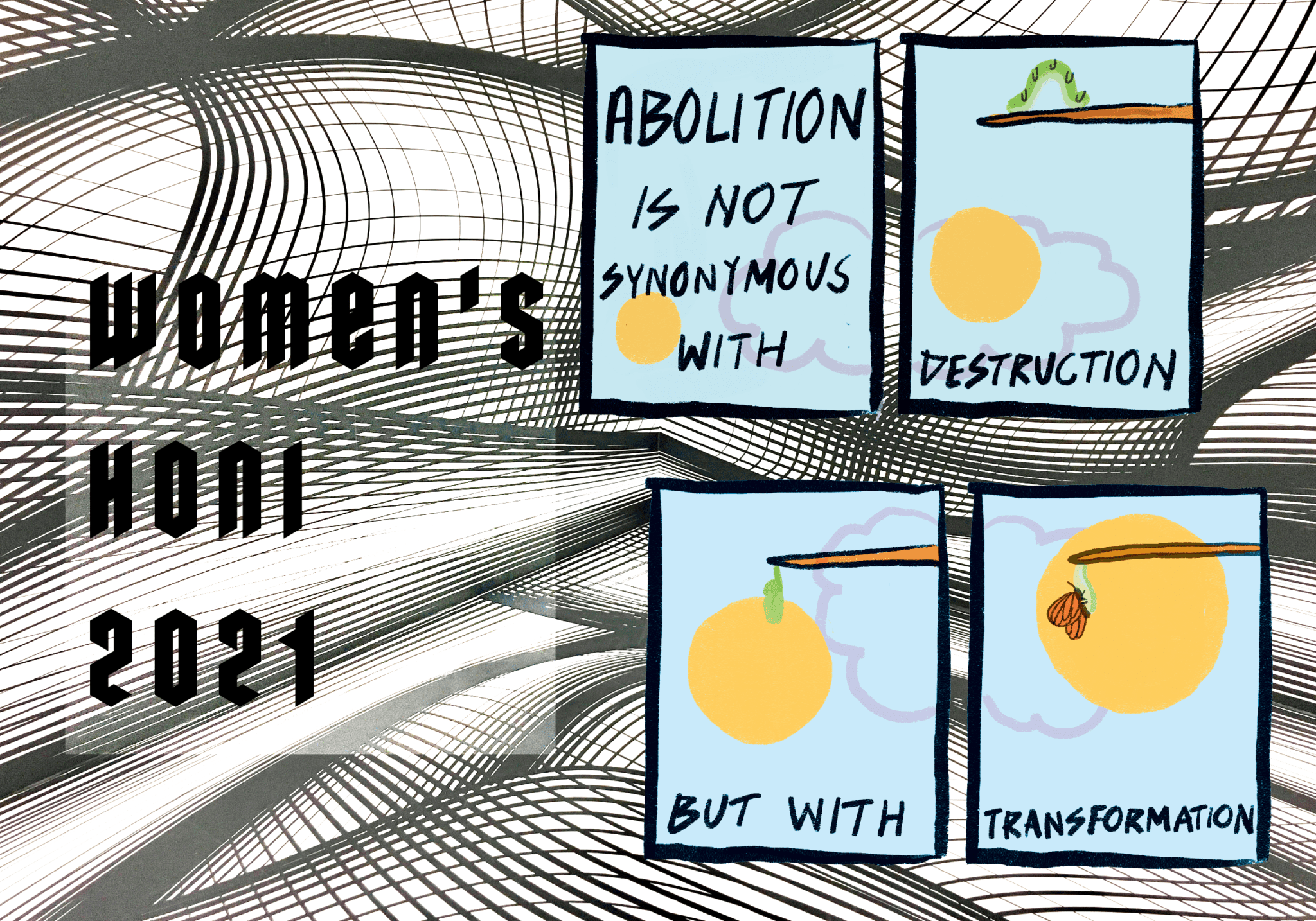

I would like to preface this article with an acknowledgement that the concepts contained within this text are the result of a continued accumulation of knowledge over decades, with key contributors being predominantly Black women and others at the coalface of carceral violence. Abolition is a process of change and transformation, and can not be attributed to one person nor claim to be a ‘finished’ concept.

