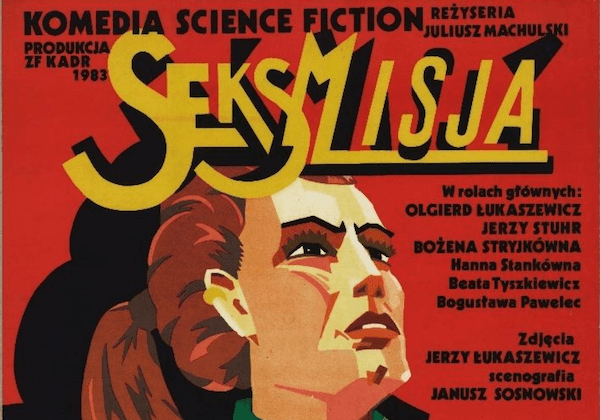

Sexmission is a 1984 Polish science fiction film directed by Juliusz Machulski, and starring Olgierd Łukaszewicz and Jerzy Stuhr. Panned by critics at the time, the film has since garnered a cult following for its satirisation of the Communist government. Some have come to recognise its more sexist and even transphobic elements over time, however. One must wonder, then, if these issues are endemic of the film itself, its genre, or perhaps its contextual milieu of contemporary Poland.

The film follows its two protagonists, Albert and Maks, two schlubby and arrogant working class men in the 20th century who abandon their families and are placed in hibernation. Intended to be thawed out after only three years, the men are instead woken up fifty years in the future, discovering the Earth has been ravaged by an apocalyptic WWIII and that the world is populated only by women. Seemingly utopian at first, this matriarchy soon reveals itself to be anything but the paradise they imagined, and it’s from this that they hatch a plan to escape.

From the opening moments of the film, Albert and Maks seem as though they are the villains of the piece. Abandoning their wives and children with little regard as to how they will live without them, before waking up in this future society dominated by the opposite gender, only to treat them with little respect, ogling them any chance they get —it is hard to believe that the framing of the film shifts to their perspective, and we are meant to side with them as the plot moves along. What seems like a satire of toxic masculinity at first, eventually becomes an endorsement of their behaviour. Women strip nude, with their naked flesh and genitals are on full display; delirious, unconscious and confused women are sexually assaulted by the two men and it is treated as either a moment of comedy or climactic achievement at the end of the film. The populace fawns over the protagonists, and the men are similarly thrown into wild sex driven frenzies at the mere sight of a boob.

In the climax, the head matriarch of the society is revealed to have been a man in disguise, only able to survive by dressing as the opposite gender. One could read this as the reason why the society was so dystopian in the first place, as it was run by a man and not a woman, but the film treats it more as a joke at his expense that he wore a dress. No attempt is made to try and probe deeper into questions surrounding their gender, and it seems that in this utopian society driven by women, there are no transgender men.

At the same time, the climactic reveal spreads harmful mistruths and myths about people using transgender identity as a ploy to invade women’s spaces. This misinformation is still running rampant today, with bathroom laws being a prolonged topic of debate. I could lie and say that transgender people were not considered during the filmmaking process. However, it was there, but only for the purpose of mockery and defacement.

Are these issues endemic to the film itself or a product of the genre it inhabits? As speculative fiction, Sci-Fi seems primed to tackle an evolving notion like gender. Many texts explore the liberation of the human form from the traditional limitations of the past, including the binaries of gender. Robert Heinlein’s All You Zombies is a 1950s short story blurring the lines between male and female as the protagonist transitions between genders through various time travel adventures, eventually giving birth to themself and ensuring the creation of their own life.

Feminist Sci-Fi has been especially popular of late, with television shows such as The Handmaid’s Tale, based on Margaret Atwood’s book of the same name, presenting a dystopian future ruled by an authoritarian patriarchy where women are subordinate and their bodies are merely vessels for birth. Many Sci-Fi texts, however, have not been so concerned with these issues. The image of the birthing machine, or the artificially created human — a recurring motif in Sci-Fi from Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, to Andrew Niccol’s Gattaca, and even Sexmission — is always presented as a sign of the dystopian, as if society has moved away from a more natural way of producing life. But if the genre is about the liberation of humanity, why is this not afforded to women? Astronaut Dave Bowman can evolve into a giant space baby at the end of 2001: A Space Odyssey, and Iron Man can survive explosive blasts in his metallic suit, but god forbid a woman is relieved of the stress, pain and anxiety of childbirth.

The issues and questions around childbirth are especially prescient for contemporary abortion laws in Poland. Right now, the government’s stranglehold on abortion laws is being increasingly strained, with the Constitutional Tribunal in 2020 labelling it ‘unconstitutional’ for women to abort a foetus showing signs of fetal defects. Female bodily autonomy is being policed to greater and greater extremes, and with protests by activists being met with brutal, state sanctioned violence, it is an inexorably hostile time to be a woman in modern day Poland.

The state of LGBTQIA+ rights is no better, with Poland, according to ILGA-Europe’s 2020 report, ranking as the worst country in the European Union. This is mostly due to the inseparable relationship between the Church and the State. For a transgender person, attempting to get gender reassignment surgery is made nearly impossible by an obstructive bureaucracy and hostile regulations. A proposal to make the process of transitioning easier was, unfortunately, vetoed by President Andrzej Duda.

As it stands, it is difficult to determine the toxicity that drives Sexmission, whether it be the sexist tropes that have dominated the Sci-Fi genre since its inception or Poland’s strict, dogmatic rule over sex and gender. This issue, however, runs deeper than one mere genre or country. There is a deep infection that runs through the veins of the entire planet, a stronghold that is choking the life out of the world: the patriarchal umbrella we all live under. If Sexmission truly wanted to imagine a dystopia, it need only depict our current world as is.