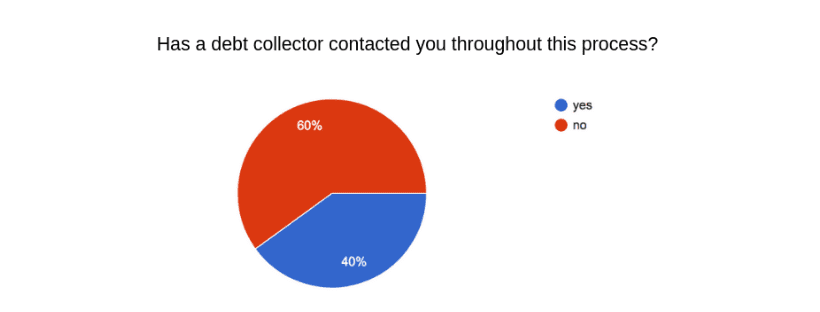

At 8:00am on a Thursday morning a University of Sydney Masters student received a phone call from a private debt collector. “A debt from Centrelink has been passed on to us,” the caller said. “We highly recommend that you start a payment plan with us today or we will have to start charging you interest.” The phone call arrived the morning after a lengthy phone call Meg had conducted with a department representative. Centrelink had confirmed once again that her $2000 debt would be paused for appeal. This was well into the third appeals process she had requested and the third time Centrelink had slightly diminished her debt since a series of false debt letters began arriving in her mailbox in early 2018.

This experience isn’t unusual and it’s not particularly new either. In 2017, the Commonwealth Ombudsman conducted an inquiry into Centrelink’s automated debt allocation system or Online Compliance Intervention (OCI). The investigation revealed a series of flaws in the systems operation and, in turn, outlined a fairly loose set of recommendations to suggest further improvement. Two years on and hundreds of citizens still receive unexplained, vague and false debt letters. Students on youth allowance are amongst the largest demographics most affected by these “robo-debts.”

Meg called the department again. This time it was to get clarification on how on one end, Centrelink was assuring her that her debt was being reassessed and on the other, a debt collector was confirming that a payment plan must begin immediately. “We apologise for this,” said yet another Centrelink representative. “Your debt was paused as a result of its reassessment, but once the reassessment time limit has ended (a period of 3 months) our system automatically unpauses the debt and passes it on to a debt to a collector.”

Since the government first introduced the automated system, thousands of debt letters are sent out weekly to citizens on welfare and youth allowance. It is widely considered (by the Australian Unemployed Workers Union (AUWU) in particular,) that up to 90% of these assumed debts turn out to be false. Fees can span anywhere between six hundred and three thousand dollars and they are all reasoned under Centrelink’s claims of “overpayment while on youth allowance.” The debts are diminished gradually but rarely halted, and if they are, it is always due to frustratingly long processes of contestation from the individuals falsely assigned this debt.

