Sometimes, the only way to repair the machine is to break it. The Art Gallery of NSW is screening two incendiary masterworks of radical cinema as part of the Japan Film Festival: Matsumoto Toshio’s feverish exploration into the LGBT underground of 1960s Tokyo, Funeral Parade of Roses (1969) and Tsukamoto Shinya’s break-neck industrial fable of flesh being fused with metal, Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989).

The animosity towards ‘respectable’ style shared by these two films is well-founded. Unfortunately, the vast majority of commercial cinema is born from capitalist mega-conglomerates, creating an endless stream of disposable media. Popular films use a grammar that reduces signifiers of reality to a strict patriarchal and heterosexist hierarchy of images that saturate the visual domain, devaluing transgressive art forms that do not sustain the dominant order.

For filmmakers who seek to find new modes of expression, this system is a tumor on the medium. How can you create new art when the language you use is so deeply commodified? In his book Tokyo Cyberpunk: Posthumanism in Japanese Visual Culture, Steven T. Brown wrote: “This new path, in its combination of incongruous categories, may come across as perversely monstrous, but such monstrosity also holds the promise of transformed identity and new modes and possibilities of experience.” When you break the traditional language of cinema, the cemented hierarchy of images goes with it.

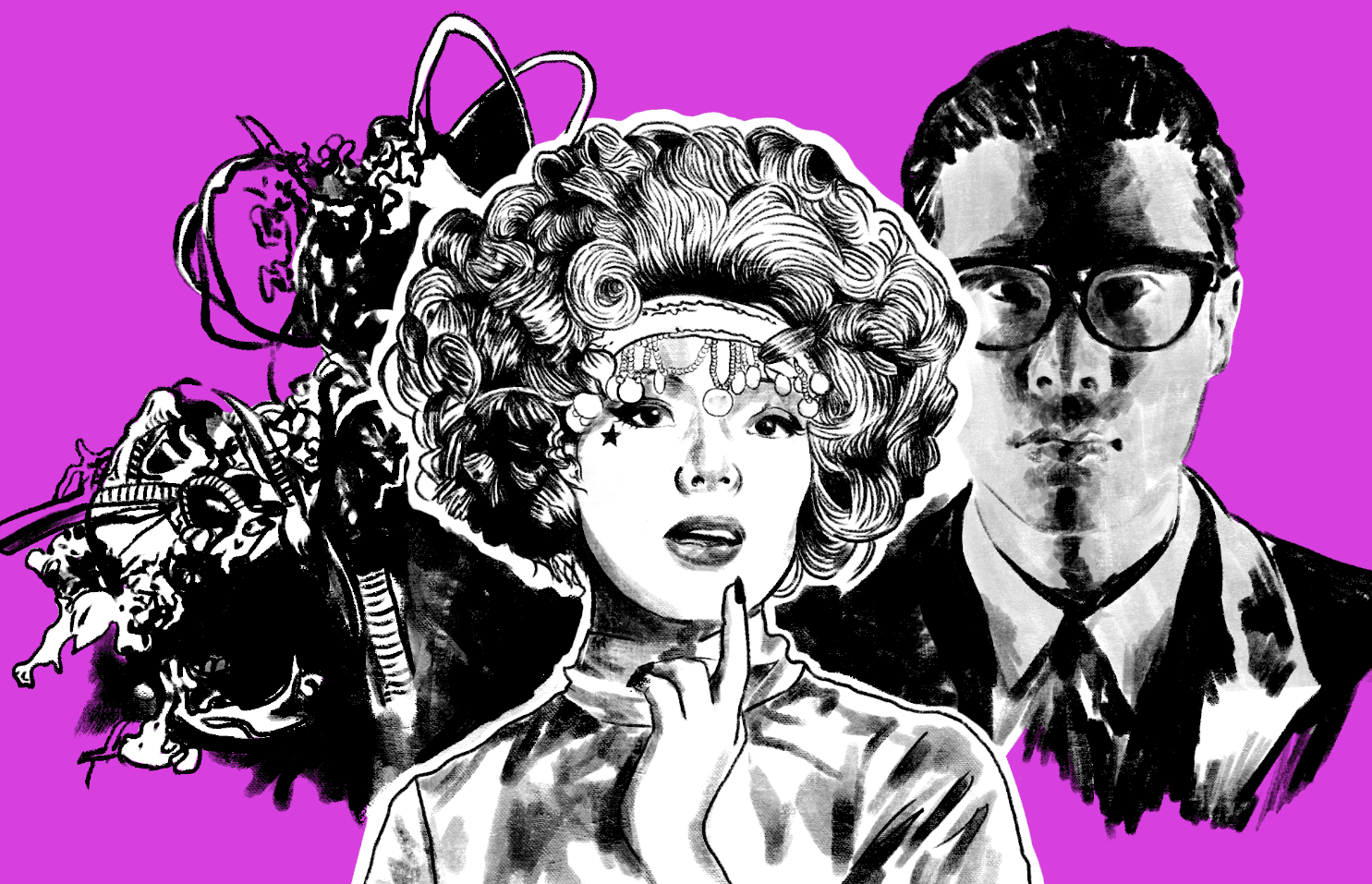

Funeral Parade of Roses follows Eddie, a young trans woman, through a world of bedrooms, street protests and various ‘gay boy’ clubs (a blanket term used in Japan that refers to anyone in the LGBT community). Sampling freely from all corners of commercial cinema, Matsumoto’s debut feature gleefully creates a Molotov cocktail of clashing styles. On a scene by scene basis, the film shifts from documentary, melodrama, comedy and loose retelling of the Greek Tragedy Oedipus Rex. Matsumoto effectively creates an onscreen world that is always shifting, constantly breaking down and re-forming itself. Any points of reference that an audience could hold onto, when they do appear, come malformed and unfamiliar. The result is that you’re never fully allowed to lose yourself in the world, constantly reminded of the malleability and constructedness of the form that you’re watching.

