I’m not sure if my peers in the Faculty of Science can relate, but I often feel that hours of soul-draining mathematics causes me to need to release my inner artist. I often do so through writing — usually poetry or slice-of-life pieces.

However, only a year ago, I sought to write a fantasy text, which required considerably more stimulus than what I could muster from the real world. I wasn’t sure where to get the inspiration for a world of my own, since fantasy TV, film, and novels are fairly uninteractive. I needed something I could delve into and investigate first-hand. It was then that I realised that an oft-overlooked form of interactive entertainment — tabletop gaming — was precisely what I was looking for.

In other words, I decided to go vampire hunting in my spare time.

Dungeons and Dragons, the game I played, was developed in the 1970s by an aspiring worldbuilder, Gary Gygax. An instant bestseller, D&D entered an entertainment industry dominated by rising digital mediums like film and video games. Fantasy films were ascendant following the release of the Star Wars trilogy, and high fantasy novels were continually being pushed into the mainstream hands of enthralled readers. While these mediums allowed for rich stories to be told, they were restricted by non-interactivity, and the alternative — video games — were restricted considerably by technical limitations that overshadowed any potential for storytelling aside from text adventures.

Amidst the proliferation of all these mediums, one question remained — how could an author tell both a descriptively compelling narrative while also giving the reader an opportunity to participate? This is what many viewers, and even Gygax himself, sought to resolve with role-playing games. D&D not only allows for an author to provide both a narrative and participation to a viewer, but is also the only medium which allows for this experience. The trick? It’s simple — the author takes an active role, rather than a passive one.

Even the most technologically stunning video games of the 21st century, from The Elder Scrolls to Mass Effect, are restricted by one key problem that I call choice oversight — in other words, there’s only so much that an author can predict that a player will want to do. In many games, this can often lead to uneventful conclusions – for example, killing the essential NPCs in The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind causes the “thread of prophecy to be severed” – effectively ending the main questline. Worse still, this can even lead to results that run contrary to the developer’s vision of the game — for example, in Minecraft, due to the limitations of the AI of the villagers, the most efficient way to manage villager trades is to abduct them in boats back to your base, and then repeatedly breed and kill them to gain desirable trades. This paints a dark narrative on an otherwise innocent story of a person trying to survive in an unknown world.

The power of bringing the storyteller into an active role is that it allows for dynamic storytelling. Texts are published at a static point in time, and as such, questions that arise after the date of publication cannot be answered – unless you follow it up. With D&D, questions arise during the process of storytelling. The author can improvise and adapt to the choices made by the protagonists of the story and ultimately curate an experience for the player.

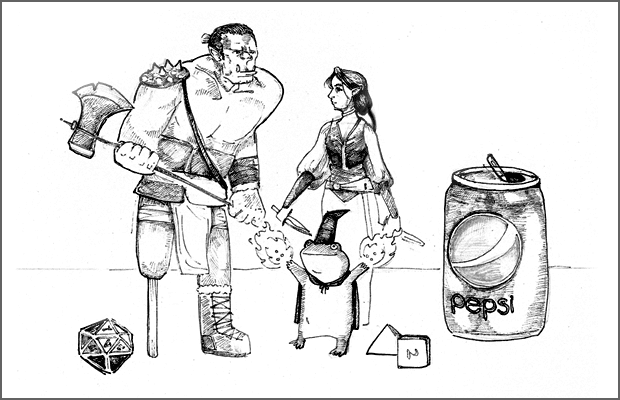

After having slain a great number of vampires, as well as putting on the shoes of a Dungeon Master myself, I have come to find that my writing has improved when attempting to understand the gaze of the reader. More valuable and relevant information finds its way to the spotlight of my pages compared to before, as I have come to learn what my players – my readers – find more interesting. No longer are there bland descriptions of the paintings on the wall . Rather, the odd depiction of Boblin, a tiny (and adorable) goblin, who sips his milkshake in the middle of a dwarven tavern, makes it into print.

Whether you want to be Edward Elric from Fullmetal Alchemist, or simply wonder how long you would survive in a zombie apocalypse, D&D is a great way to explore that, and it doesn’t only fulfill your own fantasies — it also helps the aspiring authors out there who need to playtest their novels.