Your phone, vibrating, jumps up and down on your bedside table like an infatuated, placard-bearing fan at a celebrity meet-and-greet, demanding your attention. In the inky darkness of half-consciousness, you reach out, fumbling for the device or the lamp switch. Whichever you strike first. It’s the lamp. White rays invade your eye sockets. You look at your phone. 130 unread messages. You look at the clock. 2 AM. Something about recording interviews with some stu pol kids. You sigh and turn off your phone. You turn off the light, sinking back into the heated spa of sleep, knowing it will be another early start.

Welcome to the life of an Honi editor.

* * *

Any reader of Antonio Gramsci will conceptualise mass media as an instrument for cultural hegemony – the concept that power can be exercised and reinforced as much through cultural texts as physical force. Contrary to the traditional perception of the press as an integral cog in democracy, holding governments and multinational corporations accountable, unequivocally benign – the ‘common sense’ view – Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky, in Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of Mass Media, suggest that the media serve elite interests. Like a mirage on the horizon, mainstream media provides the illusion of freedom of thought and debate within a desolate civil society. The press integrates the populace into capitalist, institutional structures by indoctrinating individuals with the necessary values and codes of behaviour. This requires systemic propaganda.

Herman and Chomsky outline a “propaganda model”, detailing five inherent traits in modern media structures – ownership, advertising, sourcing, flak and anti-communism. They argue that ever-expanding media conglomerates, clasped tightly within the fists of a few wealthy families and advertisers, have hijacked public discourse. The media, kow-towing to commercial interests and PR hostility from well-resourced elites, adores sensationalism. This increases circulation and profit. Think clickbait listicles from Buzzfeed, news anchors yelling at interviewees and televised meltdowns. This is the modern media landscape.

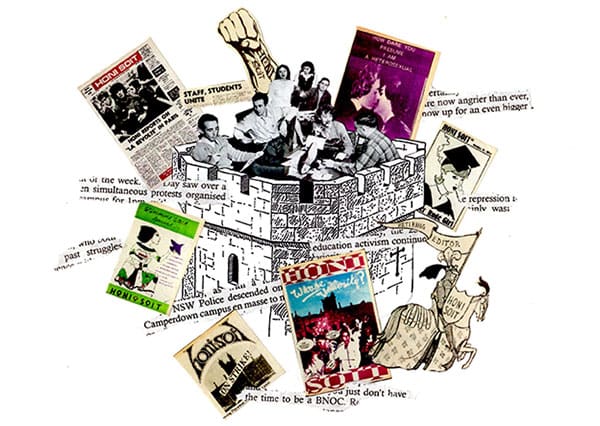

Many (leftists) therefore view student media, a subset of independent media, as an El Dorado – a hidden city resplendent in gold, free from the greed of capitalist invaders. Honi Soit undoubtedly does function like this, launching frequent skirmishes outside the city walls against powerful entities. But it is also true that Australian student media – Honi in particular – is not entirely separate from mass media, free market dynamics and capitalist relations of production.

That’s not to say that Honi doesn’t push boundaries. Honi has a flat organisational structure and an egalitarian ethos. No boss looms over us. Each editor largely has equal say and each week a different editor functions as the editor-in-chief (EIC). Besides writing the editorial on page 2 and guiding a couple of minor design decisions, the EIC role is little different from a normal editing role.

As part of our working agreement, we, like previous teams, have a 7 person majority for decision-making. Maani Truu, an Honi editor in 2017, explains: “in worst case scenarios that led to discussions that went on all night over a small thing… In the best case scenario, that led to really invigorating debates… There was inevitably someone else on the team who disagreed and they would want you to answer to that… As a temporary experience it was really enjoyable. It was what you imagine university to be like – really robust debates and lots of crazy ideas.”

As a weekly publication, Honi presents promising possibilities. While it’s more news-focused than other student media, it has a capacity for introspective, analysis pieces – or “slow journalism” – from students frequently engaged in cutting-edge, radical thought. As Herman and Chomsky detail in Manufacturing Consent, sourcing is a key issue within mainstream media. In fast-paced newsrooms, journalists rely heavily on ‘credible’, official sources. They attend court hearings and police departments. They skim-read press releases and draft legislation. They return to well-trusted, proven leaks. This minimises the cost of investigating and fact-checking, and allows fewer journalists to monopolise news production. Their reporting usually therefore replicates ruling class narratives. Student journalists, by contrast, tend to bypass the structural issues that shape mainstream media.

With freedom to experiment – unlike most newspapers Honi has a creative and comedy section and most editing teams are not smitten with objectivity – students often provide counter-hegemonic narratives. Former Honi editors Michael Richardson and Julian Larnach (2011) believe it’s precisely this snarky and irreverent tone which distinguishes Honi and makes hard-hitting journalism possible.

