There’s a recurring line in the song ‘Michelle Pfeiffer’ by Mahawam that the artist hurls out of their mouth, a bullet speeding towards skin: “but imminent death / but imminent death / but imminent death / but imminent death”. I first heard the song walking home one night in late June. As I listened to it, I thought of the way death hangs over people of colour, real yet abstract; always potential.

Months later, I discovered that the song was written in response to the artist’s HIV diagnosis. As a nonbinary Black person, Mahawam – born Malik Mays – seeks to explore the proximity to death experienced by queer black people. For me, this clarified a truth internally known, of the inextricable link between being a person of colour and being a queer person in a world hostile towards both.

Both bodies of colour and queer bodies fundamentally disrupt the fantasy of white national space. Anthropologist Ghassan Hage argues in White Nation that in Australia, whiteness as a project seeks to maintain control over imaginary borders, under the guise of multiculturalism and “the discourse of tolerance”. In challenging the reproduction of this fantasy, queerness and ethnic otherness exist as threat, and come under danger. First Nations feminist academic and activist Aileen Moreton-Robinson conceptualises this danger as the over-definition of the racial other’s body, against a disembodied, invisible whiteness.

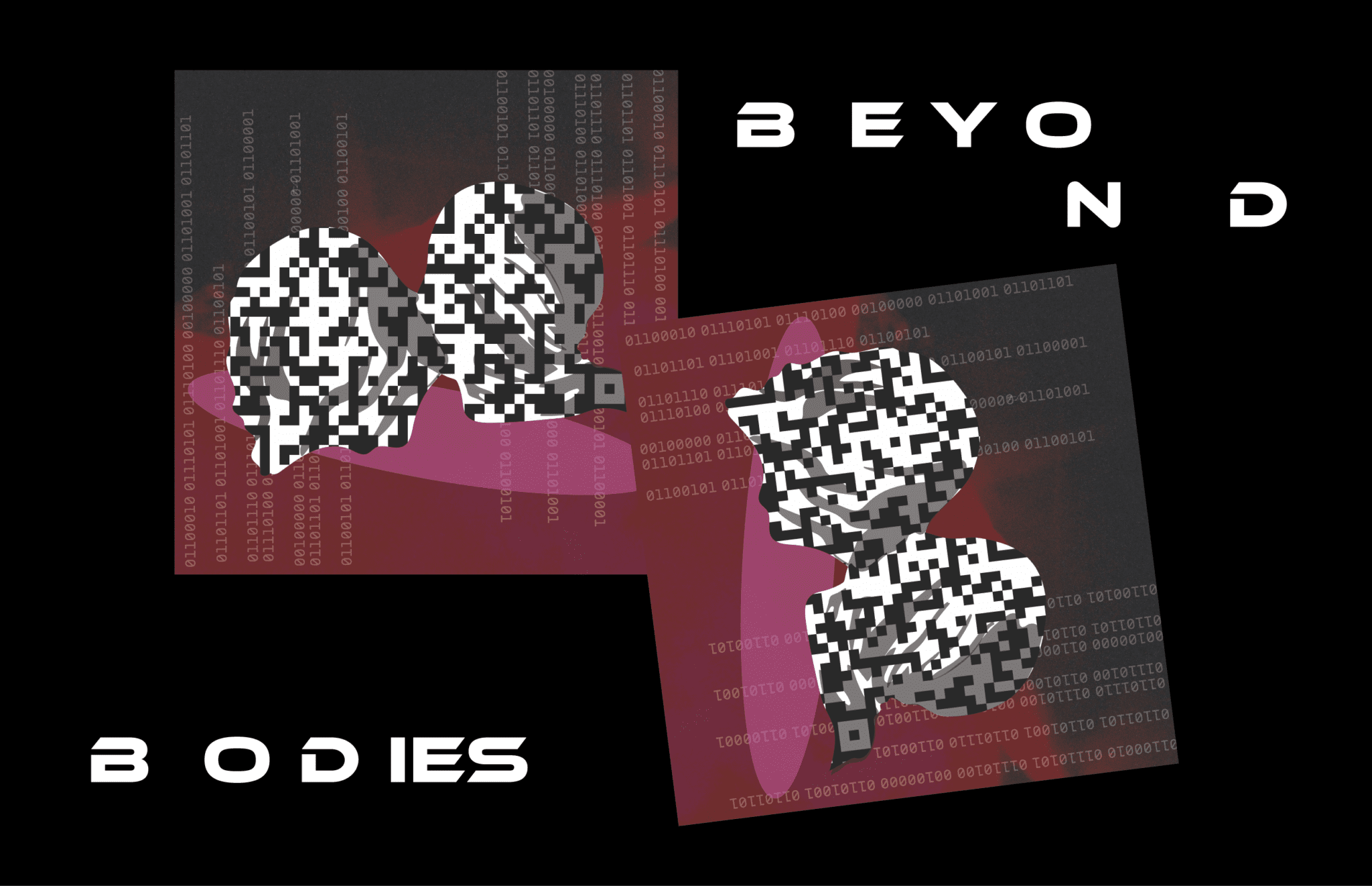

This violent foregrounding of physicality extends to queer bodies; like bodies of colour, they function as depositories of death within a cultural imaginary always ready to dispose of them. The bodies of queer people and people of colour are never promised. In a liminal space ever-heavy with the potential of physical bodies ending, can selves be created beyond physicality?

The concept of queer futurity as explored by José Esteban Muñoz becomes radical here, reflecting the hybridity and synergy of queer people of colour. In Cruising Utopia, Muñoz suggests that queer space is one of utopic promise, existing beyond the physicality of the present: “queerness exists for us as an ideality [… it is] the rejection of a here and now and an insistence on potentiality or concrete possibility for another world.”

Muñoz’s vision of futurity is embodied by Sydney and Adelaide-based band Collarbones in their album of the same name, taken from Muñoz’s work. In an interview with the music site Pilerats, vocalist Marcus Whale reflected on ‘futurity’ as “this imaginary space to which I return when I try to unpack my romantic instincts.” The album explores what Whale terms “that most future-oriented form of longing – the crush”. Queer futurity as presented by Collarbones is never removed from bodies. Rather, theoretical concepts and experiences co-exist as limbs tangled in the dark.

