“It was 3am in the morning, Easter Sunday. All was silent except for the tingling sensation of the music from the evening’s concert in my mind with the streaming moonlight casting its shadows. I was feeling exhilarated, inspired and moved. I was in the sleepy town of Bendigo, Melbourne in 1986 and I recall finding my home in his music. This was my first meeting with Pandit Ashok Roy.”

This quote comes from the creator of a WordPress dedicated to my grandfather. I would have preferred to recount his delicate, visceral performances, to have sat in crowds and felt liberated by the sense of community that typifies any potent music but his memories, for me, are shaped, transformed and deceived through the recounts of my family and his passionate supporters. You could read the above recount after any show, whether that be techno-heads drifting in and out of their bodies, watching lights being mutated into abstract shapes through trees, on the floor, in the faces of others; whether that be giddy teenagers exiting arena shows adorned in glitter or punks dwelling in the after-glow of bruised bodies and frail necks from a metal show. But reading the words, “this was my first meeting with Pandit Ashok Roy,” makes my stomach heave – a lumpy, murky, scrambled feeling of weight and indirection, like a helpless object entangled in seaweed.

We perceive most artistic mediums through images. Stories especially are grounded in their ability to help us bring them to life. Images are coherent and objective, words transform the way they are represented. But words can be misleading. Your own garden is different to the Garden of Eden. A few other mediums like music aren’t imagist and instead rely on symbolism. Music is a language in and of itself but one that is somewhat esoteric and, for the most part, very personal. Thus, to attempt to listen and moreover to appreciate this foreign language, we rely on our ability to be open and welcoming enough to digest its various intonations, deceptions and eccentricities. If we can do so, music has the ability to shed some sort of revelatory light on our own ability to accept difference, to see the world in a way that deforms our preconceptions, to realise things that may have gone unnoticed before.

For many people, my grandfather’s music was the catalyst for this defamiliarisation of their worlds. I never got to experience that; I experienced baba in a more fractured, more impersonal sort of way.

There were many times that my brother and I went to his house. We went there for no other reason than to eat my grandmother’s chicken curry. The place was two stories with tinted windows and a strong, mahogany door on the outside. Inside, the carpets were tattered. Walls cracked with water damage. The house reeked of spices and ash. My grandmother’s black cat, ‘Gopi,’ came occasionally to say hi but I’m sure she could sense my trepidation at her discomforting yellow eyes and the slinky way in which she lurked in cobwebbed, dark corners around the house.

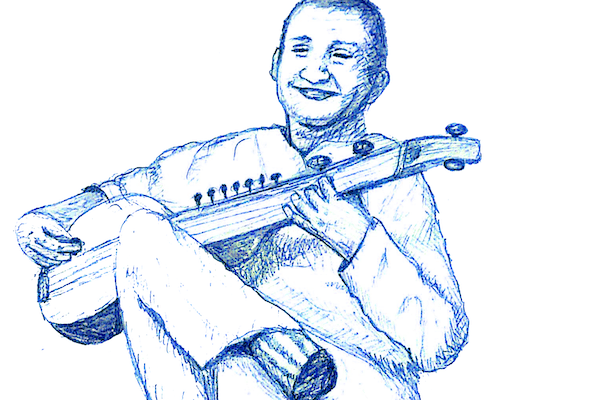

There is one photo that I have of me as a toddler, seated beside my grandfather as he plays the sarod. I wonder whether this is the only one. I’m sure he greeted us when we arrived for those lunches but as soon as my grandmother’s amicable personality took over, he would retreat quietly upstairs and play his sarod, a 17-stringed instrument which is one of the most popular Indian classical instruments along with the sitar and tabla.

Little me and baba.

I recall a story my father once told me about the intensity of baba’s practising habits. He recounted it while looking outward, seemingly searching for baba’s presence amidst the slow-moving clouds, or the shallow blues of the sky. Apparently, and this happened more than once, my grandfather would light a cigarette just before the beginning of a raga and as he slowly became controlled by the whims of himself and the song, he would forget about the cigarette. It would burn to a stud and hang languidly from his mouth as the raga, often more than fifteen minutes, reverberated inside the cramped walls of his practising room.

I try to picture his hunched over posture, eyes closed and flickering, in some sort of in-between space, ephemeral like the fleeting moment before we fall asleep. I try to picture the delicate way that his fingers pluck the thick chords, the pinky nail, forever long, that mutated into a pick. Sometimes, I try to feel the stiffness of his back, the ache that shies away after it is ignored for hours on end, the totalising vibrations of the intricate and whimsical sounds echoing from his equally whimsical fingers. I try to imagine what it might have been like to drift away from my body the way he might have done. To drift and be thrown around and suspended amidst the concoction of sounds spinning, crashing and exploding around the room like the frenzy of a beehive kicked by an irreverent child.

I try to imagine these things but every time I do, hand wash, white lights, and sterilised smells try to unravel them. Baba’s penchant for cigarettes and dedication to his craft led to a leg amputation, numerous bypass surgeries, failing kidneys and the consistent accompaniment of a blood glucose monitor for his diabetes. By the end, in 2007, I think I was at home fast asleep. Years later, my parents recall that he died as soon as they left the hospital in the early hours of the morning, as if he waited for them to leave so that he could finally succumb. It’s easy to think that baba was a shell of himself when he died – deteriorated, weak, skeletal, even partially human because of his amputation – but the way in which he seemed to exercise self-control even over his death, suggests a sense of exaltation that typified the sentiment people attached to his music.

