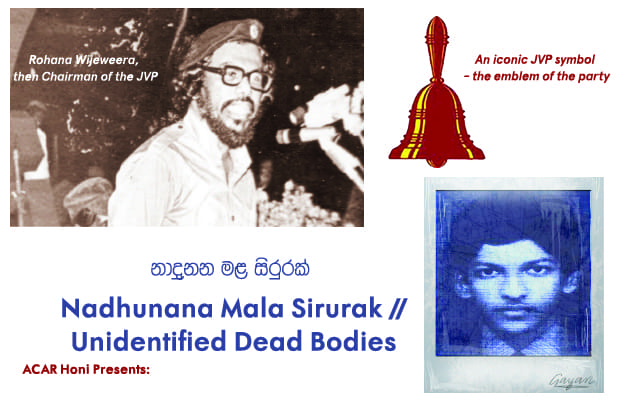

In the mad rush of August 2008, when the final preparations for our move from Colombo to Sydney were being made, an envelope of photographs fell into my hands. I recognised most of them to be duplicates of photographs in our family albums. Mixed in with the duplicates and discards was a set of photographs from the mid-1980s and 1990s that I had never seen before. Among them was a photograph of Gayan — an original print of the version used in his ‘missing student report’. I didn’t know who he was at the time; I assumed he was a relative I hadn’t met, someone from the extended family; in a way, I suppose he was.

I kept the photographs in a box with me throughout high school and early university. I would lay them out on the floor of my bedroom and go through them from time to time. I’d study the faces, the poses, the architecture, the greenery, the art on the walls — some of which I recognized, some of which I didn’t. During one of these routine examinations, I learnt from Amma that the young man in the worn 2’ x 2’ photograph was Gayan, a friend of hers who was killed in 1989.

I have learned most of what I now know about the politics and the people of the People’s Liberation Front (JVP) revolt of 1989 from Amma and Thaththa – from listening to their conversations with each other and with friends from their university days. Whenever they gather, there invariably comes a point when they mull over that time of their lives and reminisce about the comrades they lost.

The student movement and the JVP

The student movement in Sri Lanka’s South became a powerful force over the 1980s. Its ranks swelled, in large part, because it was left to students to mobilise opposition to the increasingly dictatorial tendencies of the United National Party (UNP) government. There was a lot of overlap – in terms of membership, ideology and activities – between the student movement and the JVP, the largest grassroots Communist party in the country.

Both movements were rooted in the island’s poor and largely rural masses. Indeed, most students and JVPers came from such backgrounds. If it were not for access to free public education, it is unlikely that many of them would have been able to access secondary schooling and university studies. In the decade preceding the JVP insurgency of 1989, it was this segment of society that bore the brunt of the UNP’s free-market policies.

The origins of the JVP

Prior to this era, the country’s poor masses had largely mobilised around the ‘Old Left’ and its typically urban, elite and English-speaking leadership. Parties such as the Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP) and the Communist Party of Sri Lanka (CP) had come to lead Sri Lanka’s growing labour movement in the early 20th century and continued to dominate this arena of politics in the decades immediately following independence. Alongside the post-independence labour movement occurred a long-awaited Sinhala and Tamil cultural revival, with which emerged self-directed platforms for expressing and propagating the aspirations of ‘ordinary’ people.

The island’s system of free primary, secondary and tertiary education no doubt contributed to this; while wealth and social power remained concentrated among the urban elite, education had ceased to be a commodity that could only be purchased by them. Beginning with the People’s Liberation Front (JVP) which was founded in 1965, the ‘New Left’ emerged in the South of the island from this atmosphere of national pride, self-leadership and autonomy. The JVP launched its first insurrection in April 1971, against Sirimavo Bandaranaike’s Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) government. This attempt to establish socialist rule on the island was crushed by the government within a few months.

The lead-up to 1989

Following seven years of increasing economic hardship and racial disharmony under Sirimavo Bandaranaike’s SLFP government, the UNP secured a parliamentary majority at the general election of 1977. This is widely regarded as the starting point for the despotism, corruption and militarisation that have come to be so deeply entrenched in life on the island. In conversation with Amma and Thaththa, it’s clear that this is what their experiences lead them to believe.

