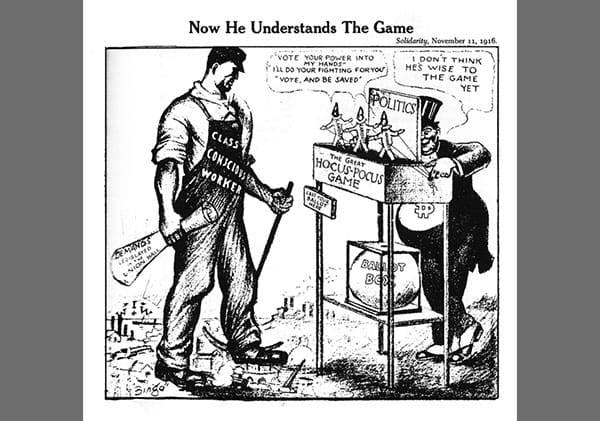

As we approached the US presidential election, calls to “vote so we can beat Trump” were widely voiced, maintaining the liberal electoralist doctrine that no matter how bad the evil, voting will save you. However, laments about the lack of real choice in the electoral system resonated with people on a level not seen before as the failures of modern electoral democracies become clear.

While our Australian system differs slightly, the theme is familiar. So disillusioned are we with politics in its current form that “playing politics” is an accusation politicians themselves use against each other. Corruption scandals come and go to lazy eye-rolls from a populace too used to dishonesty and self-serving MPs to expect anything else. Solutions are intermittently suggested: restrict political donations, royal commission into x, vote below the line, vote for minor parties, etc. Whether the electoralism that is the backbone of so many modern “representative democracies” is inherently flawed is rarely questioned.

Firstly, let’s consider the electoral process. The logic goes thus: a populace has the right, every x years, to elect representatives to the government which embodies the state. This populace is therefore governed according to their wishes, since no one would vote against these wishes (theoretically). If a government performs badly, a better candidate will be chosen; if it performs well, it will be re-elected. This logic has many flaws, though I will concentrate on one problem: the election itself. In this system, the entire political force of the populace is concentrated to an extreme degree into one specific element: the election day ballot. In the ballot, all a constituency’s grievances, ideas, and opinions are neatly reduced to two pieces of paper. When citizens cast their vote one day in every 1065, huge errors of governance and corruption scandals become one issue out of many. Even if seething with hatred at one party or candidate, one may feel compelled to vote for them if the other option isn’t up to scratch.

To be sure, grievances can be aired outside of election cycles. There may be letters to MPs and consternation in the media. What the ballot does, however, is distil these political rumblings into a singular element that, being so concentrated, is easily manipulated by political, social, and financial capital.

Another flaw of electoralism is its function in legitimising the state and the reigning government. With the vote being the only “legitimate” political action recognised by the state, all other forms of politics including direct forms such as protest and striking, are discouraged. Under electoralism, protests only serve the purpose of airing grievances, while strikes are simply a special way of getting a pay rise. The modern liberal democratic citizen would barely consider taking these actions and if they did, it would only be with the goal to encourage (not force) the state and capital to make changes. The benefits of society thus become gifts from the state. JoFry and Scomo brought the economy “back from the brink,” not the millions of workers who produced that wealth. Welfare payments and health services are “delivered” by the relevant ministers, not by individual health and social workers. The relationship is one of dependence – who will guarantee your government subsidies, your health benefits, your work rights if you don’t elect me?

The introduction of electoral democracy had a stultifying effect on the populace and popular movements. When the state extended this privilege to the people, direct action against the state was appropriated into elections. Instead of occupying streets in protest at a politician, simply vote them out! Instead of legislating working conditions in a union hall and striking, vote for the Labo(u)r Party, we’ll get those conditions for you! While it is good that better conditions are won for workers and citizens, the Italian anarchist Errico Malatesta notes that these “can and must be obtained by the workers themselves” through direct action which, unlike electoralism, develops in each individual worker a “consciousness of their own rights.”

The flaws of electoralism considered, we ought to question the need for politicians at all. The current justification is that politics is a special ‘job’ that needs doing. If we suppose that the politicians carry out some sort of labour, it follows that election day is one of the greatest instances of outsourcing labour in our society. In representative democracies, the logic is that the citizens are individually too busy or too lacking in the relevant expertise to manage the state and society. Thus, they give that job to a politician by electing them to represent their opinions and ideologies within government. Questions ranging from on whom we should wage war to if hospitality workers ought to get compensated for working on weekends are all outsourced to the government and the MPs that comprise it.

This logic is acceptable if we suppose that the “political labour” undertaken by these politicians ought to be removed from the hands of the citizen to the abstract entity of the state. However, politics is everyone’s business; perhaps more importantly, the governance of one workplace or community is the business of the individuals that comprise that workplace or community.

We only have to critically regard the current system to see this concretely. Contrary to the statist myth, Scomo isn’t studying the minutiae of data on Australia’s infrastructure when he announces increased spending for building projects. Health Minister Greg Hunt doesn’t know jack shit about health systems (at least no more than you or me). What these elected ‘representatives’ rely on is advice from local sources. Local communities know how much they need a new road, individual registrars and nurses can tell you how many beds are available in a given hospital. Ordinary citizens, in coordination with one another, are the ones who manage society day by day.

Given this, the legitimacy of politics as a special profession (and, by extension, the idea of the state) is dubious. The idea of professional politicians is even more odious when we give even a cursory glance at our “representatives.” From shitty advertising execs to failed furniture importers, MPs are generally not geniuses who have risen to the parliamentary chamber through a genuine connection to local constituencies. Instead, they are largely chosen through complex pre-selection processes which prioritise connections to financial and political capital and which even officials from the major parties in the US would envy.

Beacons of hope seem to emerge from electoral politics from time to time. Social democrats find solace in the re-election of Jacinda Ardern, for example. Upon further analysis many criticisms, such as Ardern’s inability to address growing inequality (up from when she attained office) and to remedy the effects of austerity measures on New Zealand’s schools and hospitals, can be made. Accepting her successes (real or perceived) uncritically belies the deeper problem with electoral democracies that is leader reverence. Similar to the way in which one may “thank” Scomo for leading Australia through COVID-19, New Zealand’s collective successes are laid at the feet of a beaming Ardern. Again, this neglects the part played by workers and citizens in the management of society. Not only that, it allows the systems and institutions which the state represents (such as capitalism) to be presented with “a human face,” in the words of former Deputy Prime Minister and NZ First leader Winston Peters, blunting any critiques of said systems. Furthermore, these arguable successes of electoralism are infrequent and idiosyncratic. Indeed, their rarity in electoral democracies itself shows the inefficacy of electoralism in achieving fundamental change. Finally, the idea that we must wait around for a saviour-politician reveals the level of powerlessness to which electoralism has brought us.

This critique doesn’t necessitate abstentionism, nor does it deny the importance of democratic decision-making. What it questions is the viability and legitimacy of electoralism as a method of political action. The state and capital are the sole purveyors of “democracy” in the modern world; we won’t rid ourselves of them by voting within such “democracies.”