it possible, but it is also desirable to follow it.

The road to success shrinks into a single, tried-and-tested lane which is rigidly enforced. The realisation of stock stories of success imposes strict lessons like the apparent fact that a service-based occupation trumps manual labour — the rule that tertiary education must be undertaken for “success” or that long hours are inevitable when seeking career progression. These decisions may seem autonomous but all are the product of conceptualisations of success rooted in dogma and packaged in common sense. The actualisation of these stories only perpetuates further dogma.

These secular stories exist ad infinitum, guiding every member of society, affirming or rejecting their convictions and actions, in individualised ways.

Society may despise dogma, but it loves a good story.