CW: Graphic mentions of sexual and racial violence.

Camperdown Memorial Rest Park, one of the only green community spaces in an area which has changed its face over decades of gentrification, is in some ways the last refuge of what was once working-class Newtown. The park, which is on Gadigal Country, holds a palimpsest of memories both national and local, visible and invisible, as multi-layered as the dirt beneath the picnickers and dog-walkers who frequent it daily.

Used as a significant social hub with a playground and an open green area holding everything from community gatherings and rallies to the Newtown Festival, the question of crime has long been a defining point in the park’s history. What many of us don’t realise or often forget about the place affectionately dubbed ‘Campo’, is that its historic cemetery enclosed by a high sandstone wall once covered the park in its entirety. 18,000 bodies are buried just below our feet at the centre of life in the Inner West; their headstones and monuments, of which there are only 2,000, have been relocated inside the walls.

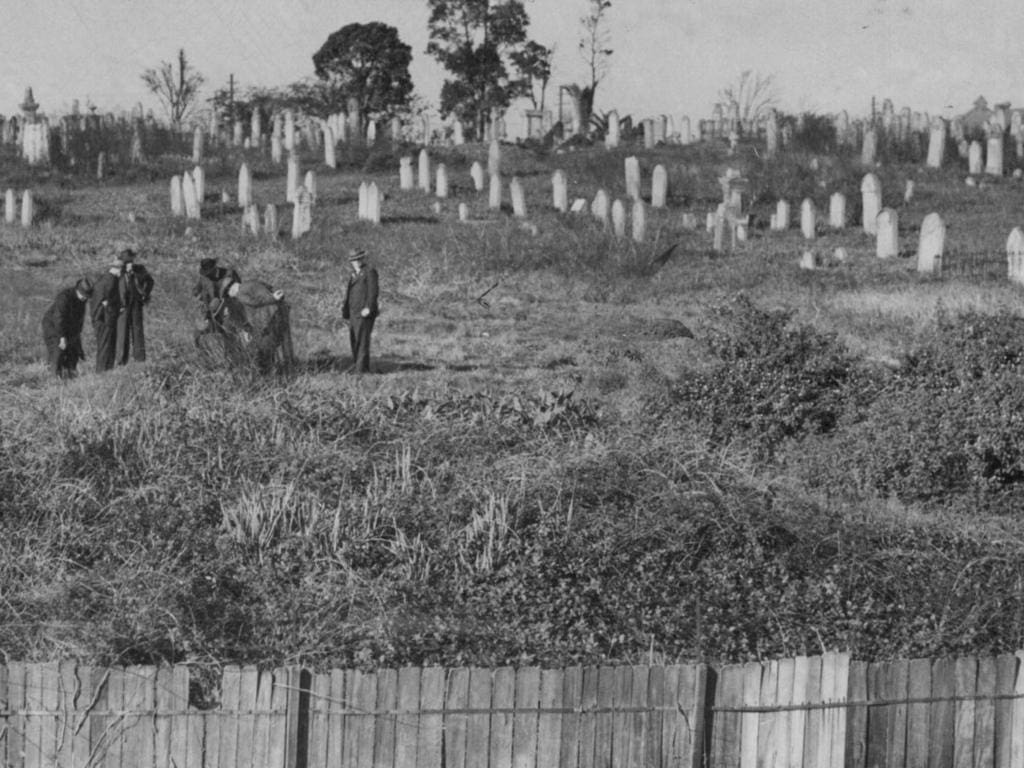

Founded in 1848, Camperdown Cemetery was the main cemetery in Sydney after the burial sites at Town Hall and Central railway station filled up. During the early 20th century, the local council responded to complaints that the overgrown cemetery was a threat to public health by making intermittent efforts at turning it into a park. The proposal was rejected by successive governments and looked upon with scorn by the cemetery’s trustees who were concerned with its historical — and particularly colonial — significance. It wasn’t until 1946, after missing 11-year-old girl Joan Norma Ginn was found raped and murdered in long grass between headstones, that the conversion into a park was finally prompted. News stories from the time provide a glimpse into residents’ views that the cemetery was “a rendezvous for undesirables”, an “uncared for blot on our community” and the “Newtown Jungle”; attitudes which have uncannily re-emerged in the past decade.

When I attend a tour of the overgrown cemetery on a clear Sunday, I am greeted by birdsong and dappled light which dances from grave to grave, filtered through the many trees which have been planted in people’s memory. I notice the locals in attendance exchanging raised eyebrows over teenagers with dyed hair and goth outfits who are having a party amongst the tombstones. As we sit on the 170-year-old roots of the Moreton Bay fig tree at the entrance, a pair of attendees tell the group that they went to school with Joan Norma Ginn’s siblings. “All they talked about was their sister who was murdered, the whole school was fascinated by it.” The woman solemnly recalls the strong impression that a picture of Joan stuck up at Newtown railway station left on her as a child, and how it was later removed during renovations.

