As the last specks of glitter (biodegradable, of course) disappear from Oxford street, and the flurry of rainbow, feathered and leather outfits are pushed to the back of cupboards, it is clear that Mardi Gras 2020 is over.

The celebrations in Sydney were spectacular and the overall attitude of the city was joyful and inclusive. This may give the impression that LGBTIQ+ welfare is at an all-time high but it is important to remember there is still a long way to go.

According to the National LGBTI Health Alliance, transgender people over the age of 18 are still nearly 11 times more likely to attempt suicide in their lifetime than the general population. Transgender people are also far more likely to experience violence, homelessness, unemployment and barriers to healthcare access.

Poland’s recent adoption of LGBTIQ+ free zones and of course the Trump administration’s proposal to roll back the transgender protection legislation adopted by Obama proves that discrimination still exists on a global scale.

Last year The New York Times infamously reported that in a memo they obtained from Trump’s health department, it was proposed that “sex means a person’s status as male or female based on immutable biological traits identifiable by or before birth.” Shockingly, even the World Health Organisation (WHO) classified being transgender as a ‘mental health condition’ until May last year. This is simply false.

Scientific understanding of the basis of sex and gender is still growing, but one thing is absolutely clear: gender is non-binary and gender incongruence, the feeling that your assigned sex does not represent your gender identify, is real. We also know that people can be intersex, that is, they have natural variations of their sex characteristics. Thus not even genitalia fits into the binary categories of male or female.

The research in this area is complex, revolving mostly around genetic factors, hormones and neurobiology, and their interplay.

Let’s talk genetics.

Genes are segments of DNA which dictate body features including hair colour and height. There’s no single gene that encodes for sexual preference or for gender identity. However, large population studies have shown that being transgender can run in families, which means that genetic factors certainly come into play. Recent genome sequencing studies have expanded on this finding and have suggested that genes that make up certain hormone signalling pathways are likely to be involved in gender incongruence.

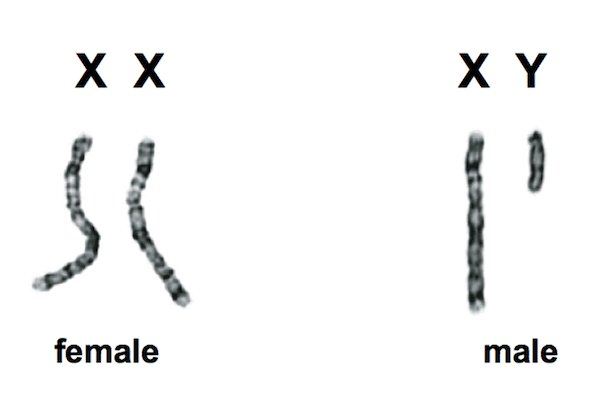

Genetics determine whether an embryo will develop to have XX or XY chromosomes. Embryos with XX chromosomes will generally develop ovaries while XY will lead to testes. We now know that XX and XY are not the only possibilities, as people can be born with natural variations of these chromosome combinations. And chromosomes aren’t the only important factor impacting biological sex determination, hormones play an important role too.

Oestrogen for girls, testosterone for boys?

We are taught as we grow up that females have high levels of oestrogen, while boys have a lot of testosterone. This is not entirely true: all people have oestrogen, progesterone and testosterone. During puberty these hormones are generally present at higher levels and do tend towards one end of the spectrum. During this time, hormones cause the development of secondary sex characteristics including external genital and other physical features. What we are often not taught is that adults generally have similar levels of these hormones, irrespective of sex or gender. Furthermore, a multitude of environmental, social and behavioural factors also influence hormone production. This can lead to variations in development throughout puberty, as well as hormone levels over a lifetime, supporting the theory that hormone levels and physical sex characteristics determine sex and gender.

A male or female brain?

While there is no such thing as a male or female brain, various studies have found that there are certain structural differences between the brains of cis males and cis females. These include differences in cerebral cortex thickness (the thin neuronal tissue that surrounds the brain) and composition of white and grey matter (tissue components of the central nervous system that consist of various neuronal cells). Both of these features have roles in neuronal signalling.

Another feature of the brain that is generally structurally different in cis men and women is the central subdivision of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BSTc). This part of the brain is involved in emotional and behavioural responses to stress. In a range of structural brain studies of trans women and trans men, it was consistently found that the BSTc of a trans woman more closely resembled the BSTc of a cis woman, and the BSTc of a trans man more closely resembled that of a cis man than a cis woman. So trans men and women have brains that are more similar to their identified gender rather than the gender they were assigned at birth.

Genes + hormones + brains

Research conducted in the 2000s showed that during brain development, exposure to particular hormones can cause ‘masculinization’ (or ‘defeminization’) of the brain that will cause the developed brain to have so-called typically ‘masculine’ brain characteristics. This is part of the sex determination pathway of the developing foetus just before or after birth. Furthermore, a recent study that involved sequencing the whole genome of trans men and trans women identified variations in 19 of those genes, which were associated with the hormonal signalling pathways involved in the ‘masculization’ process. This data suggests that variations in these genes could mean that someone who was assigned as male at birth due to physical sex characteristics may not have undergone the hormone signalling required for ‘masculinization’ and thus will develop a typically feminine brain, or visa versa.

It’s a spectrum.

There is plenty of scientific evidence that proves that gender incongruence is real. What the science also shows clearly is that sex and gender are in no way straightforward or binary and there are many complex factors involved. The terms ‘cis female’, ‘cis male’, ‘transgender male’ and ‘transgender female’ are not even adequate to describe all the members of the gender-expansive community. Intersex people can also be born with a wide range of natural variations in their sex characteristics, including chromosomes, hormone profile, genitals and more.

So what does this mean?

While an understanding of the relevant science may be one way to help support people facing issues related to gender incongruence, we cannot simply minimise the complexity of the condition into facts and figures. What is perhaps more important is an empathetic understanding of the social and political issues still faced by trans people as well as other members of the LGBTIQ community and the work necessary to break down barriers.

In a society that can truly support and celebrate natural diversity within the human race, the joyful and inclusive attitude adopted during Mardi Gras should not be limited to only one night a year.