In a news report by The Guardian, a protester monologues into the camera. Behind him are the graffiti-laden walls of Seattle’s police-free zone. He condemns the media’s depiction of the Capital Hill Autonomous Zone (CHAZ) as a space of dysfunction and violence and distances the project from agitators and “anarchists who want to fuck shit up.”

This opposition to anarchism is jarring. CHAZ was a near clear-cut example of a “temporary autonomous zone”, as proposed by anarchist writer Hakim Bey in his 1991 manifesto T.A.Z: The Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism. Clearly, anarchism is still a dirty word.

Yet, while not always labelled as such, anarchism is undeniably in vogue. In recent months, anarchism has surreptitiously crept into our everyday lives: from the establishment of CHAZ, to calls to abolish police and prisons, to the proliferation of mutual aid initiatives as coronavirus blanketed the globe.

Considered a brand of socialism by theorists such as Peter Kropotkin and Noam Chomsky, anarchy promotes the reappropriation of the means of production and the redistribution of wealth. But anarchists — staunchly opposed to all forms of power and hierarchy – steer well clear of party politics and bureaucratic, centralised modes of decision-making, thereby distinguishing themselves from democratic socialists or Soviet-inspired Trots.

Residing within the shadows of capitalist societies, anarchism remains misunderstood and frequently misrepresented. In the words of Hakim Bey, the media’s “vampiric thirst… to satisfy its junk-sickness for spectacle and death” has made anarchism a “blood-sacrifice” – a synonym for lawless dystopias.

Nor has anarchism found a home in academia. Distrustful of a technocratic elite replicating the behaviour of ruling classes, anarchism has developed an antagonistic relationship with academic institutions. Anarchism is sometimes mentioned in passing by lecturers, but more as a curiosity – a utopian fantasy unworthy of critical attention. More often than not it is ignored altogether.

Anarchism centres on praxis. More than an ideology, it is a lifestyle, represented not within the dust-laden pages of an esteemed academic journal but around a campfire at a bush doof, and around the table of a crumbling street-corner pub.

The proclivity among practicing anarchists for “criminal” behaviour including squatting, hacking, culture-jamming and reclaiming private property and public space means little self-documentation of activities. While anarchism may occupy physical space, it has rarely occupied the imaginative space of a nation state at work. With the links between anarchism and oral, cyber, DIY and “criminal” cultures, anarchist stories rarely enter state archives and public memory. This fuels the perception that anarchism represents nothing more than a utopian, escapist fantasy. Yet anarchism is about experimentation and delving into its recent past can present unique opportunities for learning.

* * *

The early 2000s is a salient period in Sydney squatting history, driven by a post-Cold War scepticism of state socialism, a growing anti-globalisation movement, post-Olympics gentrification and the success of the Broadway Squats (February 2000-July 2001). “Sometimes the community reaches a critical mass of people who are up for it”, says activist and artist Peter Strong. He suggests that squatting as a lifestyle and protest against the politics of urban displacement progresses “in waveform” and cites the occupation of the derelict, art-deco cinema christened the Midnight Star Social Centre (February 2002-December 2002) as “the end of an era”.

According to Mickie Quick, who joined the Broadway Squats, people were “looking at the social centres of Italy in the 90s – fantastic spaces quite a lot like what is happening in Seattle right now with a lot of social services for communities.”

From February 2000, a fluctuating number of squatters – usually around 30 – occupied a row of empty buildings owned by the South Sydney City Council intended for demolition. At the end of August, mere weeks before the Sydney Olympics were to begin, the squatters were discovered, kicking off a series of heated face-offs between the squatters, who barricaded themselves in, and police and council members.

The squatters exploited the international attention on Sydney and the fact that “it was the council evicting people to go to the media and go hell for leather”, Quick explains. These tactics worked in the short-term but it was only after “relentless” lobbying that the residents obtained a caretaker lease. “We went to every single council meeting to raise our case and battle for it,” claims Quick.

The Broadway Squats were unique at the time because the inhabitants were open about their activities, and the caretaker lease solidified this legacy. In Europe, it was easier and (somewhat) more socially-acceptable for people to legally squat an empty building – a wartime legacy of mobility. In Sydney, stricter criminal trespass laws meant that “the story was different. You got one knock on the door from the cops and you had to leave instantly.”

Quick describes the Broadway Squats as “truly interdisciplinary”. The squat action brought together students, architects, lawyers, plumbers, locksmiths, artists, musicians, anarcho-syndicalists and computer programmers in a festival-like atmosphere, and they received support from the Construction Mining Forestry and Energy Union (CFMEU). By dumpster diving at Broadway Shopping Centre, the squatters opened a café with a voluntary donation policy. It was “a celebration and rejection of the waste of consumerism and capitalism.”