In February, 1978, within about six months of becoming Prime Minister, UNP leader J. R. Jayawardene transferred the Parliament’s state powers to an Executive Presidency and assumed this position himself. He did so without holding a presidential election. In 1979, the Prevention of Terrorism Provisional Act was introduced on the pretext that it was necessary for fighting the growing militancy of the Tamil separatist struggle in the North of the island. These laws could be invoked once a ‘State of Emergency’ was declared under the Public Ordinance Act. Significantly, they did not grant the presumption of innocence for parties accused under the Act. Nearly a decade later, these laws were brought into force in the South of the island during the crackdown on the JVP insurgency.

The union movement which had traditionally led the fight against economic oppression was left in shambles following the defeat of its General Strike in 1980. In an unforeseen and unprecedented response, the UNP government summarily dismissed all 130,000 public servants who were striking in protest of the rapidly rising cost of living. Heading into the strike, the unions were continuing a well-established tradition of strike action – no previous strike had ended in complete defeat. The UNP government’s response dealt a heavy blow to the tradition of union organising and strike action on the island. It was a very discouraging sign for workers and effectively severed the connection between the Old Left and the country’s poor masses. The UNP government had set out to demonstrate that mass action was a futile effort and, in large part, it succeeded.

In 1981, the government issued a document of policy proposals. titled ‘Education – Proposals for Reform’ (colloquially known as the ‘White Paper’), which outlined its plan for privatising the free public education system. Over the following year, the Socialist Student Union (SSU), the JVP’s youth wing, led a sustained and ultimately successful opposition campaign against the proposed reforms. In addition to university students, this campaign mobilised many high school students and members of the general public as well.

In July 1983, a wave of anti-Tamil pogroms shook Colombo, Sri Lanka’s capital, and other parts of the island’s South. This led to an escalation of operations by Tamil militant groups who were fighting for an independent Tamil homeland in the North and East of the island. The government’s ongoing counter-insurgency in the North and East intensified, as did its crackdown on left-wing, anti-government activities in the South. The JVP and elected university elected university Student Councils , along with a number of other left-wing political parties, were proscribed in 1983 on the pretext of the State of Emergency that had been declared earlier that year. While the other proscriptions were subsequently lifted, the JVP and Student Councils remained proscribed.

In 1984, prompted by the deaths of two university students at the hands of the police, university students began establishing Action Committees within their universities. The Action Committees filled the void of organised student leadership and representation that had been left by the proscription of Student Councils. The Inter University Student Federation (IUSF), which had existed in various forms since in the 1970s, also rose to prominence during this time and would go on to play a central role in the insurrection of 1989. From 1984 onwards, it took on a highly organised structure that was composed of representatives from each university’s Action Committee. In an environment that was becoming increasingly hostile to political dissidence, the IUSF provided a much-needed platform for university students across the South to organise collectively. It is worth noting that the IUSF was largely populated by students from the SSU.

Both Amma and Thaththa entered the arena of left-wing political activity through the student movement. As a high-schooler, in 1982, Thaththa became heavily involved in the White Paper fight. Amma very clearly identifies the PMC fight of 1987 – the student movement’s next major campaign – as the turning point for her, as it was for many others of that generation. This was a particularly crucial moment in the broader socio-political landscape of the island as it directly fed into the JVP insurrection.

The North Colombo Medical College (PMC) was established as a pay-to-enter private medical school which was to award the same degree qualification as the island’s leading public medical school, the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Colombo. In 1987, medical students at the University of Colombo collectively boycotted their exams in protest of this. The boycott effectively brought the public medical education system to a halt, and by extension, stalled the private medical college as well. For Amma, the realisation of just how powerless those of little wealth and status were rendered in the face of the well-connected was borne out of this struggle to guard free public education.

This campaign unfolded in an environment of public outrage about the government’s decision to enter the Indo-Lanka Peace Accord. The Accord, which was formalised in July 1987, was an agreement between the Indian and Sri Lankan governments that aimed to quell Tamil militancy in the North. It involved devolution of power to the North and East of the island, withdrawal of Sri Lankan troops from these regions, voluntary disarmament of Tamil militant groups and the presence of an Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF) to oversee the process. Many Sinhalese viewed the Accord as a concession to the demand for an independent Tamil state and a violation of Sri Lanka’s autonomy.

These events fueled growing discontent among ordinary Sri Lankans about the political repression, economic inequality and corruption that characterised the UNP’s governance. Capitalising on the UNP government’s soaring unpopularity, the JVP was able to mobilise widespread socialist and patriotic fervour across the South.

In this sense, 1987 was a turning point in Sri Lanka’s political landscape. It was during this period that the JVP’s armed wing, the Patriotic People’s Movement (DJV), launched its operations. University students in the IUSF and SSU increasingly entered grassroots political organising, taking up responsibilities beyond the scope of student politics. All public universities across the South were gradually shut down by the government to control the burgeoning uprising.

