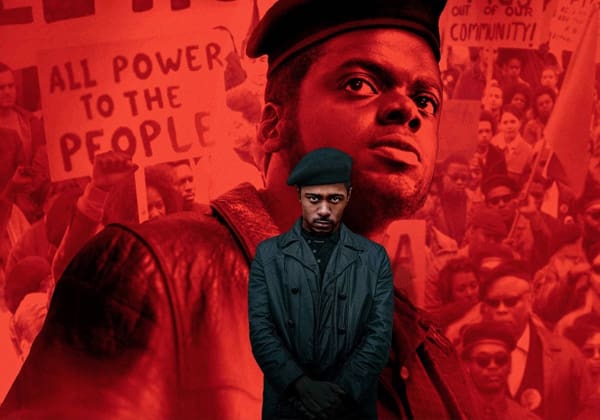

If you hadn’t heard of director Shaka King before his bombastic entrance onto screens after Sundance, you’re probably not alone. With nothing more than a handful of short films and a stoner comedy to his name, he may not seem like the best pick to handle the biopic of a figure as divisive and powerful as Fred Hampton, chairman of the Illinois chapter of the Black Panther Party. However, armed with explosive performances from LaKeith Stanfield and Daniel Kaluuya, King’s Judas and the Black Messiah packs a punch that will hopefully define King’s blossoming style: heavy, unflinching and utterly electric.

Judas and the Black Messiah also positions itself as an incredibly timely piece, the lack of recognition for Black Cinema in Hollywood having been heavily scrutinised in recent years. More importantly, the film takes a head-on approach to tackling issues of police brutality and institutional racism. This choice, relevant to both the context of the film and our contemporary context, hits with a sharp salience and authenticity. While many monumental figures of black history have been ideologically deflated to suit the needs status quo, Shaka King strives for historical honesty. For King, Fred Hampton’s identity as a Marxist-Leninist revolutionary is not something to be ashamed of.

Judas and the Black Messiah is, from the very beginning, a very crisp and streamlined project. King splices historical footage with the establishing scene in a way that helps his audience understand the background without having to spoon-feed. For many biopics, historical footage can become an overused crutch, but King’s use is thankfully sparing. The cinematography and score are similar to a noir-style murder mystery at many points, a decision that really helps Judas and the Black Messiah stand out in a sea of boringly realistic historical films.

Beyond this, the film’s strongest aspect is by far the performances. LaKeith Stanfield keeps his cards close to his chest in his portrayal of FBI informant Bill O’Neal, distancing his audience from any real emotional attachment. While this may undercut the meaning of his ultimate betrayal for some viewers, it certainly increases the weight of the scenes in which Stanfield opens up. In contrast, Daniel Kaluuya’s charisma as Fred Hampton demands the audience’s attention every time he appears on screen. At many points, particularly in the second act of the film, it feels like King is restricted by the actual history of events, and so, fills in the gaps with some fluffy scenes of characters chatting aimlessly. Unfortunately this does begin to drag for a while, but Kaluuya’s energy should be enough to keep most audiences invested.

The most powerful scene in the film is, without question, the assassination of Fred Hampton. A killing that was at the time declared a ‘justifiable homicide’, King makes certain his audience knows who the villains were. While the scenes that follow aren’t necessarily useless, the film could easily have ended with Hampton’s murder, and left the rest for the audience to find out themselves. The mere fact that King gives Hampton such a flattering image, and his death a feeling of injustice, speaks to his unflinching historical dedication. Hampton was, after all, a revolutionary Marxist, something that Hollywood has steered clear of glorifying in the past.

Many influential figures in the Civil Rights Movement have since been ‘watered-down’, so to speak, chief among them Martin Luther King Jr., the face of the movement. Dr King was, of course, a radical socialist who condemned “the evils of capitalism” being “as real as the evils of militarism and racism”. You wouldn’t know this from Dr King’s growing conservative fan base however, lead by conservative thinkers such as Candace Owens, who claims that contemporary civil rights movements are “moving further away from MLK’s dream”, and Dinesh D’Souza comparing his own incarceration with Dr King’s. The ability of conservative speakers to claim Dr King as one of their own speaks to how far to the right his image has been pushed. The fact that Shaka King had the opportunity to breeze over the more radical positions of Fred Hampton makes it all the more interesting that he didn’t. Instead, King opens with one of Hampton’s most radical quotes: “We’re going to fight racism not with racism, but we’re going to fight with solidarity. We say we’re not going to fight capitalism with black capitalism, but we’re going to fight it with socialism.”

In a cultural and social atmosphere where paying tribute to socialist agitators is frowned upon and discouraged, Shaka King’s portrait of Fred Hampton tells you all that you need to know about his approach to filmmaking. While Judas and the Black Messiah doesn’t earn its length, its powerful cast should be enough to keep audiences invested, and hopefully excited for what Shaka King works on in the future.