Some residents formed the collective Squatspace, opening a gallery in an old locksmith shop. In contrast to the minimalism, white walls and polished wood of Sydney’s high-end galleries, Squatspace hosted a flurry of one-week-brief art shows and political film screenings. Free party culture reigned supreme, transforming the space into a cavernous construction site. According to Quick, artists were “wrecking right into the space” with site-specific installations. On any weekend, you might be greeted by the politically-infused hip hop of Elf Tranzporter, Izzy and Monkey Marc (later to form the iconic group Combat Wombat with DJ Wasabi). Or perhaps you would endure the aural assault of Toecutter inaugurating his latest batch of broken beats at a System Corrupt party.

Within days of obtaining their caretaker lease, however, the occupants were evicted.

Activists took this legal precedent with them when they occupied the Midnight Star Theatre several months later. From the outset, the occupation was focused on offering services to the local community rather than permanent housing. Certainly, activists took shifts guarding the building around the clock and Strong recollects that “there were a few little rooms here and there. But it seemed pretty temporary. Just people crashing there… crisis accommodation.”

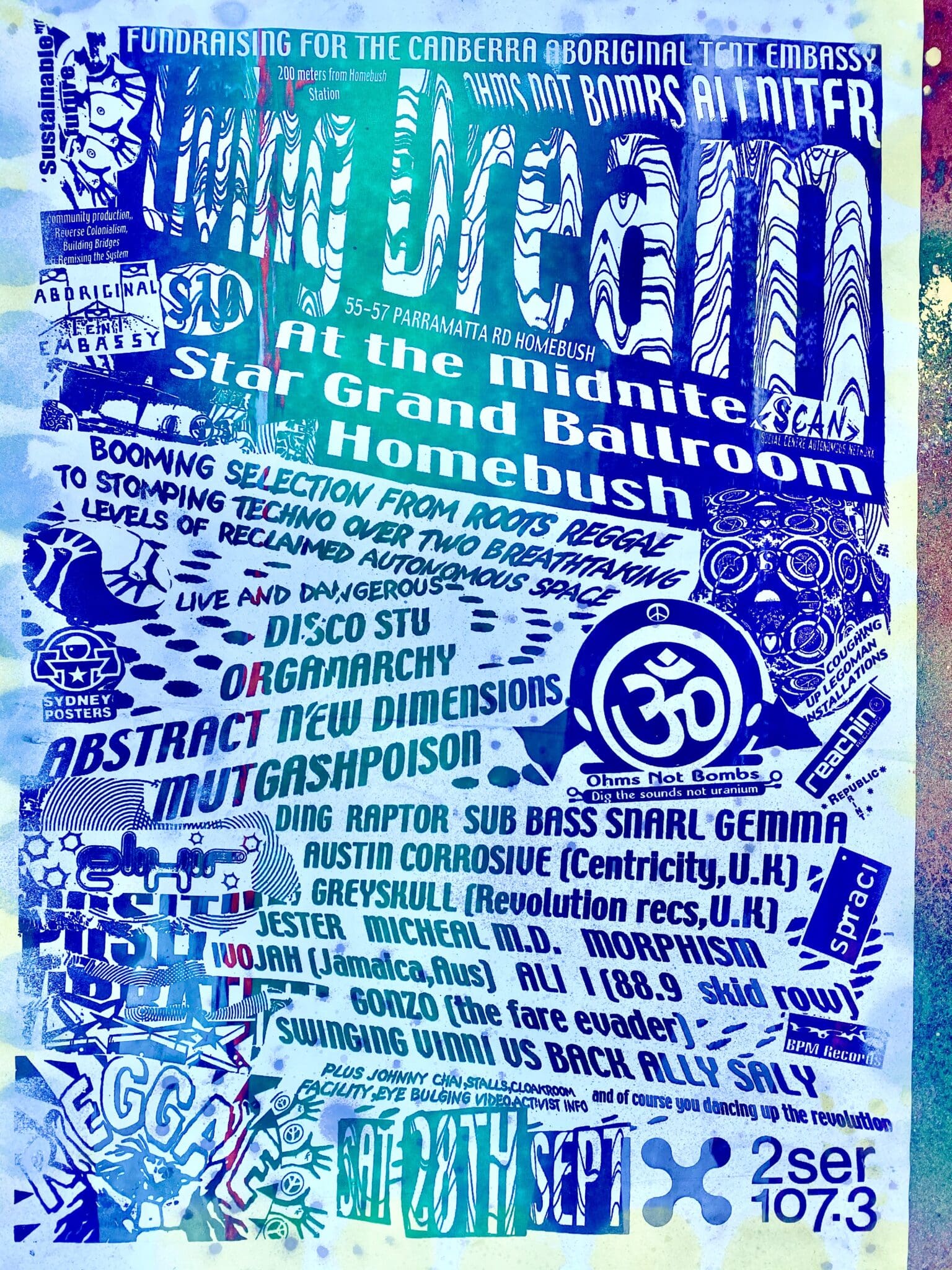

The Midnight Star was a “social centre”, a non-exclusive place of community, not a “squat”. It became a central node linking an underground network of anarchists, graffers, Indigenous agitators, party people, urban explorers and crusty punks – a network that branched off like fork lightning via anarchist bookshops (Jura Books and Black Rose), protestivals (Reclaim the Streets and Ohms Not Bombs) and community radio (2SER).

