Strolling down Eastern Avenue, the University is abuzz with life. Seagulls assail students for chips and baguettes, while ibises pilfer the scraps. These are familiar friends, and we welcome them. Yet, if you look closer, there is so much more to be found among the cloisters and courtyards. Over one day, a keen urban biologist could fill a whole notebook with observations. Here are my highlights.

9 am: waterfowl, eels and turtles

We start in Victoria Park. The mighty Lake Northam, Camperdown’s drain, supports a delicate ecosystem among its discarded trolleys and beer cans. I walk straight past the ducks and swamphens, directly to the eels. As a kid, there was nothing better than hand-feeding them with strips of bread, making them lunge for their meal, mouths agape. Sometimes they’d miss. The inside of an eel’s mouth is lined with tiny, needle-like teeth, and they make light work of a 5-year-old’s fingers.

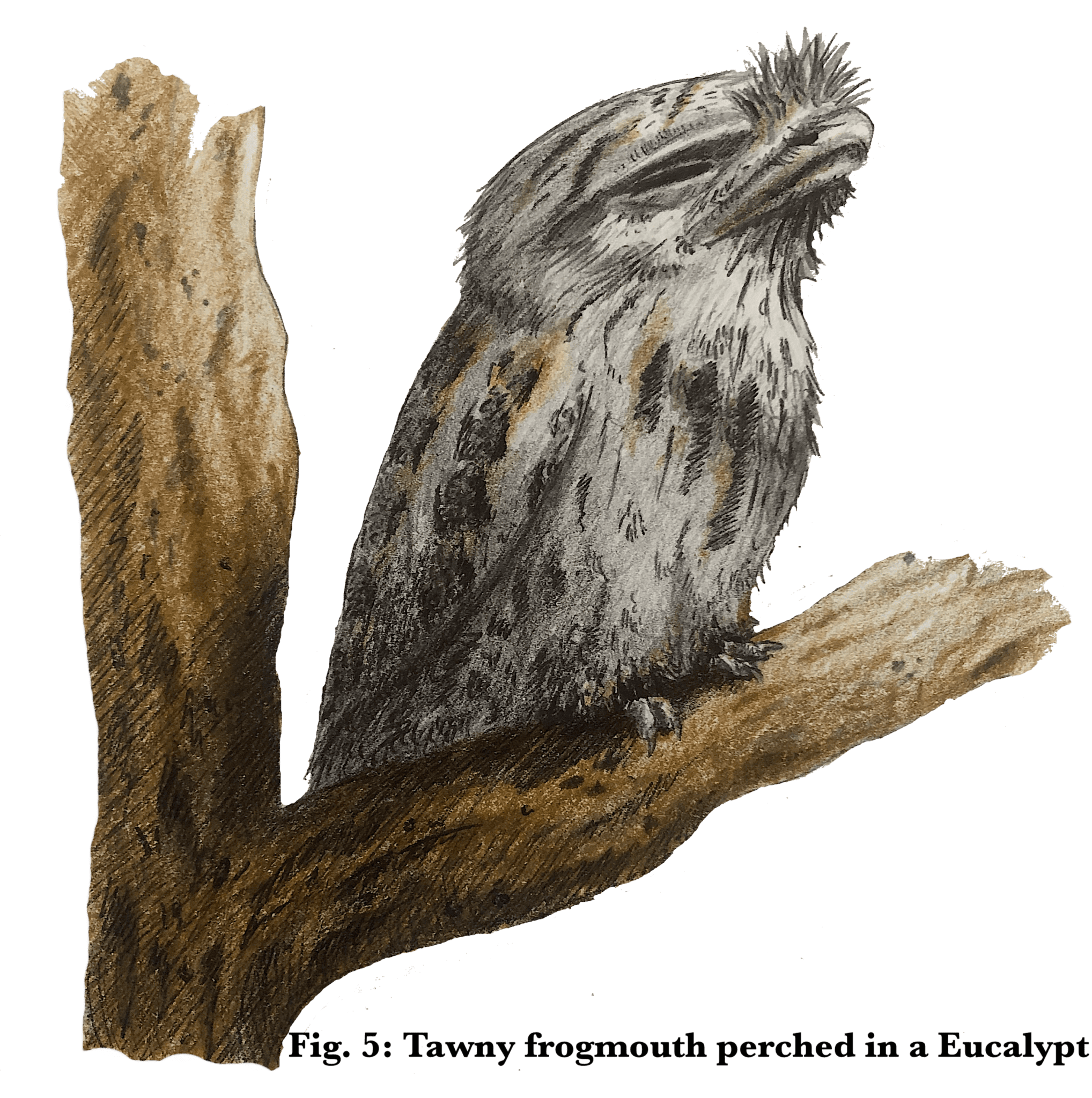