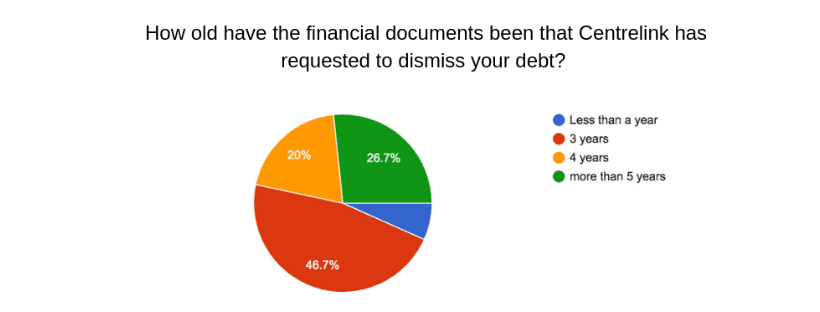

It is on the onus of the individual affected to respond and prove the system wrong. The problem is, in the case of welfare recipients, many are overworked, living without an occupation or surviving without a roof over their head. Students under youth allowance are away from home, studying full time and trying to look after themselves. If these individuals are unable to revise payslips and other documentation asked of Centrelink from up to seven years old, the organisation will simply continue to charge interest on that person’s debt. Ironically, Centrelink auto cull’s all letters from MyGov after a period of twenty four months. As a result, Centrelink can never offer much aid to those searching for their own documentation and there is no guarantee that they can be accessed by Freedom of Information (FOI) or any legal department. The process sees organisation #notmydebt, continue to encourage individuals on welfare to retain all financial documentation in the likely advent that they are sent a debt letter in the coming months.

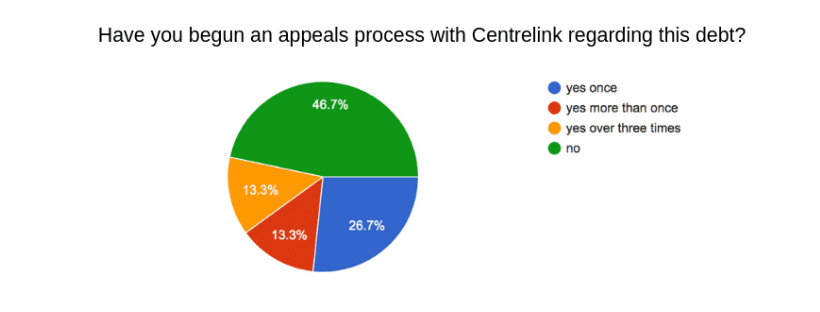

Honi conducted an anonymous survey collecting the opinions of recipients on Centrelink welfare payments from a series of online forums including Not for profit organisation #notmydebt’s private Facebook group. It was perhaps unsurprising to find that 53.3% of these recipients were under 35 and 40% were between the ages of 26-30. 73.3% of recipients said they were on youth allowance when they started receiving debt letters. 100% of these letters were confirmed to be under claims of ‘overpayment.’ It is understandable, that in the online forums of Facebook and Twitter, a higher demographic of young people engaged with Honi’s survey. But it is also perhaps fair to outline that in the case of students on youth allowance, particularly those from rural areas living on or around campus, are amongst some of the most vulnerable within this system. 73% of students surveyed admitted that they had no awareness of their own responsibility to follow up with Centrelink and prove their debt as false, while 46.7% revealed they had not begun a process of appeal with the organisation even after more than half of those surveyed had been dealing with robodebts for up to 2 years.

The various ways individuals experience and deal with their false Centrelink debts comes down to a range of societal and personal factors. Meg, outrightly refuses to pay her false debt. “They [Centrelink] claim that when I first moved from home to Sydney to study at University I wasn’t correctly reporting my income. They’re talking about a period from January to February when I first moved to Sydney. But I didn’t have a Centrelink account so how could I be reporting anything,” she said. “They clearly assume that the money I was making while on my gap year was the money I was making while starting University. Which is not the case. It’s obviously a flaw in the system and I’m not paying it.” Meg moved to Sydney with savings and support from her parents. She is also able to get advice and ongoing support from family and friends regarding this debt. For many, this is not the case.

In Honi’s survey 53.3% of individuals stated that they had paid a debt that they still believe to be false. An anonymous general comment said “I just started paying back the debt, even though I [still] think it’s wrong because I didn’t know what else to do. I’m $2000 through a $4000 payment and it’s nearly killing me (and I don’t mean that in a problematic metaphorical way — I mean literally financial stress is incredibly triggering for me).” An anonymous comment Honi received in the early release of the survey simply states “it seemed legitimate at the time.” Various other recipients are simply exhausted by the system. One said, “Fortunately, I was in a financial position where paying off the debt was a smaller price to pay compared to the mental and emotional cost of fighting a welfare system designed to tire you out through attrition.” Regarding these varied ‘reverse onus processes’, a spokesperson from the organisation #notmydebt told Honi “I find the deliberate abuse of the trust and ignorance of vulnerable and disadvantaged people [by Centrelink] to be totally abhorrent.”

