When someone asks me to define myself, I reply, confused, “I would say, someone who has grown up waking up to the morning azan?” The morning call from the minaret was usually infused with the rosary breaths of my mother, the lunchbox clamour of Farah aapa from the neighborhood, groans of morning obligations, and other womanly sounds. You would expect the colony to ring with the domestic callings of women, but hardly expect to hear words like Inquilab and Azadi.

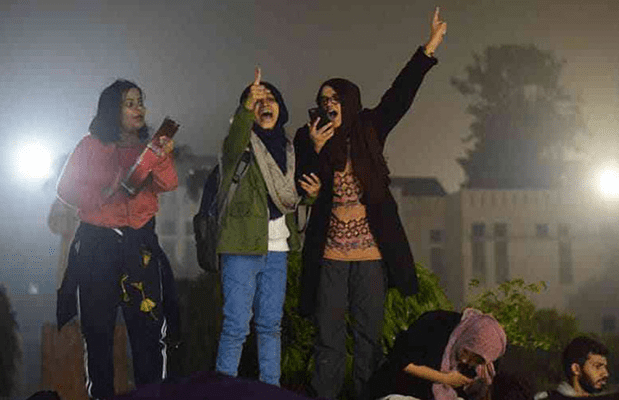

India has witnessed an already tumultuous political situation flare up in the past three months following the BJP government’s decision to pass the Citizenship Amendment Act, a discriminatory act which provides citizenship safety to people of religions other than Islam. This act has been received with dissent from all over India, and the world. Women, and especially Muslim women have been at the forefront of the dissent that is circulating throughout the country. My goal here is not to say that only female protestors should be glorified, but to reflect upon how seeing women I have grown up with out on the streets made me feel something in my gut. There was just something about seeing them with their fingers up in the air that made me wonder what offence they will stir amongst the rigid right-wing.

Shaheen Bagh has gained popularity for being the longest running peaceful protest in India. This idea of 24-hour sit-in protests was proliferated to places like Lucknow, Mumbai, Bengaluru and Varanasi. I could not physically attend the Shaheen Bagh protests, but attended Mumbai Bagh, a similar 24-hour protest that happened in Mumbai. However, I need not be physically present to tell you about the reactions that people (read – privileged upper caste Hindu men and women) have thrown at me for talking about it.

There is this sense of discomfort among people when they see overtly Muslim women being the face of something dynamic. Mind you, the issue is not with women, or Muslim women who are latent about that identity. The offence arises when the right wing see women who carry any trace of their Muslim identity – a hijab, the Qu’ran in their hands, some Islamic chant, or simply the statement “as a Muslim woman…” – out and proud. It is like we are matchsticks and can only escape their matchboxes when they want to light a cigarette. The discomfort that Muslim women bring to the right wing is clear not only in high-profile politics , but also in day-to-day interactions.

The women – led protests are happening in Muslim neighborhoods and are led by Muslim women; a combination of topographical and gender anomaly in the Indian society. It is this game of image that comes here. If you are a Muslim woman in India, the assumption is that you are either an uneducated, submissive wife or a sensuous, promiscuous woman. The former comes from a place of geographical and societal history of oppression.

My family grew up in the chawls of Nagpada in Mumbai and women of my family do not have much formal education. I have seen the women of my house in hijab all my life, and I have always associated them with sewing machines, spoons, and pots. However, when I see the current protests in Mumbai happening in the same area, and the clinking of pots and pans on protest grounds, I shiver. I hear my grandmother, and think about how the women were up all night in solidarity during the 2002 Godhra riots, how their spines twitched at the radio updates, and how they prayed through the political tumult that night. The fragility of the right winger does not see this. There is this image which has settled in their minds, of us growing up by the sewage, being imbued with jihad. If we ignore politics, we are docile. If we talk politics, we are terrorists who will burn down your shops on the orders of the men in our lives. If we try to sensitize our fellow sisters, we are wayward thinking people dismissing our religion.

I have had all sorts of conversations with people, with some questioning how the “poor’’ Muslim women know about the political reality of the act. My discomfort with that term is another tale, but the lack of efforts from the opposition to understand the reality of the protests is appalling. Protests like these stimulate volunteer and educational circles, sensitising people about the issues and making them understand their stakeholdership in the revolution. These circles are a feminist conundrum of shared understanding and tranferring of information from women with more access to those with lesser access. When I tried to explain this to some acquaintances, they dismissed this by saying, “anpadh auratein dusre anpadho ko padhayengi?” (how can a group of uneducated women teach another group of uneducated women?) The assumption that we are uneducated comes from the sight of the hijab, the assumption that we cannot have a different life while living in such areas. My aunt, a chemistry professor, who lives in Nagpada and runs a volunteer group at Mumbai Bagh tells me how everyone assumes she is a nobody because she wears a hijab and communicates in Urdu. “Wo kehte hai ki maine mera inquilab mardo se seekha hain. Par mai toh bachpan se hi meri behno ke sath azadi ko pyar samajhti hu.” (They think that I have learnt resistance from the men in my life. But I have romanticized revolution with my sisters right from my childhood).

When I went to Mumbai Bagh to protest, I saw girls of the age 12 – 18 sing azaadi in chorus until 10 pm. They then resorted to simple learning circles after the time. All I saw was an unquenchable female anger that I wish I had when I was 12. They say we protest for their money, and I ask how, how do you get the audacity to make such claims? For a large circle in Indian society, Muslim women are still the money hungry tawaiffs and prostitutes. We are either our names, beauty, or poverty. I ask here, a simple question to all –

Tumhara inquilab, inquilab. Par hamara inquilab jihad kyu?

Your resistance counts as resistance, so why does our resistance count as terrorism?