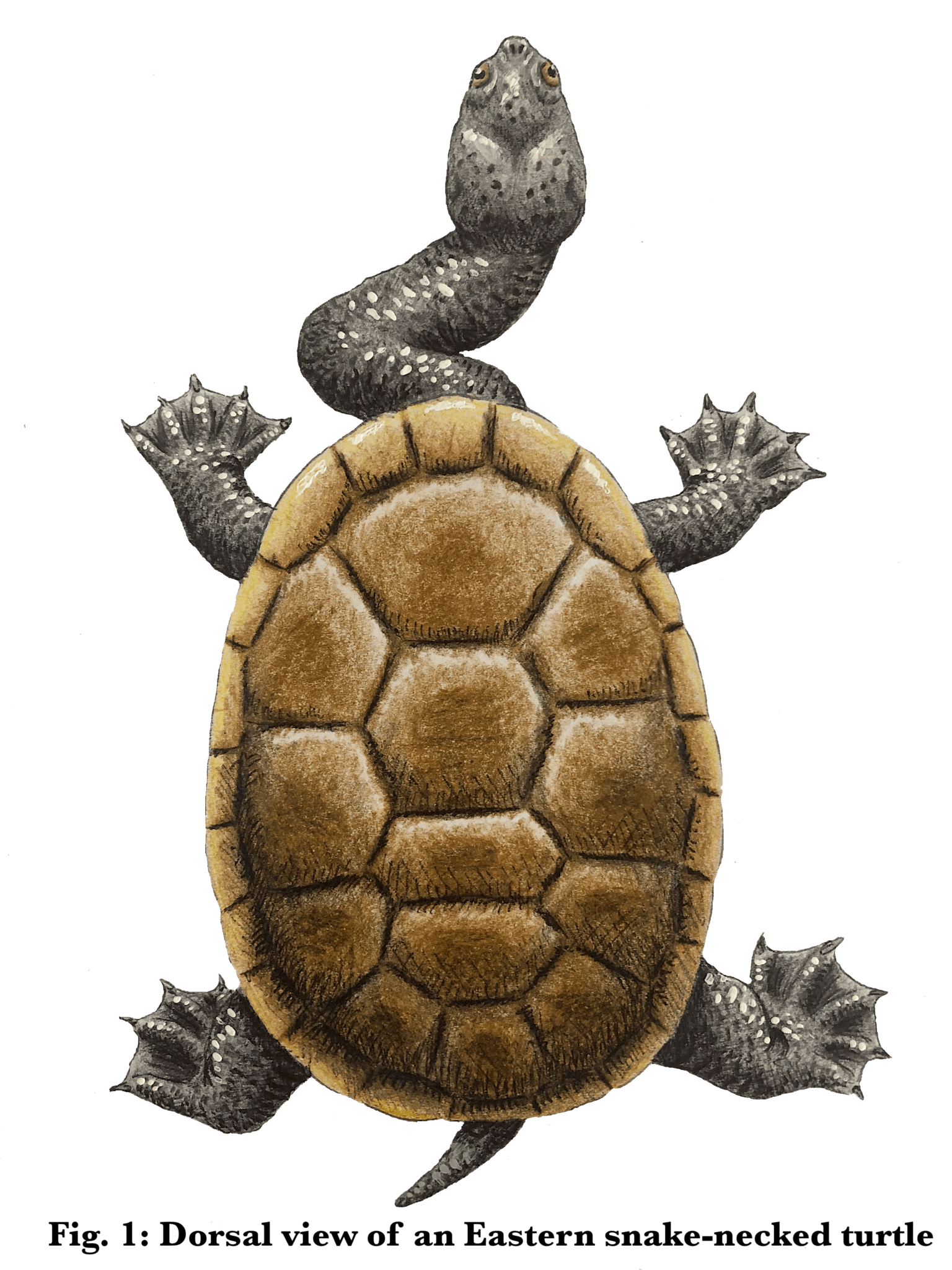

If I’m lucky, I’ll also glimpse a turtle. In this fetid urban swamp, there are not only native snake-necked turtles, but also a highly invasive Mexican red-eared slider. Morning is the best time to see them, when they come out of the water to sun-bathe and energise for the day. I sip my iced coffee and do the same.

Midday: black cockatoos, brush turkeys and bugs

In the full sun, out come the birds. One of my favourite things about Sydney is its parrots. Rainbow lorikeets and galahs are classics, but my heart belongs to the black cockatoo. These problem-solving birds are masters of cracking seed pods, and from their perch over Parramatta Road, they drop the husks onto unsuspecting pedestrians.

What I find most remarkable about parrots is their close pair bonds, each couple with a unique and complex love language. Lorikeets, I’ve discovered, have specific calls for “hello there,” “come here,” and “go away!” I even managed to record and play these from my phone, summoning the most confused bird of all time. I’d love to do the same for the black cockatoos, but they flee before I get the chance.

However, in the Sydney birdwatching scene, the watercooler topic is the southward spread of brush turkeys. A wily enemy, they are advancing on fronts from Strathfield to Bondi, and our scouts have spotted a beachhead right on campus. Opinions are certainly mixed on this mighty beast — something about the wrinkled head and dangling throat sack brings out strong feelings. Personally, I find them delightful. Their mounds, splayed across many a walking track, are pillars of defiance against humankind, symbols of the supremacy of nature. As the leaves decompose, the male turkey uses his beak as a thermometer, and keeps the nest at a toasty 33-35 °C. Entirely unrelatedly, the ideal temperature for a sensory deprivation tank is apparently 34 °C. I’ll leave those dots unconnected.