In 1948, two years after the murder, four acres were cordoned off for the current cemetery. The above-ground monuments were brought inside the walls and a foot of soil was placed over the site, the bodies left in the ground where the park is today. Archaeologist Jenna Weston tells me the reason not everyone buried in the cemetery had a headstone may be because their relatives were unable to afford one. “The common interments, where the government paid for the burial because the relatives couldn’t even afford that, were not allowed to have headstones… and they were mostly located outside the current wall, on the outskirts of the cemetery.”

While visible monuments give an idea of the wealth of some of the people buried in Camperdown Cemetery, many poor people were put in mass, unmarked graves. Little is known of their lives beyond their names and causes of death. During a measles epidemic in the mid-19th century, there were days where up to a dozen people were buried in communal graves. Sitting in the park with friends, I speculate with morbid curiosity about whose grave might lie just a few metres below us; it’s not easy to imagine death outside the realm of the distant and abstract, even when it is knitted into the fabric of a place.

Wanting a better understanding of whose stories have been remembered and forgotten in the cemetery, I visit Fisher Library’s Rare Books & Special Collections where a disintegrating copy of Prominent Australians and importance of Camperdown Cemetery by P.W. Gledhill is stored. The Chairman of trustees from 1924 until 1962, Gledhill was devoted to the cemetery. It becomes abundantly clear from his foreword alone that the cemetery functioned not simply as a place where bodies were laid to rest, but served an ideological purpose in its commemoration of British colonisers. Gledhill wrote in 1934 that the trustees wished to “safeguard and treasure” the cemetery’s monuments in order to “inspire reverence for those pioneers whose self-denying and courageous exertions securely established the future of our Nation.”

One of the ‘pioneers’ buried in the cemetery is surveyor-general Thomas Mitchell, whose recumbent tomb stands out in an unmarked grassy area and is flanked by a tall iron fence. According to Gledhill, Mitchell’s funeral procession in 1855 was the largest, save William Wentworth’s, that had ever been seen in Sydney. Like Wentworth, who founded the University of Sydney, Mitchell was abhorrently racist. Known for ‘exploring’ the Darling River, Mitchell and his surveying party massacred at least seven Barkindji people on Mount Dispersion in 1836, later describing them as “treacherous savages” in his journal. In the hegemonic narrative of history, Thomas Mitchell is remembered for his “valuable work” as Gledhill describes it, while his involvement in the genocide of Indigenous peoples is either omitted or given little emphasis.

In another section of Gledhill’s book called Early Australians: A Plea for Perpetual Gratitude, Secretary of the British Empire Union in Australia M. F. King writes, “how good a thing it would be to collect the mortal remains [of the pioneers] and inter them in a vast mausoleum in a conspicuous part of Canberra. Quite the next best thing to this would surely be to see that the known resting places of their bodies are preserved for all time as properly cared for shrines of remembrance. One such place is Camperdown Cemetery.”

The excessive nationalistic appraisals of the cemetery — which played a part in the decades-long conflict between the trustees and council over its conversion into parkland — are almost laughable when read in contrast to the current usage of the space. One can only imagine how Gledhill and King would turn in their graves if they saw the political graffiti which emblazons the inside of the cemetery walls, or the swaths of young people who come to the park to drink in preference to the upmarket bars of King Street.

The cemetery’s landscaping and neo-Gothic sexton’s lodge, like the University of Sydney Quadrangle, were designed to have an “English appearance”. Not far from the entrance is a Gothic headstone in memory of colonial architect Edmund Blacket, who designed the University’s main building as well as St Stephen’s, the Anglican church inside the cemetery. The sandstone buildings designed by Blacket needed lime mortar for the laying of bricks, and this was sourced by burning shell middens created over thousands of years by Aboriginal people, recorded to be structures 100 metres wide in some places along the coast. As Peter Myers writes in The Third City, “Sydney’s Second City is probably the largest urban system ever built from, and upon, an existing fabric… directly constructed from the urban structure of a preceding civilisation.”

Perhaps the most frequently visited and largest tomb at Camperdown Cemetery is the mass grave of the Dunbar shipwreck, which is adorned with a rusted anchor. In 1857, the Dunbar was wrecked at South Head during a night of heavy rain and strong winds. Out of the 122 passengers on board, only one survived. A day of public mourning was declared, the city closed down for a funeral attended by around 10,000, and most of the recovered bodies were interred in a single tomb at Camperdown Cemetery. Annual memorial services were held, and the Dunbar took its place in the settler-colonial imagination as a symbol of perseverance. In a 1952 meeting of trustees, Gledhill suggested that an avenue of 24 trees be planted “to the memory of the pioneers of Sydney,” including the Dunbar victims.

