One of the first stories I ever heard about Honi Soit was a bizarre tale of censorship. In 1979, Tony Abbott was President of the Students’ Representative Council (SRC). The story goes that Liberals on campus would request archived editions of Honi Soit from the Rare Books section of Fisher Library. Then, they would cut the pages out of them, graffiti over them, and tear them up. There are even rumours of Honi pages churning in the stomachs of prominent parliamentary Liberals.

In a trip to the New South Wales State Library, I hunted down editions from Abbott’s tenure and was met with exactly what I had expected — torn out parts, missing pages, and blacked out names — but sadly no bite marks. It was impossible to imagine that the missing sections could have possibly been worse than what remained — Abbott calling to defund the SRC, Abbott saying “too much” money was being spent on education campaigns, and (unsurprisingly) articles about Abbott being a raging misogynist.

It is difficult to deny the power of student journalism on campus. As a historically radically left-wing paper, Honi has played an important role in amplifying student voices against institutional power, oppression, and producing content that challenges readers to consider injustices in the world around them. Such activity has often drawn the ire of right-wing, conservative groups and powerful institutions.

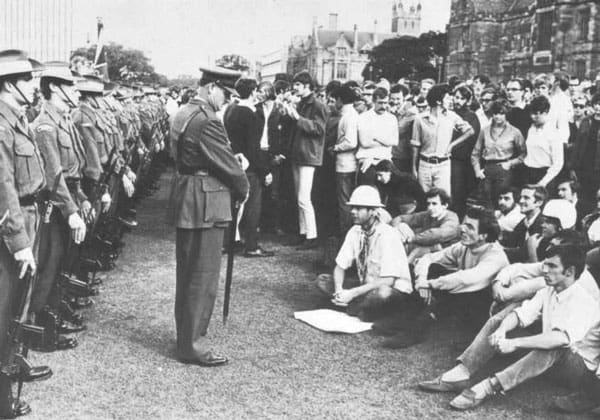

But Honi’s controversial takes have not been bound solely to campus happenings. Honi has also been involved in large scale political movements, playing an integral role in the development of the Anti-Vietnam War campaign in Australia. Blamed for instigating the ‘run the bastard over’ campaign, Honi was described as “filthy and scurrilous” by the Legislative Council of NSW. However, such radicalism was not without consequence. During the 1960s, Honi was under threat with advertisers unwilling to fund the publication and the University Senate threatening to disestablish the paper.

The subjects of controversy have changed radically over the years, from publishing information about birth control in 1945 (a radical move back in the day), to calling for the end of ANZAC Day in 1958, and reprinting the infamous article titled ‘The Art of Shoplifting’ in 1995. In 2013, censorship of Honi Soit made national headlines after an edition known as ‘Vagina Soit’ featured images of 18 vulvas on the cover of the paper. Concerns about the legality of this display led to the printing of black bars over the vulvas. However, when printed, the black bars appeared transparent which led to the subsequent removal of all 4000 copies of Honi from campus.

After extensive debate and compromise with the SRC Legal Service, the paper was returned to campus, and labelled with the same R+18 rating found on pornography. This was ironic, as the cover, and its corresponding feature ‘The Vagina Diaries’ aimed to de-stigmatise and de-sexualise the vulva.

“Either accept vaginas as normal, non-threatening, and not disgusting, or explain why you can’t,” wrote the 2013 editorial team. “Here they are, flaps and all. Don’t you dare tell me my body offends you.”

Honi Soit was founded in 1929 to provide a counterbalance to the critical portrayal of Sydney University students in mainstream media, creating a platform for student voices. Since then, Honi has grown into many different things: it is a time capsule for student life at USyd, an independent voice in an increasingly profit-driven media landscape, and a forum for the exchange of diverse perspectives.

For decades, student journalism has also served to expose the horrors that lurk beneath the surface of an otherwise innocuous campus, including the ongoing culture of sexual assault, hazing, sexism and racism at USyd’s residential colleges. An Honi expose of hazing and excessive drunkenness at the colleges in 1952 was met with uproar from the colleges, resulting in a particularly notable incident that saw a group of college students chasing a truck carrying copies of the edition out of university grounds.