Since the Ombudsman’s Inquiry, Centrelink requests that those owing funds ask for a review of the debt from within 28 days of receiving a debt letter. Students do not receive calls from Centrelink directly, assumably as a result of an understaffed system that simply does not have the funds or resources to give any further care to its recipients. The system leaves little room for human error, over crowded student schedules or casual indifference to the debts. In a statement to Honi Centrelink said “Anyone who has received a letter regarding a debt can call us on the phone number on their letter if they have any questions or require further assistance.” In a follow up correspondence with Centrelink Honi was told “Our priority is always to any customers who are experiencing issues. We would genuinely like to help them. If the students you mentioned have already called our department and have additional concerns, we can arrange for them to be contacted by a staff member to follow-up further.” Centrelink denied any further comment on the specifics of the robo-debt system.

The OCI system itself was hastily introduced by the Coalition government in 2016. It was a fairly rushed procedure with little consultation with the organisation and its workers. Unions were not contacted and the implementation clearly left room for substantial error, error felt exponentially across the professional sector, citizens on welfare and union representatives. The Public Service Association of NSW (PSA) told Honi “Mandatory staffing caps provided by the coalition government really impact Centrelink’s ability to run productively. These automated systems were not developed with the workers in mind and they were not developed with the recipients of welfare in mind either, they said. “This kind of work needs to be done by real people with a focus and knowledge of the support needed [by recipients] for this kind of work. An automated system simply cannot provide this.”

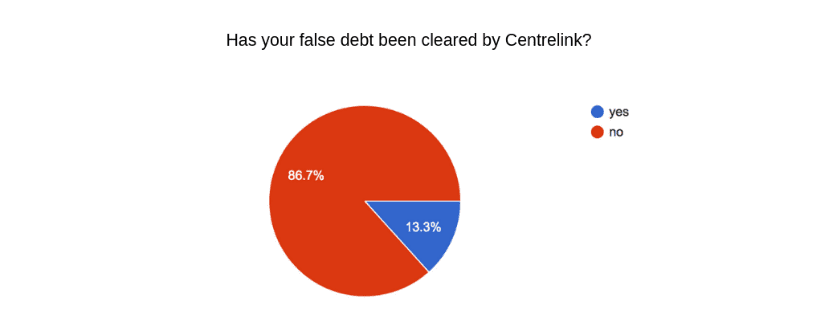

The emergence of such a system is primarily a result of serious staffing cuts to the sector, which is a view shared by the AUWU and PSA. 5000 Centrelink staff have been sacked over the last 5 years and in lieu, Centrelink has been unable to keep up with the demand for its services.“My debt with Centrelink has gone through a number of stages of reassessment and appeal, and the debt has been reduced multiple times over the past 8 months,” Meg explains. “Every time the debt gets reassessed, I ask the customer service representative what the original reason for the debt is, and they can never give me a logical answer.” A vast majority of students suffering with these debt letters share similar stories. 86.7% of individuals surveyed by Honi say they have not had their debt cleared by Centrelink, while 60% of those surveyed were contacted by debt collectors at least once. 80% of respondents had called Centrelink to argue their debt several times.

For so many it seems an end is never really in sight. In March of this year The Saturday Paper wrote a piece on the incredibly damaging pressure that the robo-debt process brings to those on welfare. The piece outlined that Greens senator Rachel Siewert told an estimates hearing she had received notice of “at least five people that have taken their own lives directly related to having received correspondence related to online compliance.” Centrelink ensures on their website that ‘if [individuals] are not happy with the outcome of the review, [they can] either make a complaint to the commonwealth ombudsman or appeal through the court.” But it is this process of dissection and the particularly harrowing stress of financial burden in the first place that really highlights the problematic elements of these automated systems and the way Centrelink representatives are trained to operate regarding these systems. On top of all this, individuals are simply looking for the reasoning behind why their debts have arisen, a central point that so many Centrelink representatives simply cannot answer. “I have provided them with all the documentation they asked for such as pay slips and separation certificates, and every time I do, I continue to ask what the reason for the original debt was, with no response,” said Meg.