Furthermore, Honi is a weekly, printed broadsheet, and thus unique among Australian student media. Regarding student culture and the onslaught on tertiary education by successive governments, Michael remarks that it’s as if “the music has stopped and everyone is scrambling for a chair.” He believes that, despite the newspaper’s issues, it is worth protecting because there is a “tangible connection” to USyd when you have a physical copy in your hand.

When you recognise that reading in print is more immersive and linear, you realise that Honi has a dedicated readership and the ability to expand minds in ways that advertisement-laden, hyperlink wormholes do not. Researchers Neil Thurman and Richard Fletcher have charted the decline in engagement with British publications which move to a purely online format across a number of years. They found, for instance, that audiences spent time perusing the British newspaper The Independent 81% less in the year following March 2016, when it became online-only. Framed in this way, we can view Honi as the vanguard of a possible print revival; a blueprint for the future.

* * *

The suffocatingly-massive elephant in the room is accessibility. Privilege is everywhere and unmissable. It presses you into a corner and sucks all the air from the room. See, despite the rich history of Honi editors fighting for workers’ rights in other industries, there has been little self-reflection, at least publicly, on our own (poor) working conditions and the ways in which Honi reproduces hierarchies of power.

As a near unpaid internship, which lasts far longer – 12 months – than your average internship, the pay rate locks out lower SES students. No wonder then that the vast majority of Honi editors come from a small crop of elite private schools. Toiling away for what equates to roughly $3 or $4 per hour – there is a stipend of $4400 for each editor – entrenches a culture of privilege, like all unpaid internships, where positions are generally only accessible to those leaning on families for financial support or those in no rush to finish their degree. This often means losing the benefits of studying full-time (Centrelink benefits and a concession opal card).

This situation mirrors the entrenched underpayment of writers within a neoliberal society. Writing industries frequently outsource labour to unpaid interns and freelancers. The 2015 Interns Australia Annual Survey found that internships were more common in media and communications (23.43 percent) and the arts (15.7 percent) than in any other industry.

Just this year, Fabian Robertson exposed in Honi the exploitation of unpaid interns working for the Australian lifestyle magazine Offspring. Trawling through the Facebook group Young Australian Writers reveals a whole host of horror stories, from freelancers never receiving promised payments to casual journalists being overworked to young writers having their words plagiarised.

But the stipend for Honi editors is also symptomatic of funding issues for the USyd Student Representatives Council (SRC), which receives just over $2 million in funding from the student services and amenities fee – that small additional fee of $150 or so you pay each semester. The University of Sydney Union and Sydney University Sport & Fitness, meanwhile, receive roughly $5 million in funding, and they have consistent sources of revenue. Aside from advertisements in Honi, the SRC does not produce any revenue.

The lack of investment in student bodies is, of course, a structural issue within capitalism. Voluntary student unionism, corporate university business models and funding cuts to higher education stem from the neoliberal infatuation with the economic value of, and marketability of, knowledge. This system legitimises and funds pursuits such as technological innovation, medical research, weapons manufacturing and the mass production of pharmaceuticals because they support the productivity, competitiveness and power of the nation on the global stage.

The arts, meanwhile, suffer. As Michael explains: “Here’s the problem: a 24 page paper requires way more resources than the SRC really has. If you want this thing, it has to come from the passion and the hours and the free labour of the editors. That’s not going to happen any other way.”

Stress and overworking is a shared (read: endured) experience for Honi editors. After grabbing coffees with reporters to discuss pitches, writing your own articles, replying to emails, attending meetings, breaking news, editing work and posting content online, the Honi schedule culminates with the mad weekend scramble to lay up the next week’s print edition on Adobe InDesign. With ten budding writers and stu pol hacks – career paths magnetic to big egos – jostling cheek by jowl within a matchbox-sized office, the atmosphere fluctuates between jovial, tense and deranged. Michael confesses to me a particularly memorable meltdown he had in the office in week 4 of first semester. He says he took the work “way too seriously to begin with.”

“I had been really pushing myself those first four weeks because I was the most technically-proficient. (I’m a programmer now.) I was really getting into the nuts and bolts of all the software we were using and laying everything up. I was coming in and finding that people were not aligning things properly… I realised: who cares? I was setting myself a set of standards that I then quietly held everyone else to – totally unreasonably.”

I too remember reaching a tipping point in first semester. My dedication to Honi was causing rifts in my relationship. Only after talking to my partner and recognising that I was pressuring myself unnecessarily did the job become easier. Put succinctly: I learned to give less of a shit.

Late-night Honi shifts have entered the realm of folklore. Tales of caffeine-fuelled editors pulling all-nighters, tapping methodically on keyboards like woodpeckers drilling into bark, permeate the student-activist population at USyd. Collapsing into a nest of emergency blankets on the office floor, aching for sleep, is like a rite of passage. Some stories are no doubt embellished. But many are entirely based on my own reality.

