A few months ago Honi Soit was contacted by a student, concerned about moving plans to implement so-called ‘graduate qualities’ (GQs) into undergraduate students’ final transcripts. It was alarming, to say the least — so we did some digging. Here’s what we found.

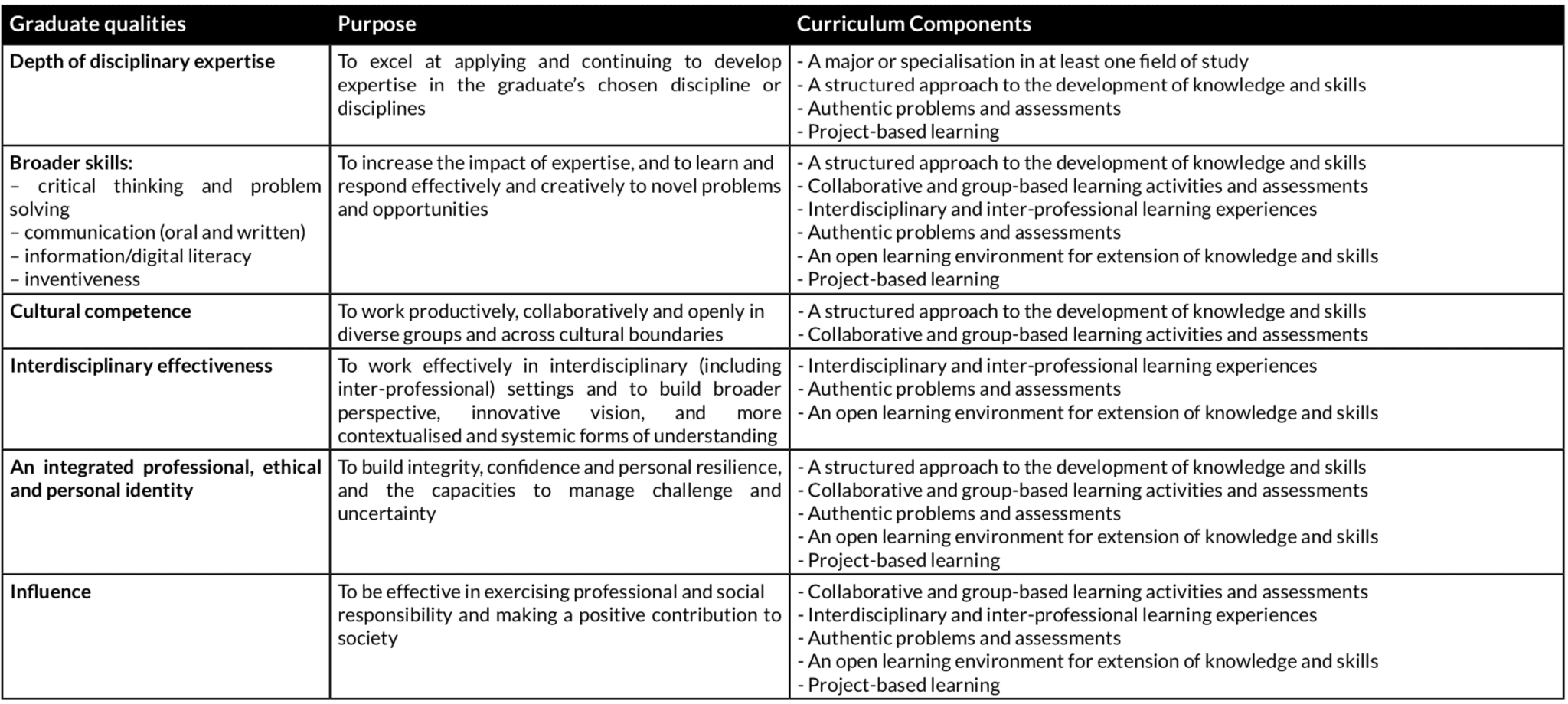

These plans began as far back as the binding Learning and Teaching Policy 2015 which named the acquisition of seven graduate qualities that would be “necessary to contribute effectively to contemporary society.” These seven qualities would remain unchanged in the University Strategic Plan 2016-2020, where GQs are an embedded focus within the plan to transform the current undergraduate curriculum.

The definitions for each attribute were developed by the Assessment Working Group which came out of the Strategic Plan, tasked with developing and delivering the Plan’s specific assessment initiatives. Observable, and potentially able to be assessed, indicators of each of the qualities – known as ‘curriculum components’ — are attached to each of the GQs.