If you enter the park opposite from the Courthouse Hotel, you might notice a stone plaque to the right of the footpath. This area is called ‘Cooee Corner’. The plaque is inscribed: “this tree was planted to the memory of Mogo, an Aboriginal who was buried here on 9th November 1850.” Little information is available about the lives of Mogo and the other Aboriginal people buried at Camperdown Cemetery, or why Mogo in particular is commemorated. After the annual Dunbar service in 1932, a pilgrimage was made to the graves of Mogo and William Perry, which were covered with shells from a Pittwater midden. During the memorial service, Dharawal man Tom Foster spoke and played a hymn on a gum leaf. Foster was known as a critic of the Aboriginal Protection Board which was responsible for racist child removals; he later went on to speak on the eve of the first Day of Mourning in 1938.

In The reality of remembrance in Camperdown Memorial Rest Park, Hannah Robinson draws attention to the disparity between the commemoration of colonisers versus Aboriginal people, all of whom, bar Morgo, are buried in unmarked locations in the park. A peculiar ‘Rangers’ League of NSW Memorial’ obelisk sits just opposite St Stephen’s Church as ‘a tribute to the whole of the Aboriginal Race’ according to its inscription. Robinson writes “This baffled me. The state of the monument which had been previously vandalised, and the grouping of Aboriginal people as a collective rather than individually being given burial sites, seemed to contradict this message.”

