The mass hysteria that followed the outbreak of the 2019 novel coronavirus has been met with skepticism and disdain by those in progressive circles. These critics contend that the response to the epidemic has been Sinophobic and orientalist, drawing on Yellow Peril narratives of East Asians as carriers of disease. This legacy has its origins in the colonial conscription of indentured labourers from China who, during industrialisation in the United States, were exploited in the garment and railroad industries. These unhygienic working conditions were ripe for disease, and following outbreaks, Chinese communities were ostracised.

Notably, the environmental causes of illnesses were ignored and the outbreak racialised — Chinese immigrants were seen as disease ridden due to inferior racial make-up. In an article published by Slate, Jane Hu argues that this stereotype remains pervasive in discourse on the Wuhan virus whereby “the Chinese brought the disease upon themselves by eating the ‘weird’ animals where the virus originated.” As news of the outbreak spread, a viral video of a young woman eating a bat with chopsticks was promoted by media outlets like the Daily Mail and RT as the ’cause’ of the Wuhan virus. Contrasting the resulting uproar on Twitter deriding Chinese eating habits to reality provides ample confirmation for Hu’s argument — the video wasn’t set in Wuhan, or China, but rather in the Pacific Island nation of Palau.

While Hu’s article successfully interrogates the racialised narratives that emerged following the outbreak, it has two key limitations. Firstly, it ignores the enormous public health risks posed by commonplace industrial food production in the West. Secondly, in trying to counter Sinophobic rhetoric, this enormous risk is obscured by the author’s misguided attempt to sever the link between meat production and the outbreak, implicitly characterising the epidemic as a highly contingent phenomenon. As evolutionary ecologist Rob Wallace argues in his book Big Farms Make Big Flu, these structural factors cannot be ignored. Not only do capitalist relations of production engender the likelihood of a pandemic, in its current form, they make this threat practically inevitable. This makes orientalist narratives of ‘exotic’ meat consumption being the sole cause of the outbreak particularly sinister as it obfuscates and racialises the destructive potential of ‘mundane,’ Westernised production.

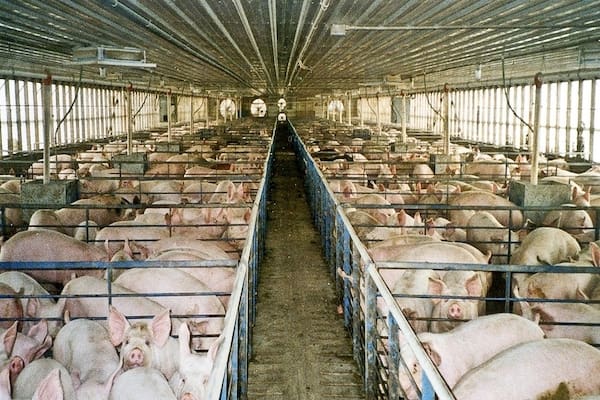

An open letter to the World Health Organisation (WHO) signed by nearly 300 public health experts outlined the countless ways that industrial meat production could be the perfect breeding ground for the next global pandemic. Factory farming – the dominant form of industrial meat production – refers to the large-scale enclosure of animals to mass-produce meat as efficiently as possible. As humans became more prone to deadly outbreaks of pathogens as they congregate tightly in unsanitary cities, factory farms have urbanised animal populations that were previously distributed in small holdings across small-scale farms.

Additionally, the increased risk of disease by large populations of animals in close proximity, as well as the added stress of constant exposure to faecal matter, ammonia and other gases arising from this matter make these creatures far more susceptible to infections. These infections can be, and often are, viral — but factory farming also engenders the threat of antibiotic resistant super-bacteria. Currently, this threat kills 700,000 people a year, with this number expected to rise to 9.5 million by 2050. In the United States (US) and European Union (EU), 75% of antibiotics are used in agriculture, often dangerously and in violation of minimal regulations. Animals are given antibiotics routinely in small doses, a practice that is ineffective in preventing disease, but very likely increases the risk of producing bacteria resistant to treatment. Moreover, since factory farms systematically dump animal waste into local waterways, antibiotic resistant bacteria efficiently spreads into the populated areas.

It would be incorrect to regard this issue as a trade-off between public health and attempts by food producers to efficiently meet the demands of a meat-seeking global population. Rather, it is better characterised as a struggle between a handful of autocratic corporations on one side, and their exploited workers, the health of the global population and a sustainable future for the planet on the other. Corporate agribusiness primarily consists of a handful of state-backed monopolies; 75% of world poultry production is carried out by a handful of multinationals, with this number decreasing. In 1989, 11 companies controlled the breeder’s market for broiler chickens while in 2006 this number came down to 4.

These multinationals perfectly understand the potential of a dangerous pathogen emerging from food production. However, they externalise these costs onto contract farm workers, who often have little to no insurance and require government subsidies to recover from the extreme economic burden a viral outbreak can place. In 2016, the New York Times (NYT) reported that an outbreak of avian flu cost up to $2.6 billion dollars in expected earnings, $400 million in foregone taxes and up to 16,000 jobs. If it weren’t for the minimal government intervention that occured — requiring farmers to slaughter their poultry en masse — the NYT projected that it could have cost up to $40 billion dollars.

Economic cost aside, low-income contract farmers and exploited factory workers are at extreme risk of infection. A 2007 study in Iowa highlighted that rural residents exposed to pigs were 55 times more likely than non-exposed individuals to have contact with the Swine flu. Moreover, these labourers, often from marginalised racial backgrounds, suffer under inhumane working conditions. For example, in 2016, Oxfam revealed that poultry workers at major American corporations were forced to wear diapers while working as they were denied bathroom breaks. The threat of human-animal interaction promulgating a global catastrophe cannot be understated; a 2017 research study by the University of New South Wales highlights that of the 19 influenza strains that have infected humans in the last 100 years, 7 had occurred in the 5 years preceding it, with this rate increasing. The neoliberal mantra is in full swing; socialise the economic burden of ‘free’ enterprise to the taxpayer, privatise the rewards, and externalise the risk of catastrophe to the global population.

As in the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, the environmental causes of disease — state-subsidised corporate greed and poor working conditions — are ignored, and the resulting outbreaks are racialised. Having understood that overt Yellow Peril narratives are too obviously racist for their ‘woke’ reader-base, outlets such as Bloomberg Media in their article ‘Chinese Food Will Determine the Spread of Pandemics’ have opted for red-baiting and Orientalist characterisations of the CCP as foreign despots. Yet these attacks ring hollow when comparing industrial meat production in the West to China. While 95% of EU and US meat production is done via factory farming, 44% of livestock in China in 2010 was still raised traditionally. Furthermore, given that the American health care system has reportedly been discouraging many possibly infected people from seeking medical attention due to financial burden, the idea that ‘Chinese Food’ rather than McDonalds™ has a greater likelihood of determining the spread of pandemics exposes the ideological entrapments of the Western media class. When confronted with the self-destructive impulses of the system that their power rests upon, all they can do is shift the blame to a foreign boogeyman.

Moral considerations aside, the threats caused by industrial meat production cast a dark shadow over the possibility of a thriving, future human population. Like climate change, the dominance of its economic actors in the state-corporate complex seeks to limit the possibilities of our actions. We are consumers in the economic world and spectators in the political — if we want to change the world, we are told to change our consumption and the spectacle. To foster the possibility for political action, we must shift our attention from patterns of consumption to the relations of production and the system that reproduces them.