So, I’m an uncle now. That’s fun. Aside from the sudden whooping cough injections I needed to take, nothing has surprised me thus far. The crying, the pooping — these were all to be expected. What I hadn’t counted on, however, was the influx of photographs on my timeline. From TikTok videos, Instagram stories and Facebook posts, to snapchat replies, video calls and group chat images, it seems there is no escaping this child. I am confronted by their visage every waking moment.

The proliferation of these images bring up a number of concerns. For one, the eerie nature in which this child, who, from the moment of birth, has now been logged into a global system of data and code. Who knows who’s watching from afar and has access to my sister’s child? From the very beginning of life, it is as though they are already being tracked in an international panopticon of surveillance technology.

Aside from that, the way in which this newborn is being confronted by the steely gaze of a camera lens is unsettling to say the least. I wonder what this would do to a developing mind, to imagine your parent as the barrel of a camera rather than a human being: an artificial oculus, instead of a natural one. And to the photographer, the distancing effect this creates.

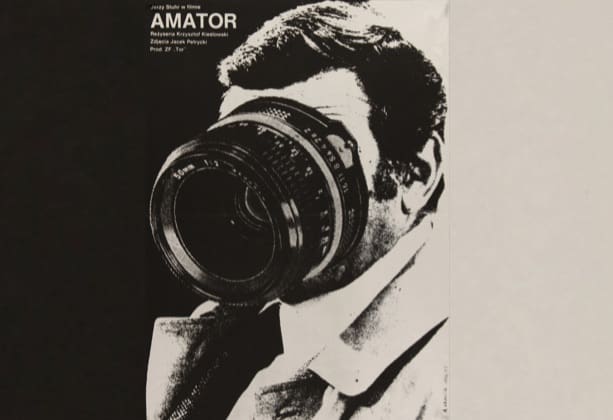

Krzysztof Kieślowski taps into similar concerns in his film Camera Buff, which follows the impulsive purchase of a film camera by a father to capture the early moments of his child’s life. As he begins to film everything he sees, an emotional barrier between him and his family starts to emerge. One scene sees him document his child sitting down but falling over, to which he continues to record without going over to help. His wife derides him through her rhetorical questioning: “If she fell off the balcony, would you film that too?” In an interview for the Criterion Channel, directors Josh and Benny Safdie suggest it acts as a warning to all filmmakers, asserting that film is “innately perverse” and “godplaying.” The horror of all this is captured in the Polish poster for the film, with the face of the protagonist morphing into that of a camera lens, an ersatz eye replacing an organic one.

This begs the question, why record these moments at all? What compels my sister to take photos of her newborn child? I sat down with her and my brother-in-law to gather deeper insight into their thoughts. For my sister, Hannah, she infers that “taking photos is a means through which to make physical my love for him and the affection I have for him through my own eyes, to then pass onto others.” For her husband, Joe, he spoke of how his desire to take photos of people he loves, such as his child, is driven by a need “to capture that moment in time, particularly because time is so fleeting – it allows you to look back on a moment and remember it for what it was.”

These responses point toward a larger notion that extends to all of us: the inherent reason we take photos of things and people we love. Since photography’s inception, people have carried photographs with them, whether it be in their lockets, wallets, or pocket watches, taking them wherever they go and refusing to part with them. A certain religiosity is given to photos, especially photo albums, which, when interviewing people who have just escaped their burning homes, often say it’s one of the first things they grab. Despite the prevalence of mobile phones, this still holds true, as the wallpaper of someone we love accompanied by a digital clock acts as a modern day pocket watch, and the camera rolls as a contemporary photo album.

It is the ephemerality of the image, something about it that we feel compelled to seize, capture and hold on to forever. In The Art of Travel, Alain De Botton discusses how when encountering the natural wonders of the world, we feel an urge to take hold of this moment and freeze its temporality through the process of photography.

For me, I take photos of my girlfriend, of the sunset, of friends and family in my life because I don’t want to lose them. I want to hold on to these people and things for as long as I can, because they may not be around forever. I am reminded of a scene in Kieślowski’s Camera Buff, a beautiful moment in which a man’s mother dies, and he replays the only footage of her ever captured on film. With tears in his eyes and in a darkened room, the two second silent footage plays before spooling out of its reel, and he says quietly, “she’s there forever now.”