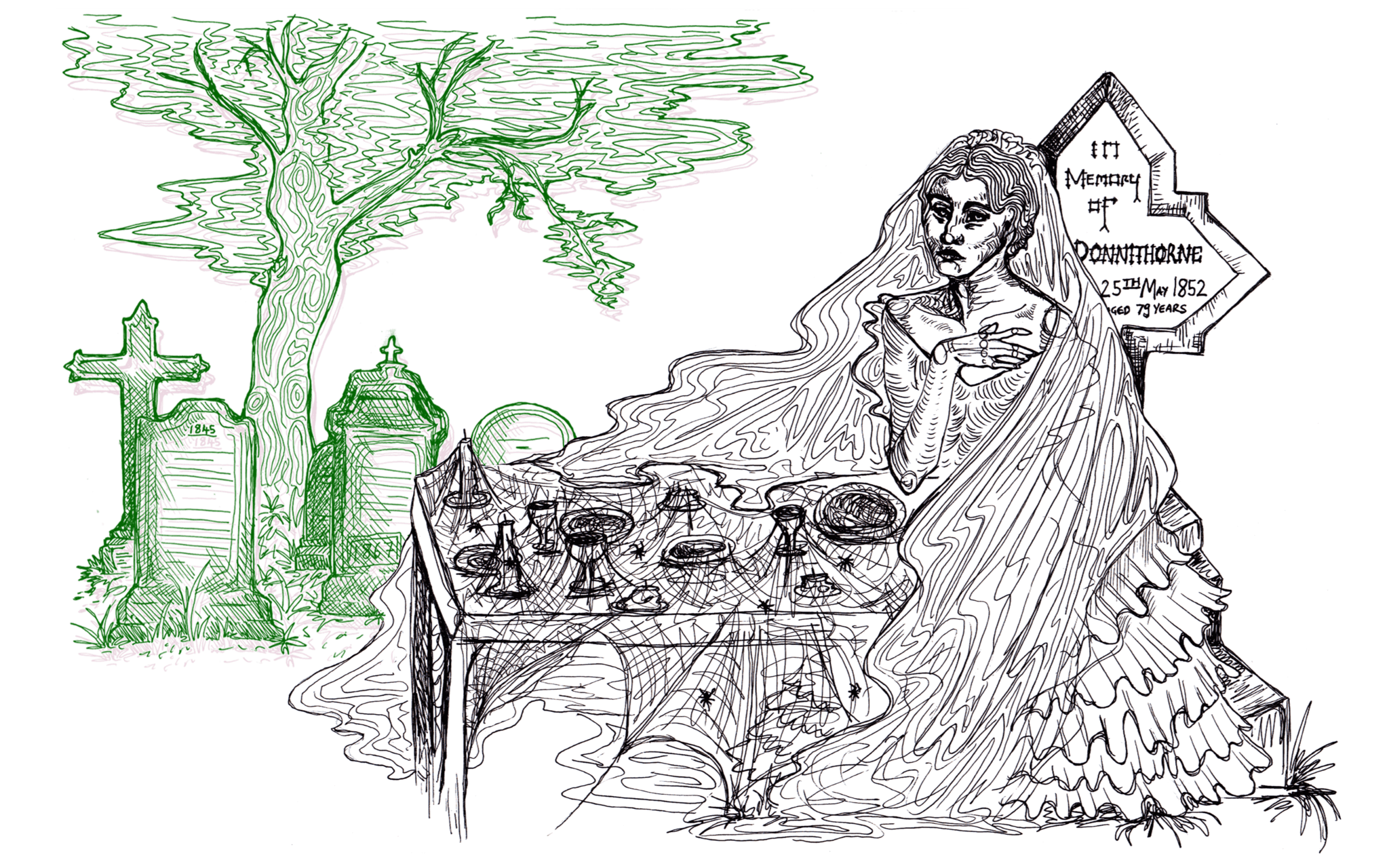

Newtown folk legend holds that the real-life Miss Havisham from Charles Dickens’ 1861 novel Great Expectations is buried in the cemetery. After an English lecture in second-year on the Victorian novel, I recall a friend telling me that the story of Miss Havisham closely parallels that of a woman buried in the park in 1886, Eliza Donnithorne. Donnithorne’s bridegroom was said to have jilted her on their wedding day, causing her to suffer a breakdown and become a recluse at her home in Cambridge Hall, on what is now King Street. The story tells that the wedding breakfast remained undisturbed until after her death, and that all her communications with the outside world were through her doctor and solicitor. The Cessnock Eagle and South Maitland Recorder in 1946 tells that: “When death at last came to Eliza, those who came to carry her to the greater peace of Camperdown Cemetery found her still clad in her bridal gown.”

One theory on how Dickens may have heard the story before writing Great Expectations, proposes that social advocate Caroline Chisholm corresponded with Dickens about it while she lived in the Newtown area. Other historians have suggested that readers of the book in Sydney gradually added details to the urban legend — for which historical evidence is scarce — so that it aligned more closely with the story of Miss Havisham.

Donnithorne’s headstone is located in a shaded part of the cemetery, where an overgrown carpet of English ivy crawls through tombs cracked by tree roots. Constructed from marble and stamped with lead letters, it is clear that the cross-shaped headstone belonged to a family of wealth. We are told on the tour that when the headstone was vandalised in 2004, the UK Charles Dickens Society put money towards its restoration. Gesturing toward a row of headstones opposite the Donnithorne grave which are held up by wooden boards, the guide tells us that because sandstone is easily crumbled by vandals, the cemetery is in a state of “graceful decay.”

In recent years, Camperdown Memorial Rest Park has been the site of increased police presence with residents demanding they put a stop to “anti-social behaviour,” which they say includes underage drinking, drug use, threats of violence, and public defecation after nightfall. A statement from residents to the Inner West Courier complained that “The park at night, especially after 9pm, is being used like a pub”. At the tour, our guide tells us that she often has to pick up condoms and syringes in the cemetery. In April 2016, police set up a command bus with four officers deployed “as a deterrent to any crime that might arise.” From the murder of Joan Norma Ginn to incidents of assault and harrassment today, the actions of the police have done little to deter sexual violence in the park.

On 19th January 2018, a ‘civil disobedience picnic’ with live music was organised by community group Reclaim the Streets to protest against a council proposal to implement alcohol free zones in the space. Reclaim the Streets argued that the proposal would disproportionately target young people, Indigenous people, and the homeless, and that it would have the opposite effect intended since violence in the park was occurring after the alcohol prohibition came into effect at 9pm. The removal of lighting at night to prevent people from congregating in the park has also been criticised as counterintuitive.

The Sydney lockout laws, which were lifted in Kings Cross only this month, have also contributed to a changing cultural scene in Newtown and the park. The laws have been connected to an increase in queerphobic violence as a result of more people heading from the city to the Inner West for nightlife. Many queer people in the area will tell you that they, or someone they know, have experienced harassment and no longer feel safe in Newtown.

The counterintuitive effects of increased police surveillance and laws combined with the gentrification of the area mean that the inclusive atmosphere of Camperdown Memorial Rest Park is under threat. With many who have fallen through the cracks of middle-class Newtown relegated to the park, the use of public space has always been an expression of the community it belongs to.

As I leave the quiet park and re-enter the bustling, colourful streets of Newtown, I think of the thousands of stories buried in this place that have gone unwritten. While I had initially set out to research the stories of people from early Newtown like Eliza Donnithorne whose memories are preserved in the park, what I had not anticipated to learn about this place is how intertwined its history is with that of colonialism and class interest. There is nowhere in this country that is not a deathscape once you scratch below the surface of its monuments.