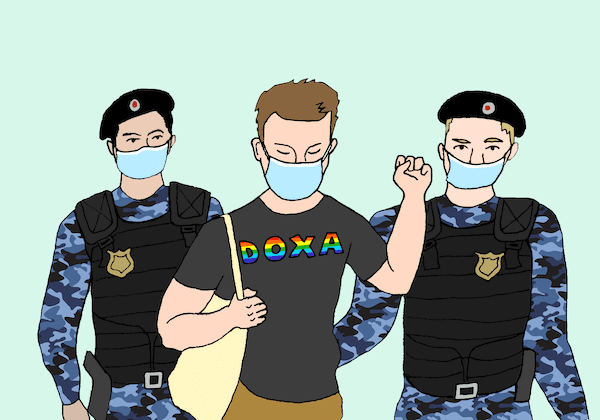

At dawn on April 14, Russian police raided the office of Doxa — a Moscow-based student newspaper — and six flats belonging to editors and their parents. They rifled through cupboards, clothes, took apart printers, confiscated phones and laptops, and — absurdly — combed through 10kg of nuts. At the home of one editor, a translator, they asked: “why does he have so many books? For what reason?” Four editors: Armen Aramyon, Natalia Tyshkevich, Vladimir Metelkin, and Alla Gutnikova, were arrested, charged with ‘involvement of minors in hazardous activities’ and placed under strict 24 hour house arrest.

Emerging at the height of Putinism in 2017 at Moscow’s Higher School of Economics as a small student newspaper highlighting issues of precarity, harassment and inequality within universities, Doxa has become an instructive case for the decline of student rights, academic freedom and independent media in an authoritarian Russia. As the case against the Doxa four draws out, Honi Soit spoke to two editors, Victor Ershov and Ekaterina Martynova.

Erosion of staff and student rights

In the brief period since Doxa’s founding, academic freedom and autonomy has suffered a precipitous decline. Centralised government control of universities, weaponisation of vague legal instruments, weakening of unions and activists groups, and underfunding have combined to create a culture of overt and implicit censorship. According to Kataryzna Kaczmarkska, “scholars work in a climate of uncertainty and share the perception that they can be reprimanded at any time” while students face disciplinary action for expressing anti-government views, and are restricted in the areas which they may study and research.

In Russian universities, Rectors (the equivalent of Vice-Chancellors) are directly appointed by the government, and often have close connections with, or membership of, the ruling United Russia party. A recent Doxa investigation found that 74% of university Rectors had government connections. Foreign interference laws have been weaponised to close down independent funding bodies, and recent amendments to education laws require that universities inculcate students with “spiritual and moral values, including a sense of patriotism.” Meanwhile, academics and students have been sacked, disciplined or expelled for ‘unpatriotic’ research or views, and student organisations have faced harassment from university management and the law.

One summer at HSE

Events at HSE, once home to Doxa, demonstrate this decline.

Once considered to be Russia’s most liberal university, as recently as 2017 HSE offered legal assistance to students detained in protests. Its senior management told police that they could not “eat our children.” However, since the summer of 2019, which saw a wave of anti-government protests over the refusal to register independent candidates in the Moscow Duma elections and the imprisonment of Alexei Navalny, HSE has taken a decidedly authoritarian turn.

Political science student and prominent opposition blogger Yegor Zhukov was a candidate in the Moscow Duma election, as was Valeria Kasamara, the Vice-Rector of HSE, who ran with the support of United Russia. Zhukov’s campaign was cut short and he was arrested and charged with ‘extremism.’ As staff and students rallied behind Zhukov, HSE administration began to crack down on student activism and academic expression. Ekaterina Martynova, an editor at Doxa, told Honi that students were “threatened with administrative sanctions” for attending protests, and that “many unis said to students that if you go to protests you’ll be out of university.” Doxa, which had criticised Kasamara’s candidacy and ran crowdfunding campaigns for detained students, was deregistered as a student organisation for ‘damaging the reputation’ of the university. Martynova says that “it was obvious that it was a political decision” and that they were told that Doxa was “too independent to be a student organisation.”

Over that same summer, HSE academics found themselves gagged and harangued, triggering a number of resignations.

Political scientist Elena Sirotkina resigned her post after, as Kaczmarkska says, “university management pressured her to withdraw from a research project on activists and supporters of Alexei Navalny.” Political Science professor Alexandr Kynev resigned after the Department of Political Science was merged with the Department of Public Administration, ostensibly to prepare students for ‘real life.’ Kynev has said that “they are trying to clear a place for the ‘right’ friends and take control of an important segment of the university.” Doxa reported that the university lost 28 academics for “political reasons” in the summer of 2020 alone.