As easy as it is to create a shopping list of the physical detriments to his body, it is also easy to do one of his musical achievements. In 1987, the Sydney Morning Herald said, “Ashok Roy is one of the great exponents of the Indian Sarod.” He won the All India Radio (AIR) Instrumentalist of the Year Competition in 1960, toured Europe and the UK as part of the UNESCO Collection of Musical Sources, held a position with the Indian Council for Cultural Relations (ICCR), was an artist-in-residence at Monash University, taught at the Victorian College of the Arts (VCA), became the artistic director of the Australian Institute of Eastern Music (AIEM) and recorded two albums of traditional music with the ABC. Arguably, the culmination of his glittered career came when he was nominated for a Best World Music Album award at the 1997 ARIA Awards.

Ashok with his guru, Ali Akbar Khan. Khan, nominated for five Grammys, was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship and alongside Ravi Shankar was a key figure in popularising Indian classical music in the West.

It was an unintended consequence of my thought-process that the halfway point of this essay is defined by baba’s significant physical and musical moments because, for all the people that enjoyed a deeper connection with his music, these are the seminal moments that define the way in which I reason, understand and engage with his life. In the same way as I perceive him through sickness and his formal achievements, I could have easily circumvented any misrepresentations in defining my relationship with him by filling the essay, like the opening, with a long-winded collection of other people’s remembrances of him, his music, his personality and his teachings. To be honest, Baba/Ashok’s memory belongs more to the world than it does to me, or maybe even my family. Ashok the man is trumped by Ashok the musician, and his presence throughout the world lives in minuscule moments of inspiration and nostalgia. Some dwell in the fact that his music was enchanting and a momentary transportation into a fantastical, heavenly world. Some remember him for his foresight, his ability to facilitate multiculturalism through music before it was a political fetish. Some simply appreciate his passion, his tactful teaching ability. Some bask in his artistry and indifference to popularity. Others see, hear and feel him just as one remembers a lover or a place: through random, abstract and often invisible smells or sounds, which bring a sudden and unusual sense of comfort that surrounds you like a coffin before vanishing as lightly and as insignificantly as a bird lifts of a branch.

Ashok performing in Fiji with Bhagwan Pandey, as a cultural ambassador for India.

Sometimes I wish I could tell my friends, or other interested people about a personal story I have with him, or a moment when I saw his performances in the flesh rather than recounting the aforementioned list of his achievements. I can’t, and I’ve decided that it is ok. In fact, it is sometimes nice to have your memories, your emotions dictated by others. In a way, they feel more trustworthy and real, not tinged, like my other memories are, by the deceptive way in which perspective changes with age and the haphazard, nebulous and illusory way in which we picture moments of our past. When people ask me what my earliest memory is, I say it was when I rode for the first time without training wheels. Aside from the cracked concrete outside my house, the maybe blue colour of the wheels and the manic churning of the pedals I remember nothing else. I sometimes think I hear the support of my mother, or the scrape of the surface, maybe even what the sky looked like but it is foolish to think that these are genuine.

In the same way, I would hate to have the memory of my grandfather defined by gangrene, townhouses, long finger nails and curry. I need the memories of others to shape my memory of him and to allow the pervasive nature of his influence to seep into some of the actions of my own life. It’s okay to be selfish in our remembrance. It’s okay to manipulate and to plagiarise thoughts that aren’t ours and to shape them in a way that provides us comfort. There are so many things that cause discomfort, so is there any harm in occasionally deceiving ourselves to believe something that we weren’t ever in a position to believe?

For me, the idea that my grandfather favoured artistry over commercial success is inspiring. When asked about him in an article for the ABC, my father said, “it doesn’t matter whether you are playing with an unknown musician in a café in Enmore, what matters is that when you play together you should feel something in your heart. The feeling and love is what matters the most.” If I read that quote in any other interview or magazine, I would have found it reductive and cliched. It’s different when, for a very rare moment in life, I have an insight into the logic behind a cliché. Someone told me that the work of a writer, or any artist for that matter, is to express what can’t be expressed in words. I am sure my grandfather did that but it is the task of his audience to accept and to translate what they hear. At times when the intention of the creator is abstract, the onus falls on a responder to carry the work forward, to facilitate its transferral and to find relatability in its incomprehensible construction. Very few people will know the intricacies of strings, the way they fuse together, the purpose of the chikari, the technicality of slides and the only way to mitigate this lack of understanding is to lean on words like ‘feeling’ and ‘love’ that don’t really mean anything in isolation but require something unexpected and so defamiliarising to what we know that we suddenly realise their true meaning.

When I was contemplating writing this, I received some hesitancy from my parents. They asked me why any Australian student would want to know about an Indian classical musician who spent his life dedicated to an instrument that they probably never heard of. Most people probably don’t and to be honest, I don’t think I would have read something similar. I wrote this for myself and I only can write this for myself because I have nothing else tethering me to our relationship. It is a collective endeavour to commemorate but an individual one to relate. My story is singular, my relationship probably fractured, but it is via the nature of his music that this story unites with so many others. A mosaic can only find clarity when all the jagged bits are put together. I think my grandfather would have been proud to know of all these jagged geographic and mental interconnections formed by his life’s passion and to know that his memory lives on through words that try to understand a language that he crafted on his own.