This is apparent in the album’s structure. The interlude “Futurity” is a 15-second track of pulsing machinery noises, framed on either side by “Deep” and “Heavy”, pop-leaning dance tracks that distil fears and anticipations about relationships. This linkage between futurities and (potential) queer, bodily intimacy shifts the contradictory nature of desire and uncertainty into a space of momentary meaning-making. “Futurity” opens a space in which bodies transcend physical boundaries through virtual existences. This is intimately tied to the digital age; the queer crush becomes refracted by the specificity of desire and intimacy in the online. In creating a blurry space between reality and fantasy, digital space provides for world-making.

Though radical in disrupting embedded imaginaries, digital potentiality is not without limitations. The work of Essex Hemphill, an African-American poet and activist, complicates digital space as often unsafe. His poem “On the Shores of Cyberspace” weaves the impending destruction of his physical body as an HIV-positive gay man into a questioning of the internet to provide harbour for queer bodies of colour:

“I’m counting T-cells on the shores of cyberspace and

Feeling some despair

[…]

I stand at the threshold of cyberspace and wonder:

Is it possible that I am unwelcome here, too?

Will I be allowed to construct a virtual reality that empowers me?”

Hemphill reminds us that the internet is far from a neutral and apolitical site of utopian creation. Simultaneously, rather than providing a space that surpasses bodies, bodies flow into digital sites. Hemphill’s poem is never divorced from queer bodily intimacy:

“I occupy my lover’s long-fingered hands at the threshold of cyberspace.”

Perhaps, then, digital space allows for contingent world-making; for relief for bodies-under-threat but not for the doing-away-with of physicality. Perhaps an elimination of physical bodies is not desirable; Hemphill and Collarbones chart the joys, along with the pain, of bodies existing together in unsafe spaces.

Digital space remains, for me, a fraught fantasy, one that embodies Muñoz’s vision of “a horizon imbued with potentiality.” Given that all structures are operationalised fantasies, digital space could provide for creating kinder fantasies for marginalised identities.

In “Michelle Pfeiffer” Mays remarks offhandedly, “gold’s been leaking from my lesions lately, it’s crazy”. Maybe this presents the most productive digital potentiality: the gold doesn’t cancel out the lesions, but presents a space of beauty and alternative meaning on the edge of destruction. It was never about going beyond bodies, then. It was about finding and creating those spaces where bodies under threat are able to glow.