I have a little shoebox that I keep under my bed. Once, it was baby pink, but now it is frayed at the edges and the cover has turned parchment yellow. I bought it when I was eleven, and in it, I put the very first love letter I received – a torn piece of notebook paper that said, “I like you even though you accidentally kicked me during P. E. Do you want to sit together in English?”

Over the years, I filled it with things I thought I wanted to keep forever: friendship bracelets from friends I knew I would lose with time, lily petals that have now turned a putrid brown, a ceramic ballerina from a music box that my brother broke as a toddler. These trinkets hold memories of people and places that don’t exist anymore. In the cutting of an artificial rose lies a summer afternoon spent spinning around a water fountain. Scraps of paper hold failed origami cranes and lost hopes of a constructed hinterland.

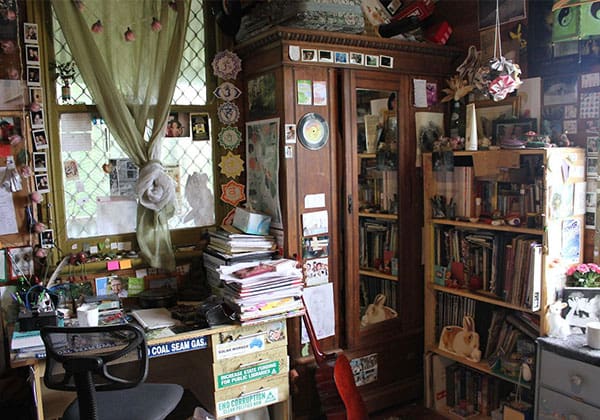

I don’t know when collecting items from my life stopped being a harmless hobby and morphed into an obsessive need to preserve the past. I worry about forgetting important moments and the people I’ve loved, however briefly. Still, I worry more about turning into someone who could discard such a memory to the clutches of oblivion. When I have things I can hold in my hand, magnetic bookmarks and heart-shaped pendants and fig-scented candles, I know that the people I have cherished are within reach. I recognise that it is foolish to assign love a tangible value when it is remarkably easy for things to wear, but this knowledge does nothing for the stacks of boxes I envisage in my future, all piled up in a closet I will shy away from opening.

When I was thirteen, my best friend gave me a plastic gem that she had 3D-printed and dyed purple. I kept it in my pencil case, a good luck charm of sorts, until we had a falling out. After that, it went in the box, and I bought a new container just to avoid looking at it. The gem disappeared multiple times over several months, but it somehow always found its way back to me. I started carrying it around in my hand when I began University; I would sit on the Quadrangle Lawns and watch the sunlight refract through it. I found myself wanting to lose it, needing to let go of everything it represented.

Now, as I sit on my bed with the contents of multiple memory boxes upended on my duvet, I find myself being unable to identify some of the items. I am not sure why I have a pink safety pin or periwinkle beads. The very purpose of starting this activity is lost to me, the act of collecting becoming more habitual than meaningful.

All my little trinkets reveal more about my personality than anyone else they might have belonged to. In my hoard of treasures, I see a thousand versions of myself. And with every new addition, I find myself thinking the same thing: someone, please, remember this. Remember I was here. And that I was loved.

Holding onto things from the past feels much like reaching across time for something unattainable. Giving old clothes away is always hard because I don’t want to lose that dress I wore at the party of someone who isn’t alive anymore, or the shoes that supported my weary feet as I made the uphill climb endless times on my last ever school camp.

A lot of this may simply be me confessing to being a hoarder, but love is stored in all the things that I cannot bring myself to throw away. Some of the memories, if not most, are lost to me but it is easier to hold something and know that it mattered enough to preserve than stand with empty hands and nothing to show for my life.

Because, really, what can one say for other people after they’re gone? Will having boxes full of miscellaneous items really satisfy me in the long run, whatever that might look like?

I have often been told that utility should be the primary function of an object, though I have never met someone who subscribes to that belief religiously. Sometimes, people just have things, lots and lots of things, and they needn’t do anything more than serve as a reminder of an old friend, or a day well spent.

I will happily clutch onto my purposeless possessions, satisfied with the knowledge that another version of me once did the same.