Since 2017, there have been consultations with various, but select, faculty staff and students. In 2018, the Assessment Working Group set up working parties to develop assessment rubrics and design assessment plans for curriculums. In 2019, an Assessment Advisory Committee was created on which the SRC President sits. At the end of this year, faculties will present draft assessment plans to the Assessment Advisory Committee.

Core components within the curriculum framework — such as collaborative learning activities and assessments, interdisciplinary and inter-professional learning experiences — and new degree structures such as the Bachelor of Advanced Studies, have been developed insofar as they map directly onto the implementation of GQs within undergraduate student learning.

In an attempt to avoid standardised testing, the assessment of GQs would be rubric based — mapping student progress — and communicated via feedback in the form of “positive statements” about the abilities of each student, apparently irrelative to their peers and the rest of the cohort. Co-chair Professor Peter McCallum told Honi, via email, that there is no intention “to provide numerical marks or grades to assess student attainment of the graduate qualities.”

It remains unclear exactly when in the semester students would be able to access this feedback. Furthermore, the Assessment Working Group have flagged that they may consider how to assemble and assess evidence for a final statement on a student’s qualities on graduating transcripts.

If a university-wide approach to assessing the adopted GQs is successful, assessment planning shifts from the unit of study to the overall degree curriculum level. In the Assessment Working Group 2017 working paper, approved by the Academic Board, it is noted that, “such an approach has the potential to reduce the overall burden of assessment on students and staff and allow more emphasis to be placed on providing students and staff with feedback.”

However, this still begs the question as to whether the graduate qualities represent something observable within student learning across the length of their degrees. Are these GQs simply metaphors for the oftentimes complex and shifting real experiences of undergraduate study — and is that enough?

While many details of the curriculum overhaul are yet to be confirmed, it is set to be of significant impact for staff and students. At a most basic level, the reforms pursue two ends: bringing units of study in line with a broader university-wide curriculum, and focusing assessments on the skills that USyd thinks are needed in the workforce. Whether the reforms will in fact improve students’ learning experience, however, remains to be seen.

In an age when a university education increasingly feels like a conveyor belt towards the job market beyond, these changes do much more than creating a stronger central curriculum — they move learning away from the pursuit of knowledge and toward the acquisition of professional skills. While McCallum’s email promised that “Faculties may adapt the University wide rubrics to meet the needs or language of a particular discipline,” staff are still expected to uphold the spirit of the rubric. Given a trend of University faculties being asked to capture increasingly diverse disciplines, it is also unclear whether there will be ample flexibility to adapt the rubric.

Given the scale of change being demanded, significant conjecture should be placed on how meaningful the assessment of GQs will be for students. Many of the qualities USyd hope to assess seem difficult to test given their subjective nature. A letter sent to USyd by Jeremy Chan and Madeleine Antrum, the President and Vice President of the Sydney University Law Society, asked whether assessments testing ‘influence’ and ‘inventiveness’ — two of the GQs — could be trusted.

“We do not believe that academic assessment can adequately represent subjective qualities and may misrepresent students from particular backgrounds,” they said.

The core concern of Chan and Antrum’s letter is their belief that the results of GQ assessment will be published on students’ transcripts, alongside existing unit marks, thus being available to all future employers. As already noted, the Assessment Working Group is yet to determine what form assessment will take, or whether these results are published. However, this letter never got a response from the University, perhaps emblematic of the questionable extent of student consultation throughout this process.

In his response to Honi, McCallum claimed that, “In 2019, we will begin a series of student engagements including: (1) a student-facing information website, (2) student news story on the project and ways to contribute, (3) a student forum and information sessions.” It does not appear that any of these have happened yet, and if they are planned to happen next year, the feedback will arrive after draft assessment plans have already been made, perhaps meaning that the policy will be too far along in its creation for meaningful amendment.

While a particularly personalised and private process may avoid some of the problems canvassed, there are reasons to think there is a necessary degree of standardisation to the assessments. The 2017 Working Group paper claims that using a rubric avoids standardised assessments, which it acknowledges would be “burdensome, expensive, and difficult to sustain,” as well as having “unclear” benefits. However, for multiple teachers to be able to track a student’s progress across multiple units, in multiple disciplines, measured against a central list of qualities, the chances of highly-catered feedback likely dwindles.

* * *

Policy development and consultation will continue into 2020 with implementation in 2021. Given the implications these reforms will have for students, and indeed how we define the purpose of tertiary education more broadly, these discussions are certainly worth paying attention to.