Strong looks back fondly on the Midnight Star. “Different groups would meet and have meetings and it was a unifying of those kind of left groups all coming together in the same space, rubbing shoulders and sharing ideas.”

The social centre hosted the after-party for the Sydney Anarchist and Autonomous Conference, pirate film screenings, raves, punk, reggae and hip hop gigs and, like the Broadway Squats previously, Squatfest – the agitator’s response to the corporate spectacle that was Tropfest. Food Not Bombs used the theatre’s industrial-sized kitchen to produce vegetarian meals for activists and community drop-ins. The Sydney Housing Action Collective (SHAC), meanwhile, a group of law students from UTS investigating squatting-related solutions to housing, curated a squatting expo in a side room, documenting Australia’s rich history of squatting.

However, Quick says the story of the Broadway Squats and Midnight Star Social Centre is “dispiriting”. While “the ideas were brilliant”, the Midnight Star was “a small flash in the pan”. “It fell over after really not a very long time and it has remained empty… That’s 17 or 18 years of what could have actually been a really successful social centre.”

Strong echoes a common belief when he asserts that the police clamped down on squatting because they feared that Sydney’s dilapidated buildings were fermenting political dissent. In December 2002, just two weeks after a WTO meeting in Sydney, riot police evicted the occupants of the Midnight Star. The subsequent Balloon Factory Social Centre in 2003 lasted only three weeks.

Anarchism has received criticism from socialists who viewed the post-leftist and individualist streaks that emerged within anarchism in the 70s and 80s as an active obstruction to leftist organising and a disdainful turn away from class struggle. But the criticism was not only external. In 1995, in his introspective essay Social Anarchism or Lifestyle Anarchism: An Unbridgeable Chasm, green anarchist Murray Bookchin frankly reflected on anarchism’s rising individualism. “Ad hoc adventurism, personal bravura, an aversion to theory oddly akin to the antirational biases of postmodernism, celebrations of theoretical incoherence (pluralism), a basically apolitical and anti-organizational commitment to imagination, desire and ecstasy” were suffocating the movement. “The black flag… now becomes a fashionable sarong for the delectations of chic petty bourgeois.”

But perhaps not all is doom and gloom. While the Broadway and Homebush squats did not enable squatting to enter the mainstream or reshape criminal trespass laws in practical ways, they were not necessarily, as Bookchin wrote, “more orientated towards one’s own ‘self-realization’ than achieving basic social change”.

Politically-conscious partying and art production were methods for squatters to engage a wider audience and transform worldviews. Rather than disconnecting from the world and receding into a privileged bubble of apathy, the squats, for a few brief moments, brought together diverse communities.

The links were particularly strong between Indigenous protest and the underground party scene. “We had just gone on the Earth Dream in 2000”, says Strong, “where the inner city anarcho-dance party protest thing went bush and connected with Indigenous peoples’ struggles and anti-uranium mining.”

In 2002 Strong co-organised Living Dream – a fundraiser for Canberra’s Aboriginal Tent Embassy at the Midnight Star – with the anarcho-sound system crew Ohms Not Bombs. “Aunty Isabel Coe came along and she spoke. There was an opening fire ceremony outside… The Victoria Park Embassy in Broadway had been an Aboriginal Tent Embassy during the Olympics and she very much spearheaded that occupation.”

The Midnight Star Social Centre allowed for, perhaps even encouraged by its very nature, the continuation of what charismatic millionaire Tony Spanos had begun in the 90s – engagement with First Nations communities and disenfranchised youth – through his philanthropy and ownership of the Graffiti Hall of Fame, a meatworks-cum-rave-venue.

It’s not unfair to say a level of pessimism has pervaded anarchism. Quick remembers raging at old Glebe squatters who would come to the Broadway Squats for events, having forsaken squatting. But he cites burn-out culture as a key reason for his inability to contribute fully to the Midnight Star Social Centre. Others claim the Midnight Star participants prioritised social events too heavily.

In a world of ever-increasing surveillance, paranoia and non-cooperation too are becoming distinguishing features of anarchism. Hakim Bey believed that “a bit of natural paranoia comes in handy” and suggested autonomous groups avoid publicity at all costs. But if today’s events show anything, it’s that perhaps there are more anarchist sympathisers out there than anarchists themselves believe. Indeed, despite some bad press from the Daily Telegraph, the Broadway squatters were able to wield the media as a weapon in their fight against eviction. We must take note.