A number of academics removed by HSE in 2020 were involved in setting up the ‘Free University,’ which seeks to “rebuild the university from scratch…freeing teachers from any administrative dictate. If the university can no longer be free, then a new free university is needed.”

“We cannot be expelled from the university, because the university is us.”

The clear signals sent by university administrations have discouraged current students from pursuing their academic ambitions. Victor Ershov, who studied History and Art History at St. Petersburg University, left because he was unable to freely research “about inequality, homophobia…our modern problems.” Ekaterina Martynova says that “there are less opportunities for young researchers to conduct their own papers and projects because there is no funding except from one or two government organisations.” She plans to leave the country because “I cannot perform my own research because I will not find the money and I will not find work at my home institution [HSE].”

Later in 2020, Zhukov was expelled from HSE as management introduced regulations in pursuit of a “university beyond politics,” effectively prohibiting student activism and placing heavy restraints on staff. Under the new regulations, staff and students are prohibited from “making political statements not only on behalf of the entire university, but also on behalf of any group of staff or students at HSE.” Staff are not allowed to “go beyond the bounds of their expertise or analytical position” when speaking or writing in public. The most oppressive regulation reads: “in case of participation in political activity or some other activity that is socially divisive, the student or employee will be required to take measures to end their affiliation with the university.” All student publications were banned, and Martynova says that “organisations doing political debates and holding meetings to discuss current issues also faced these restrictions.”

The only student platform recognised by HSE is the Student Council, which is required by law at all universities. However, Ershov says that these councils “are a token parliament” used as “a career springboard for administrators and politicians…Student Council is about as independent as the Russian Duma.”

At a forum to protest against the new regulations, Vice-Rector Valeria Kasamara — the United Russia candidate — told students “If you choose a state university under the government of Russia, then you must recognise that there is a founder who sets the university’s goals and objectives.” That founder, Yaroslav Kuzminov, resigned in July. Once hailed for promoting academic freedom at his university, the Moscow Times lamented that “it was this that tore apart his power, and he was forced into compromises and obedience.”

Media targeted

Despite losing their registration, Doxa ploughed on. Whereas once their focus was issues of “precarity, harassment and inequality in universities,” as a result of their deregistration, they have, as Martynova puts it “suddenly become real journalists.”

In April, Doxa found themselves the latest target of a crackdown on independent media. In January, they published a video in which four editors encouraged students to express themselves politically and, according to their lawyer, “explained the illegality of threats from the leadership of universities about expulsion for participating in protests.” Three days later, Roskomnadzor, the federal communications watchdog, ordered them to take the video down because it “aimed to induce or involve minors in committing illegal activities” (ie. protesting). Doxa complied and Martynova says the editors took little notice of the order: “that’s life in Russian media.”

However, over the subsequent months, police began to “watch our four colleagues around the city.”

In April, editors’ homes and the Doxa office were raided by police, and the four editors who appeared in the video were arrested on charges of “involvement of minors in the commission of acts that pose a danger to the minor’s life,” which carry a maximum sentence of three years imprisonment.

Since April, the four editors have been held under strict house arrest as their case drags on. Originally prohibited from leaving their homes entirely, they have since been allowed outside for two hours each day. They are prohibited from communicating with each other, and from using the internet.

Ershov and Martynova believe the proceedings are being deliberately drawn out. “We expected a trial in July, and then in August. I think they will prolong as long as they want, maybe until after the Duma elections [in September]. They are afraid that Doxa will publish something calling people to protest, but it’s just insane,” says Martynova. Ershov speculates that “perhaps the government just want to leave our colleagues as hostages to intimidate us and to prevent us from covering mass protests that can be expected after the next elections.”

With the United Russia party suffering record low approval ratings heading into September’s national Duma elections, and with increased attention on the treatment of opposition groups, media suppression has increased markedly. Independent media organisations throughout Russia have faced deregistration, harassment and legal sanctions, with ambiguous ‘foreign agent’ legislation used to arbitrarily silence independent journalists and publications. Since April, leading independent news organisations such as Dozhd, iStories, and Meduza have been all been declared ‘foreign agents’ while Proekt, which Doxa has collaborated with, was declared an ‘undesirable organisation’ in July.

Ershov says that “every three to five days the Russian government is shutting down another media organisation.” While Doxa’s structure somewhat insulates it from interference: “we don’t have a hierarchy, so it’s much more difficult for the government to stop our work as the police just don’t know who’s doing what,” the spate of closures, arrests and imprisonments still has an effect.

The paper is kept afloat by donations, and editors have been working 60-70 hour weeks campaigning for their colleagues, writing articles, and producing the publication, while facing the continual threat of arrest. Martynova left the country for her safety, while Ershov describes the pressures of independent journalism in Russia: “We live in a different reality. We live in a country where your house may be raided by police at any time. It’s so, so dangerous. We just want life as usual.”

.