When three baboons escaped from Royal Prince Alfred Hospital (RPA) two weeks ago, in their reporting on the event, The Guardian repeatedly used the same stock image of an olive baboon, found throughout equatorial Africa, despite the escaped male baboon’s obvious mane of grey-white fur and red face announcing him as a hamadryas baboon from the Horn of Africa and Arabian Peninsula. While a mistake as obvious as this should reveal poor journalistic standards, it is likely to go unnoticed by readers as the majority of us know very little about any other animal species: their forms of embodiment, social and kinship structures, dietary habits, lifespans, preferred habitats, technologies, means of communication and self-expression.

This is the result of the entrenchment of urbanisation and industrialisation, which has transformed space in the European imperial core and its colonial outposts including the Australian settler-colony, razing other animal habitats and constructing our own out of concrete, timber and steel. In the process, other animals have been banished from their own homes to make way for ours. Those that remain such as rats, pigeons, ibises and cockroaches, are seen as ‘pests’ in their defiance of human attempts to banish all other animals (besides our pets, eugenically curated to suit our aesthetic preferences) from non-‘wild’ space. While in many other parts of the world, including more remote parts of the Australian continent, people and other animals still coexist and share their environments, most of us in the Global North have never engaged in an organic relationship with a non-domesticated animal. And through colonisation, First Nations peoples’ totemic cosmologies have been removed from their original context, involving relationships with and knowledge of animals and the land.

It is partially because we have learnt to never see non-domesticated, non-bird species in our midst that the sighting of three hamadryas baboons was so shocking to passersby. Of course, a great part of the shock came from the knowledge that baboons are not native to Australia and do not exist in the Australian bush or urban landscapes. But that does not mean that they, and other primate species, are not prevalent within Australian borders. Most readers have likely seen various species of baboons, gibbons, orang-utans, and gorillas imprisoned within some of the 61 zoos currently operating in Australia. But behind locked doors, razor-wire fences and security clearances are a number of medical testing facilities which often use primates like baboons because of their relative ‘closeness’ to humans in terms of DNA.

The Aussie Farms ‘Farm Transparency Map’ reveals 10 medical testing facilities in Australia, including the Australian Animal Health Laboratory which does research into emerging infectious disease threats to livestock and aquaculture fish in order to bolster the profits of these industries; the DPI Elizabeth Macarthur Agricultural Institute, which contains and researches upon animals for the purposes of Australian biosecurity; the National non-human primate breeding and research facility at Monash University; and ozGene, which breeds ‘customised genetically modified mice’. Evidently, the common use of animals in research does not take place purely out of the goodwill of scientists trying to make the world a ‘better place’ by alleviating human illness—it is directly related to the need to maintain Australia’s profitable livestock sector despite its negative environmental impacts, its ongoing role in colonial dispossession, and its brutalisation of other animals.

The baboons came from the National Baboon Colony at Wallacia which is part of the Sydney Local Health District, a division of the NSW Government Department of Health. Amongst other organisations it has historically received funding from the National Health and Medical Research Centre (NHMRC). According to data available on the NHMRC website, during its 2017 Grant Application Round, the NHMRC allocated University of Sydney researchers at least six grants using so-called ‘animal models’, totalling $5 million.

While no 2018 University of Sydney (USyd) grants from the NHMRC mentioned animals, at least 35 grants from universities across Australia did, including Monash, the University of Queensland (UQ), UNSW, and Adelaide University. Most grant descriptions did not specify which ‘animal models’ they intended to use—those that did mentioned ‘mouse models’ and one grant awarded to Professor Mark Walker from UQ mentioned the use of non-human primates in research into a Group A streptococcus vaccine. The grant description advises that the use of animal testing “will underpin commercial decisions by our industry partner (GSK) leading to human trials and the development of a safe group A streptococcal vaccine for human use.” GSK—Glaxo Smith Kline—is a British pharmaceutical company which was fined US$3 billion in 2012 for bribing doctors to prescribe their antidepressant medications to children and failing to report safety problems with diabetes drug Avandia. USyd also collaborates with GSK, through an ‘Industry-Based Learning Program’ offered to undergraduate students in their final year, reflecting the rise of public-private partnerships in the education sector.

