Sport is central to the Australian social psyche: it speaks to aspirational elements of our national identity both in its egalitarian nature and its capacity to unify us. This summer, Australia was forced to reconcile the extent to which we would accept our sporting heartstrings being pulled by politicians. Prime Minister Morrison’s hope that big sixes and inswinging yorkers would melt away the horrors of the bushfire crisis was roundly rejected. Instead, we have sought solace from the partisan cauldron of politics on the sporting field.

It’s a common refrain whenever athletes speak out on social issues, particularly women or athletes of colour – most famously, “shut up and dribble.” Sport has never been divorced from politics – to suggest otherwise is incredibly naïve, and to suggest that it should be, equally so.

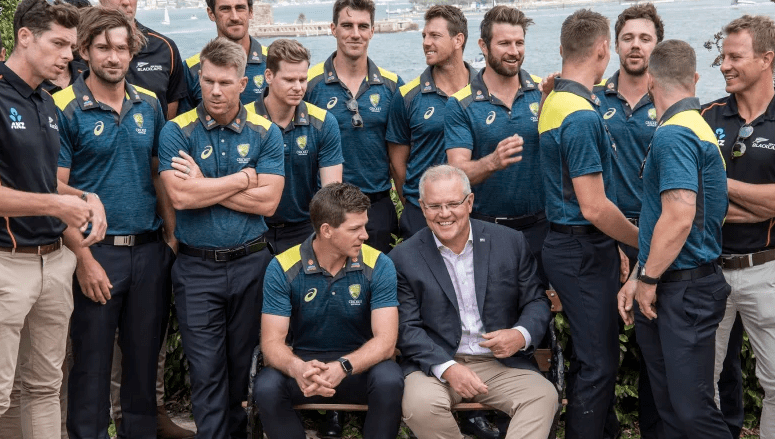

Though much has been written on the rights of elite athletes to give social commentary, comparatively little has been on to the ways in which sport is exploited by political elites. Sport has a unique role in our new environment of “optics” politics: where all that matters is the photo op and mere pretence of integrity in our institutions. By virtue of its unique position as a sacrosanct public space, it has incredible power to be leveraged in a politic obsessed with imagery – and politicians know this. Morrison’s great hope in Tim Paine’s men “giving us something to cheer for” is not merely that of distraction from his own leadership (or lack thereof), but a calculated investment in this nebulous idea of a national collective, a jingoistic mechanism by which voters forget the sins of his government. At first glance, one might think he is attempting to adopt John Howard’s image as a daggy sporting tragic, a brand that won four elections. Thus far, it’s been an effective ploy for Morrison, who ends his press conferences with a confected “Go Sharks!” despite being a union man from Bronte. The investment in optics, above all else, is an art he seems to have perfected: the majority of his Prime Ministership has been spent running for office, indiscriminately splashing cash at sports clubs (as long as they were in marginal electorates). He won that election convincingly – it would be easy to take away that whipping out a garish scarf and having a decent drop-punt is a surefire electoral winner. On further analysis however, Howard built his brand not on a love for sport (or indeed any ability), but on nationalistic symbolism. It was Howard who placed the Test captaincy on a pedestal above even his own job in terms of importance, and would milk the personalities that held the office for soundbites that embodied what it meant to be Australian: Mark Taylor was humble and honest, Steve Waugh a gritty warrior. It’s no coincidence that his famed power-walks were performed in the most garish of green and gold tracksuits.

Cricket may be the quintessential Tory game, but it is not unique in its capacity to be leveraged for political gain, nor is that gain necessarily solely the preserve of the right. Sport’s role as a political mechanism is contested – there is a long history of sport being used for progressive protest, and particularly by Australians. The 1968 Munich Olympics are remembered for the silent Black Power salute of victorious American sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos on the podium of the 200m sprint. They were joined by a white Australian, Peter Norman, who stood solemnly in solidarity with an Olympic Project for Human Rights badge on his left breast. For his principle, he never ran at an Olympics again. Even in death, Parliament refused to acknowledge the racism involved in his blacklisting. 52 years after they blacklisted Norman, the Australian Olympic Commission has supported an International Olympic Committee ban on political protest at the Tokyo Games later this year. The fact they also supported Mack Horton’s refusal to share the podium with alleged doper Sun Yang at last year’s Swimming World Championships betrays that it is political protest, not protest generally, they are wary of.

It is not misplaced – conservative sporting establishments have every reason to fear the rise of sport as a political arena after a summer where using it for distraction has been rejected with the white-hot anger of a public sick of being taken for fools. 2020 looms as a year of political action in the sporting arena – no doubt the Prime Minister will hope for Ellyse Perry to lead the Southern Stars to victory in March so he can crow about sports grants. But he would do well to remember our athletes don’t tend to like smoke inhalation, and the rumblings we have heard this summer are set to become deafening. In this environment, we would all do well to be conscious to be critical of the political messaging involved in our sporting entertainment this year.

This article was originally published in the Week 1, Semester 1 edition of Honi Soit.