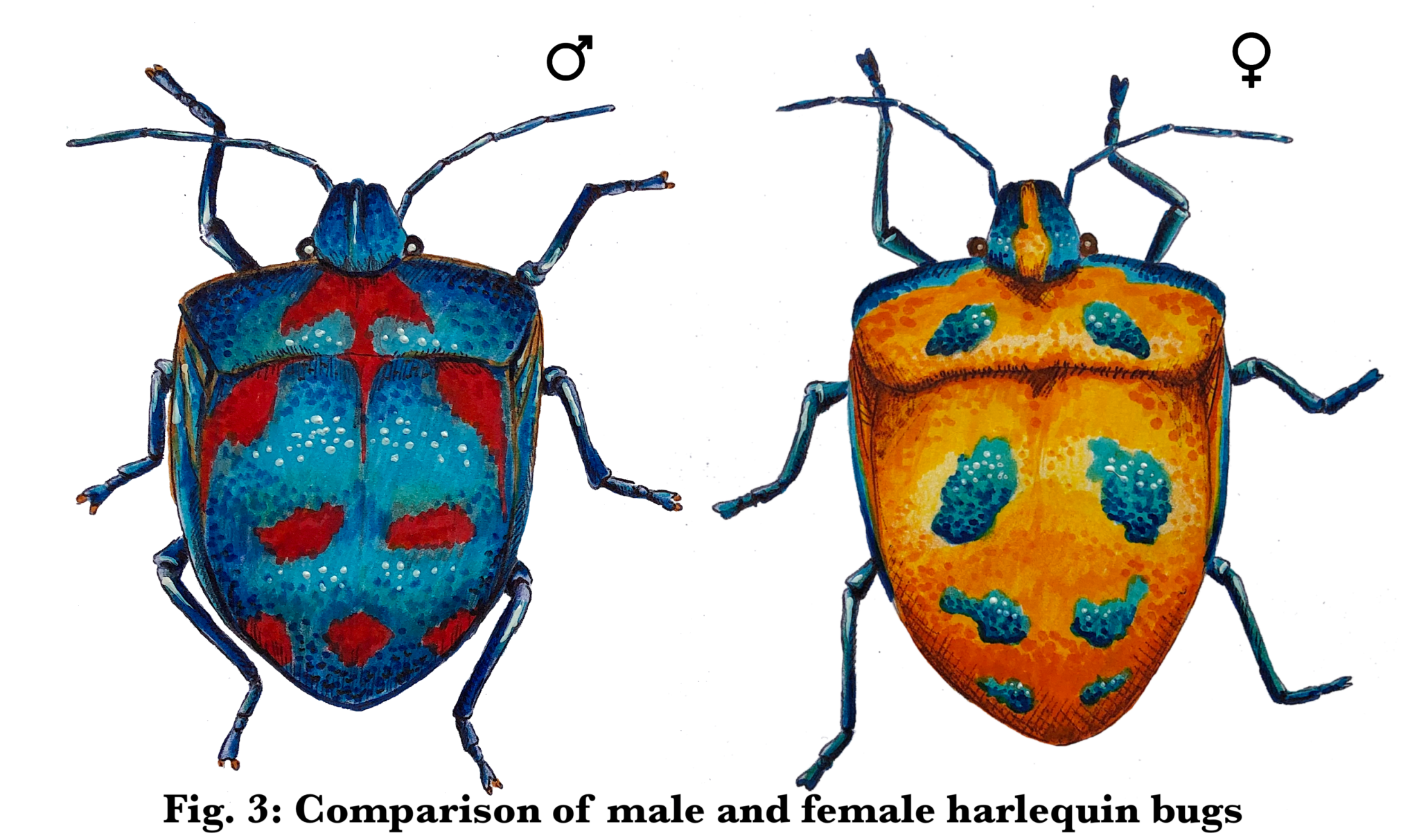

No field guide would be complete without mentioning our glorious insects. Camperdown is home to many species of bee: blue-banded, masked and European honey, to name a few. The cricket oval is actually a well-documented honey bee mating site. Every spring, without fail, males gather here to mate with young queens, everting their penis and killing themselves in a final, ecstatic burst. Everyone knows that, so let’s instead talk about harlequin bugs! About the size of a ten-cent coin, the males are a metallic blue, while females range from pure yellow to brilliant orange. Right now, it’s their breeding season, and if you check the branches of the Illawarra flame trees on Eastern Avenue, you’re sure to find a cluster, shining like expensive jewels.