While mice are traditional in vivo test subjects, primates are often used as alternatives where transgenic mouse models fail, due to their closer physiology to humans. Due to the size similarity between human and pig organs, researchers at USyd including Alexandra Sharland have been doing research into xenotransplantation between pigs and baboons, with the ultimate goal of using animal organs for transplantation into humans. Sharland has been part of 6 research teams receiving grants from the NHMRC spanning 2000-2015 for research into xenotransplantation. It is highly likely that this research has involved baboons from Wallacia.

In this way, other animals are constantly being evaluated for their exploitation and commodification based on their proximity to humanness—in some cases primate closeness to humanness leads to concern for their ‘conservation’, in other cases it makes them research subjects to have their reproductive functions controlled, bodies mutilated and existences confined to labs and cells. Historically, racialised, colonised and criminalised populations have also been used as test subjects due to their perceived loss of proximity to humanness, such as human vivisection experiments carried out by Germany and Japan’s fascist regimes during World War Two, or the infamous Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment carried out on African-American men. In Australia during the 1920s and 1930s, First Nations people were subjected to medical experiments by the University of Adelaide justified by a regime of scientific racism.

While many student-led campaigns emphasise the importance of showing solidarity with university staff and defending the right to university education, I think we also need to recognise the way that the academy has been the originator of many discourses and practices that intellectually bolster colonial regimes, develop techniques of power for capital and the state, and deepen the hierarchies of class, race, sex, ability and species which make up our world through knowledge production and technological development.

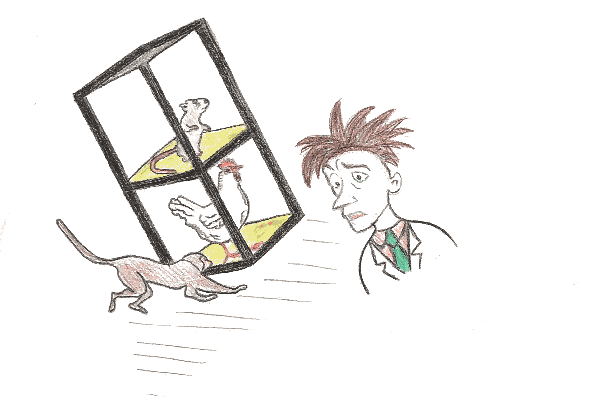

There are other ways that we can know other animals than through the disciplines of natural science which seek to objectify and instrumentalise their bodies, the voyeuristic spaces of zoos and aquariums, or shallow pop culture representations. When I saw the footage of the baboons’ escape, I saw three agents affirming themselves against the speciesist power of the medical institution that they were escaping from. I read their activity as a form of protest, a way of thwarting the people who depended on their bodies for research funding and clout within their discipline. Although they were eventually captured, on some level their protest was successful: it generated discussion in Australian news media about animal testing, sparked a protest outside RPA last week, and created new knowledge of vivisection.

However perhaps what was missing from the news and from the animal rights protests was a knowledge of the baboons as agential subjects with whom we can stand in solidarity, not simply pit or feel the need to ‘save’. I heard fellow vegans describe how scared the baboons must have felt on the streets of Sydney, when really I think they would have been relieved and overjoyed to be out of the confines of the hospital being able to move about on their own terms. Ironically, it was this welfarist idea that was used to legitimate Taronga Zoo handlers recapturing them.

Ultimately, what propels forward my politics as an animal liberationist is the desire to know other animals as they know themselves: as subjects of their own experience. I would encourage anyone who currently views other animals as alien to their existence to cultivate that curiosity.