Emilie Bickerton, author of a history of the magazine, declared Cahiers du Cinéma a “dead sun” in 2006. Cahiers has therefore achieved something really remarkable in the past week – a death from beyond the grave. On the 27th of February, its entire staff resigned in protest against the magazine’s sale to a group of shareholders led by banker Grégoire Chertok; these shareholders included eight film producers.

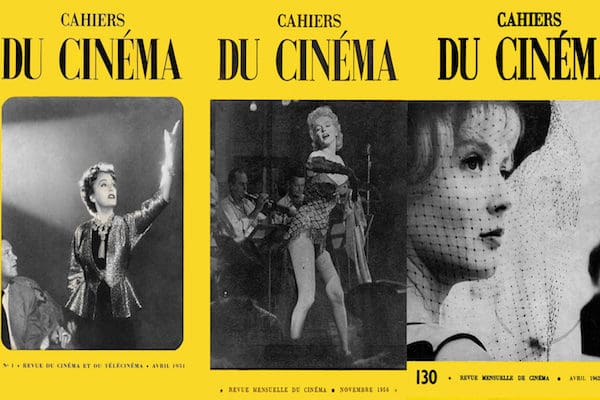

The magazine was begun in the 1950s, under Andre Bazin, and with a roster of no-name critics including Jean Luc-Godard, Eric Rohmer, François Truffaut, Jacques Rivette, and Claude Chabrol – all of whom went on to be core members of the 1960s French New Wave. Despite the publication’s decline in reputation in recent years the more irreversible nature of this self-destruction seems tragic for film culture. And yet, also stirring, an act containing something of the quality of those energetic polemics which made Cahiers the most important journal in film history.

It wouldn’t, however, be too difficult to find the actions of the editorial board excessive. At least two items of protest may strike one as business as usual. The new managerial team wanted to make the magazine “a little more chic” and “convival… critical without being insulting”, as well as looking into new partnerships with organisations in the film industry, in particular the Cannes Film Festival. It should be noted that the two pre-eminent English language film magazines seem already to have succumbed to such directives – “Sight & Sound” and “Film Comment” are published by the British Film Institute and the Film Society at Lincoln Centre respectively. The more obvious problems are the conflicts of interest created by having film producers on the board, as well as fears that the boards ties to the Macron government would restrict Cahiers critical attitude towards the administration. Overall, it seems worth conceding that the situation itself is not exceptional – it is firmly within the bounds of what we’d expect to occur in modern journalism – but the act of quitting is quite remarkable, especially when considered as continuous with the history of the journal.

A fierce independence is at the heart of Cahiers du Cinéma. The initial group of critics were held together by a set of shared tastes and beliefs that were considered, at the time, quite radical and which had to be fought for to be accepted. Most important were the “politique des auteurs” and the concept of “mise en scène”. To establish film as a personal art, they uncovered the signature of certain “auteurs” throughout their oeuvre. To establish the merits of cinema as an art form, they were attentive to what was cinema’s own – the organisation of visual elements into mise en scène. The two lines of argument enriched each other. In contrast with that impoverished, dominant criticism concerned only with ideas and themes, auteurist criticism took the film, or in fact the auteur, as a whole and elucidated an attitude towards the world. Their guiding lights were Renoir and Rossellini, but their taste was particularly influential in the re-evaluation of Hollywood filmmakers like Alfred Hitchcock, Howard Hawks and John Ford as serious artists.

By the 1960s, Cahiers had essentially won the war. The major critics of the 1950s period had become world-renowned filmmakers. Their theories and tastes were spreading. The magazine was seen to be in decline – Godard claimed that it was “due chiefly to the fact that there is no longer any position to defend.” And yet behind Godard’s back, the 1960s Cahiers writers were forming a position. They found new life in refining, revising, and overturning the ideas of the 1950s – in particular, by politicising them, with an increasing urgency up to and in the wake of May 1968. Cahiers was thus heavily influential in the move towards structuralism in film studies. This was the magazine’s second Golden Era, but it wasn’t to last. By the mid-1970s, there was a feeling that Cahiers had to get commercial again, and this is seen as the beginning of their decline proper.

The 1960s period is instructive, because it shows us that independence is not merely to do with concrete threats, such as those facing the journal today. There are impediments to independence, but independence is not achieved simply by their removal. It is an act in itself. It is the taking up of a position.

What masks the absence of independence in film writing is that phenomena Jonathan Rosenbaum calls a “cultural confusion of criticism with advertising”. As cinema becomes a more marginal form, its institutions necessarily integrate. Distribution and criticism become entangled – economically, but also philosophically, both seen to be engaged in a noble battle to preserve cinema. There is scarcely any effort though to define what that cinema being preserved is. In other words, cinema’s excellence is assumed, and explained in received terms. It is not necessarily that critical values are all wrong, but rather that films are received in terms of a continuous proof of the medium’s vitality, rather than a gesture towards its potentiality. This prepares the way for the ecstatic reception of academic films like Bong Joon-Ho’s Parasite and Celine Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire, but leaves Angela Schanelec’s unclassifiable I Was at Home, But… unattended.

In Jean-Luc Godard’s 1960 film Breathless, a very memorable Jean-Pierre Melville claims that he would like to “become immortal and then die.” All brands, including Cahiers, are of course immortal. Now though, Cahiers have done the decisive, fulfilled Melville’s maxim, and died. Other publications shouldn’t follow suit, but certainly the relative similarity in their different positions should be considered, and our appreciation for and recognition of independence strengthened.