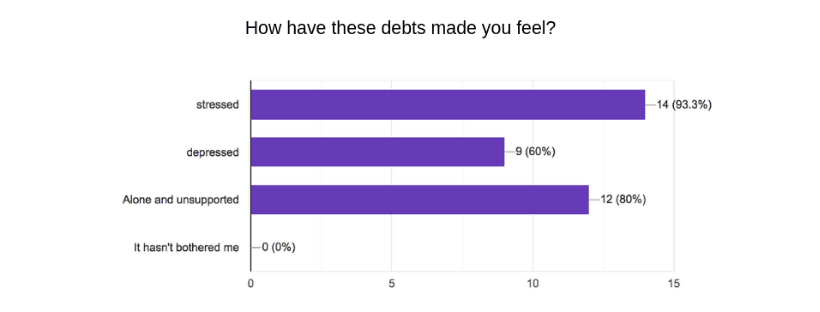

The findings of The Saturday Paper piece shares similarities with the feelings of those still involved in Centrelink debt disputes. Of those surveyed, 93.3% said the letters made them feel stressed, 80% said the debt made them feel alone and unsupported and 60% said the process made them feel depressed. Those surveyed also described their experiences with these debts as leaving “them feeling helpless”, and causing “a lot of unnecessary anxiety and stress.”

Meg said she’s cried over the phone to Centrelink representatives because it’s just so frustrating. “By the time you get to speak to someone, the person on the phone can only tell you what’s on the screen in front of them and usually passes you on to someone else. It’s mentally and emotionally exhausting,” she said. “I always reported my income accurately and accepted the fact that centrelink would no longer support me when I started my Masters. So to receive a huge debt of almost $2000, and for absolutely no one to be able to give me a reason as to why I was receiving the debt, made me angry,” she said.

Meg said she’s cried over the phone to Centrelink representatives because it’s just so frustrating. “By the time you get to speak to someone, the person on the phone can only tell you what’s on the screen in front of them and usually passes you on to someone else. It’s mentally and emotionally exhausting,” she said. “I always reported my income accurately and accepted the fact that centrelink would no longer support me when I started my Masters. So to receive a huge debt of almost $2000, and for absolutely no one to be able to give me a reason as to why I was receiving the debt, made me angry,” she said.

Honi reached out to the University of Sydney for comment, to which they said, “we are able to provide supporting documentation for any student who wishes to challenge incorrect information being held by Centrelink in relation to their enrolment.”

“This can include providing a letter confirming enrolment details for a previous year, or students can access a certificate of current enrolment via Sydney Student at any time,” they said. “We encourage any students distressed by these letters to contact our student support services or CAPS for assistance.” Of the students Honi talked to, many did not even consider contacting student services as they see their Centrelink responsibilities as detached from their university enrolment, study and counselling services available. This is unfortunate, as the Student Representative Council (SRC) caseworkers are particularly knowledgeable on the operations and issues associated with Centrelink’s “brick wall.”

There is a wider discussion to be had on the worldwide issues of online automated debt systems. In early 2017 the United Nations (UN) also included in its ICESCR final submission an outline of the effect of the debts on everyday Australians. It is believed that the UN looks to investigate this issue globally in the years to come. Thus, it seems absurd that in a society where major corporations regularly tax evade, a government organisation continues to falsely prosecute some of our most vulnerable citizens. An automated system cannot understand personal context, emotional suffering, abuse or student mental health. It doesn’t recognise a delayed appeals process almost halted by overcrowded Centrelink phone lines. Individuals need the human responses of a well-trained representative to be authorising and confirming these debts. The system cannot continue to function as an organiser of welfare recipients owings, until it fixes its series of fatal flaws.