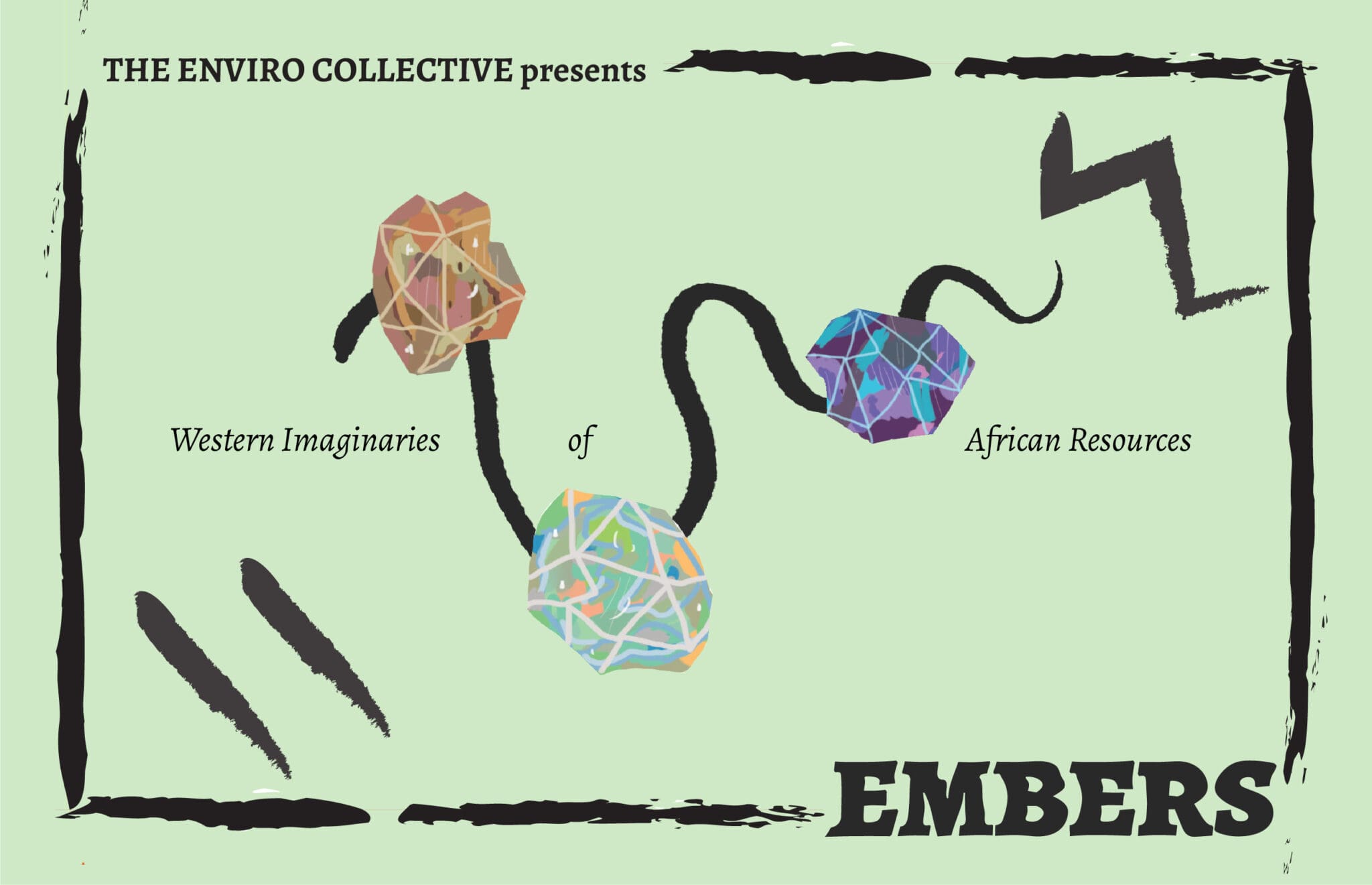

In the film Uncut Gems, Adam Sandler plays Howie, a frenetic jeweller on the run from debt collectors and his own impending gravitational collapse. It’s an arresting watch, full of claustrophobic tension. Running under the film’s pulse is an orientation towards the Global South and its resources, revealing its colonialist contours the more you tap away at it. Hovering just beneath the surface, dizzying.