I could not possibly hope to fully explain abolition within this short article, so I have listed a number of key abolitionist texts at the end which I recommend as further reading.

The rise of the Black Lives Matter movement on a global scale in 2020 brought with it increasingly popular calls to ‘defund the police’ and ‘abolish the prison industrial complex’. Abolitionists, activists and hyper-policed communities around the world welcomed this, as the broader public openly discussed the ideas of abolition for the first time. Within Australia, Indigenous activists organised some of the largest demonstrations against police brutality in decades, highlighting that over 470 Indigenous people have died in custody since 1991. However, as is natural with social change, increased discussion of new topics brings about misleading information and active opposition. This article is an attempt to counter this by providing an explanation of the core ideas of abolition.

What is abolition?

The basic premise of abolition is that the use of carceral control and surveillance as a way to address deeply ingrained and often systemic social issues is not only inadequate, but exacerbates violence and harm. The abolitionist argument is that resources must instead be re-allocated towards dismantling systemic sources of violence and harm within society; poverty, racism, patriarchy, ableism, and all other forms of structural inequality. Abolition is not an argument for ignoring social unrest and violence. It is an argument for addressing the root causes of these issues. Rather than punishing people for systemic processes which impact their environmental circumstances, we need to radically transform the negative environmental circumstances which lead to social unrest and harm. Abolition means not only abolishing the existence of prisons and police, but developing processes of transformative justice, and creating the environmental conditions to allow communities to thrive.

The systemic issues acknowledged by abolition are rooted within the violent processes of colonialism, capitalism and imperialism, and thus prison abolition is inherently anti-colonial, anti-capitalist and anti-imperial. This means acknowledging how states control and police marginalised groups while neglecting to provide adequate resources to sustain healthy and safe environments. It also means acknowledging the power imbalances which see white Western cultural hegemony undermine the importance and value of non-Western ways of understanding health, justice and community.

Abolitionist thinking also acknowledges that those who commit what is seen as crime — violent, non-violent and everything in between — are not experiencing violence or injustice for the first time when they commit these crimes. Experiences of trauma, poverty, and exploitation are not simply fixed by locking up those who react negatively within their environmental circumstances. The underlying causes of violence and harm do not disappear once someone has been relocated into a prison cell. Nor does placing someone in prison undo what has happened, or necessarily stop it from happening again. Considering that 46% of Australian prisoners return to prison within two years of being released, it is clear that the current system does not adequately end cycles of violence and harm. What is needed instead is a response which addresses the underlying causes of crime and social unrest. Abolition calls for a transition away from a societal preference for punishment before prevention and transformative justice.

Why not reform?

Alongside calls for the abolition of prisons and police have been calls for carceral reform, for diversity training, improved surveillance of police actions and tighter restrictions on the extent of allowable force. If the goal was to fix a broken system then these might be good ideas, because reform is used when something is broken and can be incrementally fixed in order to work ‘properly’. But the carceral system is not a ‘broken’ system, it is working in the exact way it was set up to work; to control and police the citizens of a state to act in the interests of the state. Under capitalism, and especially within colonial states, this means the hyper-policing of Bla(c)k, brown, disabled and poor bodies to conform to a system which exploits them. Even if police themselves were completely unbiased and removed from omnipresent racist, ableist and patriarchal attitudes (which is not possible), they would still exist as an arm of the state which works to uphold laws to protect economic interests and the ever-increasing profits of capitalists.

The carceral system is intrinsically tied to the processes of capitalism and colonialism, with the first police forces invented to serve the interests of slave owners and capitalist bosses. Prisons today still work in the same way, with the existence of highly profitable private prisons showing just how linked capitalism is with carceral control. Police, prisons and other forms of carceral control are tools of the state, and work for those who run it; capitalists who rely on exploitation, such as prison labour, to gain profits. It is for this reason that we can not simply ‘reform’ the police force, the state will always work to uphold market interests, and the threat of carceral control is necessary for continued capitalist exploitation.