When Julian describes the intense workload he endured, it all sounds eerily familiar. “We had an attitude where the more hours you could work the better. If you could be there until 4 in the morning [on the weekend], that’s good… The more time you could give to it – even if you weren’t doing any work – was important.”

These last words hit a particularly raw note. Memories flash before me of futilely button-jamming in the Honi office before a frozen SRC computer, vainly hoping that sheer willpower might revive the ever-unreliable, junkyard Mac. With frequent VPN issues – and therefore an inability to work remotely – some Sunday shifts this year have seen only one SRC computer still working and nine of us editors crowding around the one editor lucky (unlucky?) enough to have a functioning machine. The role of the Honi editor, it seems, is to be omnipresent, to create a weekend theme song with pen clicks and finger-drumming. Ingrained in the work culture is the expectation that you want or can sit around an office for hours, depriving yourself of sleep, even when you have no tangible way to contribute to laying up and no easy way to get home at 2 AM, Monday morning.

Embedded within Honi’s work culture, and passed on almost as a cultural legacy, are bourgeois traits – hyper-competitiveness, intense productivity and social capital. The better connected you are the more likely you’ll be useful to Honi. Integral to editing the paper is a desire to one-up previous editing teams and to break university-related news before our public broadcasters and the Murdoch press juggernaut.

Since there is a turnover in staff every year, the expectations and workload threaten to become bigger as every term passes. Indeed, Honi’s online presence was practically non-existent when Michael and Julian edited the newspaper in 2011. In recent years, teams have begun publishing content online from December, when they cover NatCon, and intermittently during January, instead of beginning with the O-Week edition in early February. Is it the case that Honi editors put in more hours than ten years ago? Quite possibly.

Asserting that it’s up to individual team members to decide how hard they work is a cop out when the toxic work culture is an historical and structural issue. Since Honi has a trend-setting function in Australian youth culture and employers revere Honi editors, the newspaper has the capacity to normalise poor working conditions for aspiring writers. To get a leg-up in a capitalist society which undervalues writing as a skill, working your socks off for a negligible wage is perceived as necessary and acceptable. We must critique and dismantle this view.

Social capital is the fuel that drives this thirsty engine of student journalism. To even become an editor, candidates must undergo a gruelling election campaign. Personal reputation and the institutional power of well-established political factions hold particular sway in this process. This election process drags Honi into a cut-throat student politics world, perceived publicly as centring career advancement and CV-stacking as much as worker solidarity and alliance-building.

Maani dedicated much of her time as an editor in 2017 to illuminating structural inequalities at USyd. In one iconic article she argued for the abolishment of Honi elections. On the phone to me, she asserts that student elections are “not particularly effective at engaging students outside of a pretty niche bubble. That’s why we see the same faces often popping up in multiple roles over many years.” Michael, meanwhile, suggests that the election is a “fucking nightmare” and “a little comical.”

“If your goal is to make a student-focused and student-voiced paper, I don’t think you necessarily get that by going up to some second year with their AirPods in, harrying them as they’re walking down Eastern Avenue.”

* * *

At a time when the cost of journalism, arts and creative writing degrees are set to double, it is more important than ever that we make Honi more inclusive. If neoliberal models for higher education, centred on the employability of students and profitability, persist worldwide, journalism will remain an elite pursuit. As Maani says: “The benefits [of Honi] don’t just stop when you stop editing Honi… having that on your resume or just being able to point to stories that you wrote during the year, if you want to continue a career in media, is really invaluable… We really need to diversify the people getting into student media so we can also diversify the people moving into mainstream media.”

When I chat to Julian, he quips, quite eloquently: “Student journalism is a protean form of journalism trying to figure out what it is while the writer is trying to figure out who they are.” Part of this self-discovery process involves honest self-reflection and acknowledgement of my own racial and financial privilege, which locks out those less fortunate than myself from future career prospects.

In 2016, Maani campaigned on the basis of bursting the Honi bubble with a nail gun. She wanted to see more regional, international and first-in-family students contributing to Honi. This was a personal crusade. Maani always felt “less worthy to be an Honi reporter or to be in student politics” because she grew up in the Central Coast, did not attend a private school and did not grow up amid obscene wealth. She wanted “to put the ladder down for other people in a similar situation”.

In the editorial for the last (serious) edition of Honi in 2017 – Honi’s last edition is always a satirical edition – Maani recorded an admission of guilt. She felt that the team had failed to bring more diverse voices into Honi. “Rich kids already have the world at their feet – don’t let them have student media too.”

Three years later and nothing has changed. This time it’s on all of us.