Dusk: microbats

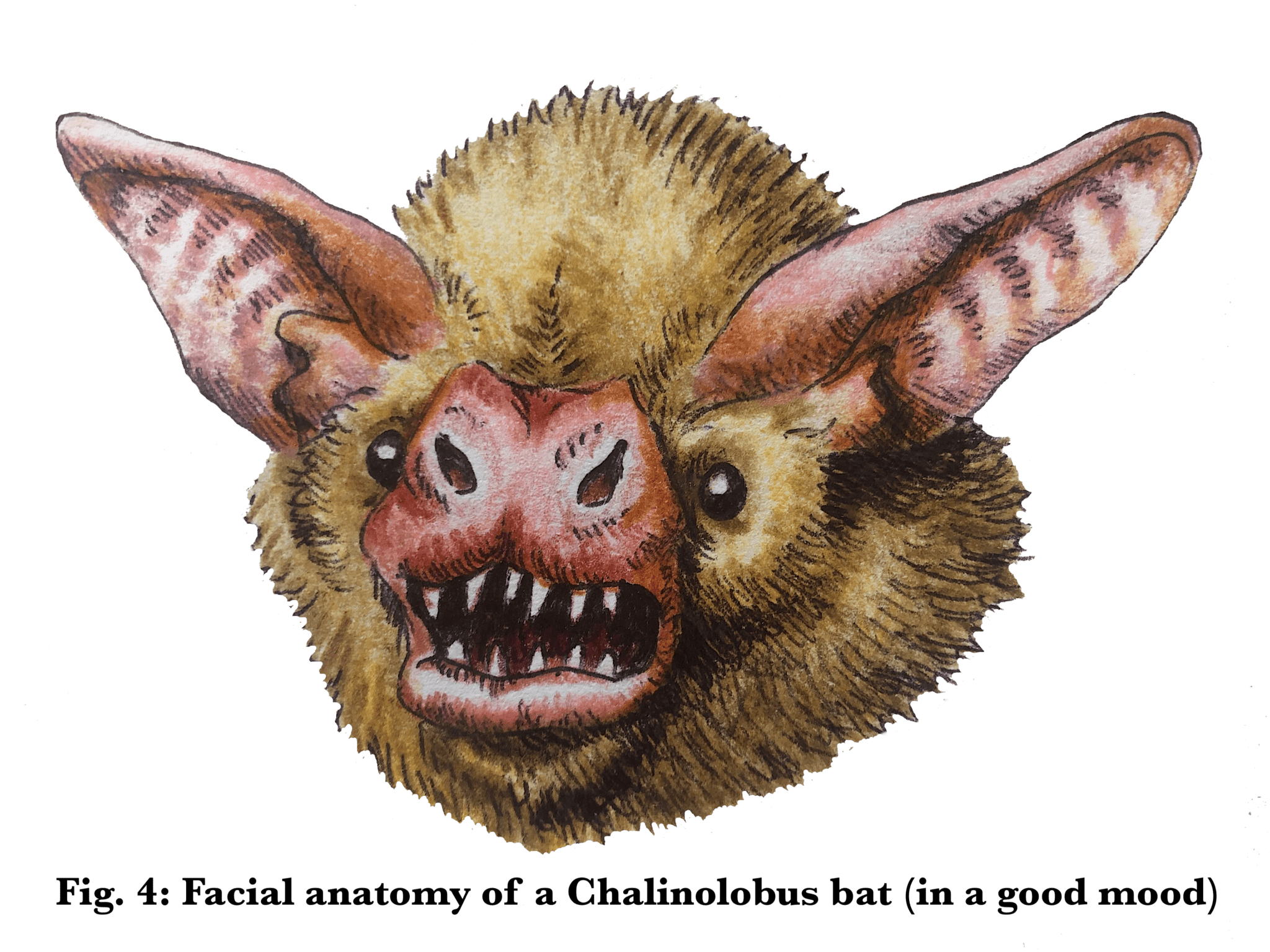

Ah, sunset, the most romantic time of day. Couples come to the Quad laws to watch the sky turn purple, or to snuggle by the fairy lights in Botany Garden. I often stand there, alone, to watch the microbats come out. These guys have earned their name: they would fit comfortably in the palm of your hand! On a good day, the sky around the Great Hall throngs with bats, each a zig-zagging black speck. With thrilling accuracy, they pluck insects out of mid-air and chase each other in tight spirals.

Night-time: frogs and frogmouths

Back in Victoria Park, the pond is now still. The ducks have nestled among the lilies to sleep, and the water is oily and black. Periodically, a microbat strikes the surface, managing a quick gulp before spiralling away. The pond is still, but it’s not silent. Throughout the warmer months, there is an omnipresent chorus of Peron’s tree frogs. From the bridge, with bullrush on both sides, their song is surround-sound, and you can usually find a soloist sitting on the handrails. For me, their cackle-like call is the true start of Summer, wherever it may land.

We finish with a favourite, the tawny frogmouth. A pedant will tell you that they’re not actually owls, but rather come from a related sub-family called nightjars. That pedant is me: they’re not actually owls, but rather come from a related sub-family called nightjars. If you ever see one take flight, you’ll be struck by the silence of its wings cutting through the air without the slightest rustle. On campus, you can spot them sitting in the crooks of gum trees as they wait for hapless frogs and rats to cross their path. Even if you haven’t seen one, you may well have heard it! Their call is a very rhythmic “woop – woop – woop – woop,” a bass forever waiting to drop.

Inner Sydney is far from wild. And yet, all these creatures have managed to find a niche in the urban jungle. We owe them a great deal, because in doing so, they have transformed mere brick and concrete into something dynamic and alive.