Uncut Gems opens onto chaos at an opal mine in northeastern Ethiopia’s Wollo region. A man, badly injured, is carried out into a clamor of angry brown faces. The camera cuts inside the mine where two workers surreptitiously unearth a blue-green glimmer that drives the film: not a diamond, but surely bloody. Black labouring bodies become a disposable force, the weight of their physicality balanced neatly against the retrieval of capital for the West.

By the time the so-called black opal winds up in Howie’s hands to be sold to basketballer Kevin Garnett, it carries not just the legacy of violent extraction, but also an origin narrative of mythic quasi-religiosity. (As Jordan T. McDonald motions, the fact that Garnett, a black man, buys the opal complicates the white fascination–African spirituality dynamic, pointing to black diasporic desire and its complicity in colonialist flattenings of the global south; that in trying to grasp the ‘homeland’, warps it.)

Salvation, granted to the West by mythic ethnic powers-that-be, is a familiar narrative: popular culture is full of black or brown figures only valuable for the wisdom they bestow onto the (white) protagonist. Watching mainstream films and TV shows becomes a running joke: “Wow, [insert PoC character] is still alive?” Even more dominant is the collaroy of this colonial fascination: the west as benevolent caretaker of the global south. Generous, charitable, salvationary. Together these ideals create an ideal extractive apparatus; a project of violence that erases itself. This violence flows along with capital, in ripples of harm, glimmering as though oil on still water.

Kathryn Yusoff has brilliantly exposed the links between geology and systemic racism. Both carry a fundamental logic: value extracted from ‘inert’ matter, be it rock or black labour. In her book A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None, Yusoff writes, “White Geology makes legible a set of extractions, from particular subject positions, from black and brown bodies, and from the ecologies of place.”

Yusoff frames extraction as carrying a material history of colonialism: an ‘afterlife’ of harm. This spans “[I]ndigenous dispossession of land and sovereignty … through to the ongoing petropolitics of settler colonialism; of slavery … to the current incarnations of antiblackness in mining black gold; and of the racialized impacts of climate change.” These afterlives are at work in the capitalist flows of resources exported out of Africa and into the west; not only imprinted with past violences, but creating new traumas in their wake.

These extractive flows of oil, gold, diamonds, coal and platinum pried from African soil and rock are controlled almost entirely by private overseas corporations. African nations rarely use the products or see the profits of this extraction: a combination of tax evasion by the western corporations, lack of export taxes, and low rates of African governmental shareholding. A 2016 report by the UK organisation War on Want termed these extractive practices ‘the new colonialism;’ invoking in the frantic rush to plunder, a second imperialist ‘Scramble for Africa.’ Far from being new, the western profiting off exploitative extraction has always been an active element in settler-colonial state agendas.

A landscape of extractive capitalism complicates our climate justice organising. The framework of environmental racism draws attention to the unequal spread of climate change across the world; harm arrives first in brown countries, first on brown skin. So too is the spread of environmental redress unequal. In calls for renewable energy, who and what will continue to bear the cost? The pitfalls of ‘green-washing’ policies that leave capitalism unchecked have been laid bare by activists such as Naomi Klein. In Africa and the global south, green capitalism remains a tool for injustice: “exploitative and destructive” in nature.

Extractive colonialism and the western imaginaries that undergird it will only be undone when we dismantle the systems that do not serve us and build new worlds in their place. Recently, Arundhati Roy conducted a teach-in, thinking through her essay The Pandemic Is A Portal. She reflected on the nature of this current pandemic as a harbinger of new, more unjust worlds: “national authoritarianism is colluding with international disaster capital and data gatherers and they are preparing another world for us.” Can we refuse these?

I find myself turning to the world-building strategies offered by Afrofuturism; in radical PoC autonomy (in ‘F.U.B.U.’ Solange sings, “All my niggas in the whole wide world / Made this song to make it all y’all’s turn / For us, this shit is for us”); and pan-African resource re-distribution and solidarity (Black Panther for one; Born in Flames if you’re feeling spicy). Alternative imaginaries are powerful; they are speculative tools for environmental justice. Arundhati Roy looked deep into my web-cam and said gently yet firmly: “[this new world] isn’t going to be given to us like a cut fruit. We’re going to have to fight for it.” That’s dizzying in all the right ways; spinning me around to re-orient me towards justice.