In more recent years, student journalists have kept the fire lit under the colleges, often in collaboration with the Women’s Collective. Pulp Media reported on a publication by Wesley College students from 2014, wherein a section titled ‘Rackweb’ detailed inter-college hook-ups, and awarded titles to students like ‘Best Ass,’ ‘Best Cleavage,’ and ‘Biggest Pornstar.’ Six days after the story broke, then-SRC Women’s Officer Anna Hush led a silent protest at Wesley College and demanded it publicly release the names of the editors of the college publication and introduce mandatory sexual harassment education.

In 2020, Honi uncovered a raft of allegations of ongoing racism, sexism and acts of hazing at St Andrew’s College. Soon after the article was published, the Women’s Collective organised a protest outside St Andrew’s College. Speakers called to repurpose the colleges and turn them into safe, affordable student housing. 2020 Women’s Officers Vivienne Guo and Ellie Wilson told Honi: “The elite residential colleges have never changed or improved, they have only gotten better at hiding the violence under the surface.”

Of course, the colleges are not the only bogeymen to haunt the campus. In 2019, editors of Honi published an expose of an Neo-Nazi network on campus, involving members of the Liberal and National Parties. The investigation detailed years of evidenced Neo-Nazism on campus, from sieg heil salutes in student debates to reports of a student singing ‘He’s A Pisspot’ and toasting Hitler in the middle of a lecture. A week later, the Autonomous Collective Against Racism (ACAR) responded to the investigation with a rally on Eastern Avenue that pushed back against covert forms of racism on campus. Protesters carried a banner that read: “Fuck Nazis, smash the fash.”

In publishing content that challenges injustice, it is unsurprising that student journalists are often at the center of widespread controversy. In 2018, Women’s Honi drew international controversy with its front cover depicting Palestinian freedom fighter Hamida Mustafa al-Tahir with a rifle in her hand. While this cover drew ire from organisations such as the Australasian Union of Jewish Students (AUJS), then-Women’s Officers Madeline Ward and Jessica Syed noted that al-Tahir’s actions occurred in the context of war. “We believe in and support the right for people to resist occupation and oppression,” they wrote in a statement.

Today, student media continues to platform voices which are often locked out of mainstream media, holding powerful institutions and individuals to account. 2020 was a year of unparalleled chaos. During the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the University pushed ahead with a lengthy agenda of austerity measures, aiming to cut innumerable staff and courses; they were met at every turn by student journalists who shed light on the unscrupulous actions of University administration. The efforts of student media sparked heated dissent from the student and staff community at USyd, leading to months of protests that saved many jobs and courses from the chopping block.

Organisations like the University of Sydney Union (USU) came under heavy fire after it suffered heavy losses at the hands of the pandemic, thus hoping to justify the quiet laying off of all casual staff and several of its full-time staff. The USU’s efforts to profit from the health and financial crisis of many of USyd’s students through overpriced grocery boxes were also criticised in an article by 2020 Honi editor Madeline Ward who wrote: “the grocery boxes are a product of an organisation run by a board of bourgeois idiots.”

Student journalism is often not safe or comfortable work. With the Black Lives Matter movement and education activism coming to a head, Honi reporters regularly found themselves in the thick of police violence, risking arrest and heavy fines. Yet, student media have managed to capture snapshots of a university community under siege: students slammed with arrests and tens of thousands of dollars in fines at education protests, hundreds of students sprinting across Victoria Park to avoid being crushed by police horses, and the forceful arrest of law professor Simon Rice which made media headlines across the country. Yet, as it often does, student journalism coloured in the gaps left by mainstream media, documenting a vibrant year of student protest.

Engaging with student media provides another way for students to practice their activism. Those who can’t attend protests are able to draw attention to the issues that matter to them through their writing and art. In addition to independent investigations and news reporting, Honi has often published anonymous letters and tips, many of which have pierced the veil that protects the most privileged individuals at USyd. For example, a letter to Honi in 2012 drew attention to a racist ‘British Raj’ party hosted by St Paul’s. The event spurred think pieces across campus and in mainstream media, provoking national debate about the racist culture within Sydney’s colleges.

The future of student activism is bright, and student journalism will always have a role to play in upholding a proud tradition of protest and revolution. Just last year, student activists occupied the F23 building for almost 6 hours, a physical demonstration of campus discontent in a year defined by physical separation. The occupation that took place spontaneously after an NTEU rally was covered by Honi which then ignited a wave of solidarity and saw more students flood into the administration building. Student media, such as the likes of Honi Soit and Pulp Media, are vital records that hold future political leaders to account and their editorial independence is as critical as that of the mainstream media.