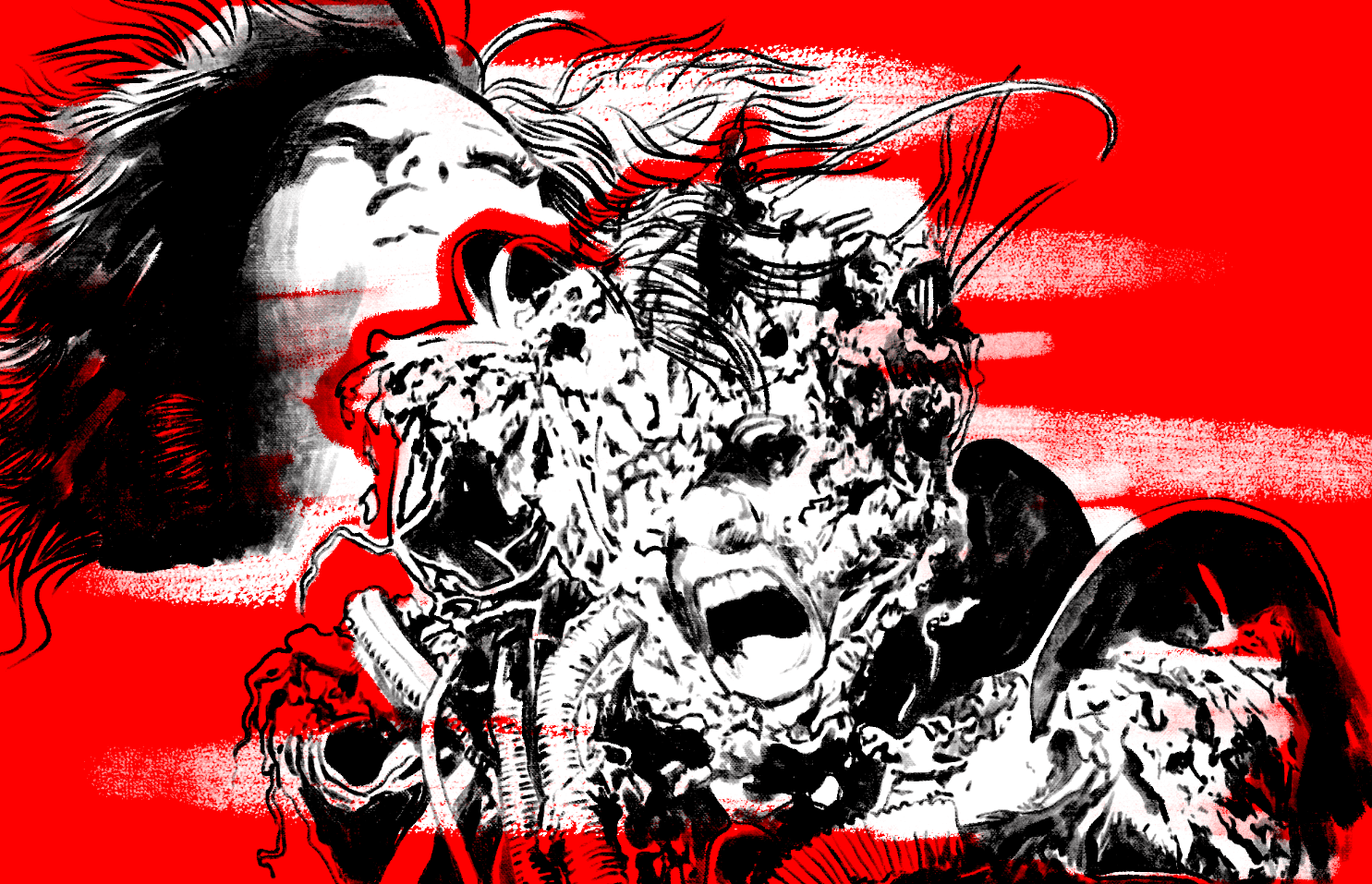

Taking a decisively more violent approach, Tetsuo follows a Salaryman who begins to experience industrial mutations to his body after accidentally hitting a screaming, bloodied man (called“Metal Fetishist” and played by the director) with his car. Tsukamoto uses a feverish blend of high contrast 16mm photography, nonstop montage editing and a teeth-grinding electronic score to break down the barrier between subject and spectator.

The world of both films seems to be on a precipice, ready to collapse at any given moment. Released in 1989, shortly after years of economic inflation caused the price asset bubble over Japan to burst, sending the country into a recession, Tetsuo quickly grounds itself in the wasteland of a failed system. Through a haze of subway tunnels and dilapidated apartment blocks, we watch as gears meld into the Salaryman’s face, wires overtake his veins, and his feet transform him into rocket blasters propelling him around the city. Opening with an image of the Metal Fetishist slicing open his leg and forcing a large metal rod into the wound, it becomes quickly apparent that Tetsuo makes audiences physically aware of themselves. All aspects of the film work in confluence to create a style so direct and affecting that, as Tom Mes put it in his biography of Tsukamoto, it “[gains] a narrative function.” Tetsuo shatters your preconceptions of cinema by turning pain into pleasure, flesh into metal and form into content.

One particular scene in Tetsuo that stands paramount is the scene where, triggered by lust in the heat of his transformation, a power drill replaces the Salaryman’s penis. In transforming the phallus into such a blatantly destructive force, Tsukamoto essentially takes a cornerstone of film language and reframes it as something potentially deadly. Due to the directness of the film’s approach, the emasculation of the Salaryman simultaneously takes away the power from the male gaze that permeates the overwhelming majority of cinema.

One of the most daring experimentations of Roses comes from its blurring of the line between lived experience and fiction. Many of the most dramatic scenes throughout the film are immediately juxtaposed by verité-style interviews with the actors reflecting on the scene. This choice is especially significant given the presence of the cast in the ‘gay boy’ subculture; these are people that have been erased from much of the history of cinema, and yet here they are, speaking directly to the camera about their experiences. The cast’s marginalised voices become as central to the voice of the text as Matsumoto’s.

Both films walk in opposite directions on the same tightrope between transcendence and self-destruction. Roses, opening in an all-white room as Eddie passionately makes love to an older man, begins as a pure statement of ecstasy, while the Metal Fetishist’s self-mutilation at the start of Tetsuo functions as a pandora’s box through which the chaos of the remaining film unfurls. Both characters are living out their fantasies, lost in their own interior worlds of boundless possibility, no longer constrained by the systemic forces at work.

Though made thirty years apart, both Roses and Tetsuo show what is possible when you push a medium to its limits. It had to have helped that this was both Directors’ debut feature, the product of two angry youths dissatisfied with what they saw. The genius of these two films is in how they not only build a new language of cinema, but do so out of the ashes of the previous one; Taking the towering force of capitalism and manufacturing something transformative and personal.