When the Soviet Union expanded its industrialisation policies, masses of people poured into cities from the countryside to find work. Between 1926 and 1932, it is estimated that the urban population grew from around 26 million to 38.7 million. But as production grew drastically, living conditions declined. Overcrowding in cities meant that workers were forced to live in unsanitary conditions — in tents, underground dwellings, and makeshift homes. At the sight of this housing crisis, it was clear that new planning approaches to the city were needed.

In the search for a new city plan, the ‘Green City’ competition was announced in 1930. It challenged architects to design a short-term vacation resort connected to Moscow by train line, which would house up to 100,000 people and provide a range of recreational and cultural activities. Once the Green City was constructed, not only would it mitigate the poor health of workers in Moscow, it would also be a model for future urban development.

Many leading Soviet architects, who were long preoccupied with the question of how the new ‘Socialist City’ could avoid the ills of urbanisation — dirt, overcrowding, and exploitation — seized the opportunity to participate. Konstantin Melnikov, for example, envisioned a circular Green City with gardens, recreation halls, libraries and restaurants enclosed by a ring of highways, as well as sleeping quarters located in a forest.

But one architect, Moisei Ginzburg, with the help of his student Mikhail Barshch, went further and proposed the transformation of all human settlement in the Soviet Union. “The Green Cities will eat up additional millions and only bring palliative solutions if we continue on beaten paths,” he argued. Therefore, Ginzburg proposed three radical measures: ban all new construction in Moscow; move all public enterprises away from the city; and relocate the Moscow population along the roads linking the city to the countryside. Moscow would then be turned into a park, becoming the Green City itself.

Ginzburg’s proposal embraced the design theory of “disurbanism.” Led by constructivist theorists such as Mikhail Okhitovich, disurbanists moved towards a critique of the city itself, believing that its defects were so grave that they couldn’t be remedied by simply changing urban design. They believed that the city was created in the interests of the ruling class: industry and services concentrated in one place to increase productivity and profit-gain, leading to inhumane population densities that forced workers into poor working and living conditions. As Okhitovich writes: “The city must perish on the ruins of the capitalist relations of production … As these prerequisites vanish, the city itself vanishes as their product.”

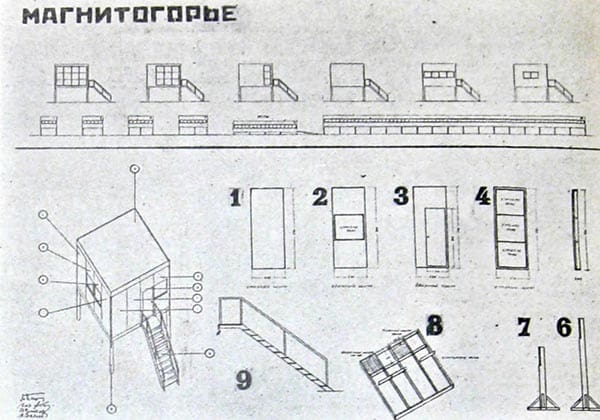

Therefore, dispersing infrastructure across the land and abolishing cities would be the best way to improve living conditions for all workers. They imagined linear ‘cities’ which combined residential, industrial and green zones in ribbons along railway lines, so that all aspects of daily life — living areas, amenities, work, and open space — were located within walking distance.

By eliminating the divide between urban and rural, forcing factory workers and farmers to live and dine together, it sought to remove the inequalities of bourgeois society, and to bring the reality of industrial and agricultural production to the forefront of people’s minds. Linear cities would improve efficiency of production by bringing industry as close as possible to natural resources, and by being arranged according to the natural flow of production. Okhitovich described this as conveyor belt production on a nationwide scale.

Disurbanists also aimed to downscale families, building off Engel’s idea that within a capitalist society, the family unit created the basic framework for the exploitation of women and children by men. Accordingly, they envisioned that people would live in lightweight, individual pods that could be freely joined or dismounted. Sliding partitions could be opened to allow couples to be together, and in cases of divorce, doors could be shut again. Children would be sent to boarding schools and once they matured, would have the right to dissociate themselves from their biological family. By dissolving family life, towns would account for new communal spaces including dining halls, laundromats, and boarding schools.

While the vision for a post-city society was concrete, nothing like it was ever achieved. The disurbanists’ vision of completely transforming human settlements within just a couple of years was ambitious to say the least. Indeed, Stalin dismissed the proposals as utopian experiments that could be economically crippling, and given the technological and material limitations at the time, the disurbanist city may well have been impossible. The Soviet Union reverted to classical urbanism, building hyper-centralist cities with grand boulevards and mass-produced towers not unlike those of today.

Nonetheless, the abandoned disurbanist dream highlights ongoing conflicts in modern urban society; the alienation of the rural working class; humanity’s need to reconnect with nature; the yearning for community one one hand and the need for individual space on the other. While our cities have now become service domains rather than industrial hubs, the defects of urbanisation persist. Because these plans have survived, we can look back on them as testaments to a society that could have been, and with enough imagination, visions of the future.