The insurrection of 1989

The militancy of the JVP, which gave impetus to the democratic political mobilisation that was proliferating across the South, ultimately culminated in a full-blown Marxist-Leninist insurrection. Tens of thousands of people rose up against the prevailing political and economic tyranny with the hope of establishing a more compassionate, equal and just socialist state in its place. The UNP government responded with a brutal counter-insurgency that was carried out by the Sri Lankan Armed Forces.

Between the years of 1987 – 1991, over 60,000 people were killed or ‘disappeared’ by Sri Lankan Armed Forces and pro-government paramilitary groups in Sri Lanka’s South. This violence was targeted at JVPiers and JVP-sympathisers, at times in situations where people were merely suspected of being involved with the JVP. By March – April 1990, all but one of the JVP’s politburo had been killed or disappeared. Most of its membership was also wiped out. The insurrection had been defeated. Thaththa, who was deeply embedded in the JVP’s ranks, left the island for France in mid-1991 to avoid being killed and to continue the JVP’s reorganisation effort from abroad. Amma left for France in 1992 to join him there.

Amma and Thaththa had met through Students for Human Rights (SHR), an organisation that documented the abductions, killings and disappearances that were taking place under the UNP government’s watch and smuggled this information out of the country to raise international awareness about the situation. Gayan, the young man in the photograph I found, had been the General Secretary of Students for Human Rights and was also a representative of the IUSF; someone both Amma and Thaththa worked very closely with. He was abducted and disappeared by army personnel in December 1989.

Unidentified dead bodies were a common sight in the streets and canals of Southern Sri Lanka in those days – often naked and battered; sometimes limbless or decapitated; sometimes burning on rubber tyres. Amma recalls coming across the administrative term ‘unidentified dead bodies’, or ‘නාඳුනන මළ සිරුරු’, for the first time while working for Students for Human Rights in late 1988. She had been handed a single sheet of grid paper upon which was a list of locations where unidentified bodies had been seen and further information about how many bodies there were and what conditions they were in – burnt, burnt with tyres, burnt beyond recognition and so on. This data, along with records of missing school students, university students and other civilians was collated and filed by SHR. Amma still has a small portion of these files with her. However, most of the larger collection was misplaced in the aftermath of the insurrection’s defeat.

Remembering 1989

My parents broke their ties with the JVP in the mid-1990s due to disagreement regarding its stance on the Sri Lankan government’s war against the Tamils in the North and East. Thaththa remains very critical of of the JVP’s hypocrisy and Sinhala chauvinism when it comes to the issue of Tamil self-determination in Sri Lanka. Talking to him about this, I sense a great deal of regret about how regressive the JVP has come to be in this sense –– “It’s like any other Sri Lankan political party. Well, of course, they talk about globalisation and workers rights. But at the same time, when it comes to the mother of all problems in the country, the National Question, they shy away from it.”

As far as I understand, however, Thaththa’s main qualm with the present-day JVP is its failure to do justice by those who were killed and disappeared in the insurrection of 1989 –– “They’re so scared of that past – that militancy, that revolutionary spirit… They fear that the past will come to the fore if you talk about the people who were disappeared. Their mission is to forget that past. And to a large extent they have.” The Party has proven to be resolutely unwilling to persist after meaningful redress for the dead and disappeared in the three decades that have elapsed since the insurrection. In this sense, it does very little to counteract Sri Lanka’s ‘official’ state narrative which seeks to erase the collective memory of 1989.

Now and again it strikes me that the insurrection of 1989 really did end in total and utter defeat. The critical mass of the rebellion was taken out. Between the two of them, Amma and Thaththa mourn many, many dear friends and comrades. I have often wondered whether a society can truly recover from such a collective ordeal. There is something vacuous about being born of this generation — a generation whose collective bravery and idealism was a force to be reckoned with; a material and ideological threat so significant that the government set its troops on them. But this legacy also inspires me endlessly. The gratitude I feel for all those who answered the JVP’s revolutionary cry for a just and equal society is ineffable. Their story is one that I take immense pride in sharing.

සමාජ දේශපාලන අරගලයන් හි දිවිදුන් සියලුම මිනිසුන් ට උපහාරයක් වේවා!

Editor’s Note: At 11:15pm on 30 November 2021, this article was updated at the author’s request to more accurately reflect the details and depth of the narrative.