No amount of diversity training will stop police officers arresting Indigenous activists fighting against mining companies, because the police force will always serve the interests of the capitalist state, and the state will always serve the interests of the market. No amount of surveillance of the actions of police would stop bosses legally using the state to crush union strikes for conditions and pay. The police, and subsequently prisons, do not and will never work for anyone but the state and the capitalists who run it, and no amount of reform can change this.

But what about justice?

The absence of prisons is not the absence of accountability when harm occurs. It is necessary that responses to harm do not continue cycles of violence by perpetrating further harm. The reality of the carceral system is that it does not reduce harm; rather, prisons are sites of state-enacted violence, used in place of providing real care to those who need it. Those who enter the carceral system and are lucky enough to leave bring with them higher levels of lifelong poverty, increased levels of mental illness and suicidality, and poor physical health. Prisons are not places of safety, support and rehabilitation.

Those with experiences of addiction will not find the rehabilitation they need within a prison cell. Someone with a history of childhood trauma will not find the mental health support they need within a prison cell. Instead of providing the care needed by people struggling, prisons punish in the name of deterrence away from what is defined as crime, but deterrence through fear does not end the causes of social unrest.

Prisons are seen as the ‘answer’ to issues faced by systematically marginalised groups, while medical care, therapy and access to support is the answer for those with higher levels of privilege. The difference between receiving adequate care and being placed into a prison cell is directly related to your class and racial identity.

But what about violent crime?

One of the most common rebuttals to the ideas of abolition is the need to address domestic violence, sexual assault and violent crime. This is a fair point, there is absolutely a need to address the existence of these acts within society. However, how does prison stop these acts of violence from being committed? Does the existence of prisons undermine the existence of the patriarchy? Does the threat of jail time meaningfully impact the actions of perpetrators of domestic violence? When conviction rates are so low and victims are rarely able to achieve justice within courts, should we not be looking towards addressing these crimes at their root cause? Similarly, does the threat of jail time stop someone who is starving from jumping someone to steal their wallet? Clearly these acts are still committed, despite the existence of prisons. The only way to stop these actions is to end the circumstances which lead to them: to end poverty, destroy patriarchal gender dynamics and ultimately create the circumstances where these acts do not occur. It is therefore imperative that resources are allocated into initiatives which seek to address, and eventually end the existence of these violent acts, and that money is not simply spent on increasing prison capacities for when crimes are eventually committed.

Practical steps forward

While the goals of abolition: to dismantle prisons, abolish police and radically transform society in the process may seem impossibly large, this does not mean that small yet tangible steps cannot be taken to get there. Abolitionists work not only to undermine the carceral system, but also all facets of systemic racism, patriarchy, and capitalist exploitation. Abolitionists seek not only to destroy the systems, institutions, and laws which cause harm, but also to build alternatives which empower and transform individuals and communities. This means taking actions such as fighting for an increase in welfare support, secure housing, access to education, and a prioritisation of culturally specific and community run services.

Abolition is a process, and is something that we must constantly work to further and improve. It is something that we can work towards every day, through the way we interact with others, engage within our own communities and involve ourselves in social movements. In the process of achieving abolitionist goals we need to build new ways of engaging with the world, on every level of social interaction. The social relationships which exist to shape the societies we live in are enacted by people, and thus can be changed by people. The way things are now is not simply the natural state of things, and it has not always been this way. In order to achieve the just and fair world abolition calls for we need to restructure society in a revolutionary way, and nothing less than the destruction of capitalism, patriarchy and systemic racism will get us there.

Resources

Angela Davis – Are Prisons Obsolete? – YouTube; “Angela Davis: Abolishing police is not just about dismantling”

Ruth Wilson Gilmore and James Kilgore – The Case for Abolition (online article)

Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha and Ejeris Dixon – Beyond Survival: Strategies and Stories from the Transformative Justice Movement

Mariame Kaba – We Do This ’til We Free Us