Like a boulder (or microscopic, yet angry virus) dropped into a glass-still pond, the effects of COVID-19, both positive and negative, will stay with the Australian health system for a long time. We were reminded of this when, just as life began to resemble normality, the Delta strain outbreak began to take root in Sydney.

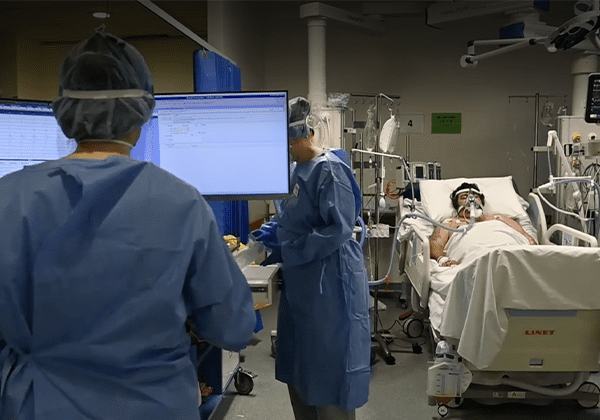

While the daily COVID-19 cases were presented to the ordinary person as numbers on a screen every day at 11 o’clock, the reality in hospitals was far worse: overloaded ICUs, overworked healthcare professionals and patients whose procedures are put on pause in order to handle the hospital system’s rapid loading with COVID-19 patients.

Overloaded Intensive Care Units

The hospitals currently under the most strain in lockdown are the South-Western tertiary centres, namely, Westmead Hospital, Liverpool Hospital and Nepean Hospital. The ICU in particular is critically under-resourced.

To better understand what it all looks like on the inside, I spoke to Dr Edgardo Solis, head of the surgical association and a doctor on the general surgical team at Westmead. He had just started his elective ICU rotation at the beginning of the recent Delta outbreak and, with the preface that he “can only speak from Westmead’s experience,” begins by telling me that “half the hospital is basically a COVID hospital.”

In Dr Solis’ experience, the staff and hospital system had to “restructure itself” to “minimise foot traffic [and] minimise exposure risk…[in order to] mobilise fewer resources to provide adequate care to this increased demand.”

“I don’t think we expected things to change so quickly in the general ICU, so when I first started [rotation] on ICU a few weeks ago, we knew we were going to get hit hard but we didn’t know the speed of COVID was going to be so intense,” Dr Solis told me. “This is a disease, [and] I have to admit I have a limited exposure to respiratory illnesses [compared to respiratory physicians], but the aggressiveness…these people can be incredibly ill…they’re walking a very tight rope between keeping themselves together and going into full respiratory failure.”

These incredibly unstable patients require more intensive monitoring and equipment to monitor, and Westmead’s general ICU unit has been converted to what is effectively a COVID-19 patient only ICU. Non-COVID-19 patients requiring the ICU have been displaced to a smaller sub-specialty ICU. Previously, there were 38 beds available to critically unwell patients, but now there are only 15 ICU beds for patients not infected by the virus.

Not to mention, if any of the COVID-19 patients on the general wards deteriorate, and they do — unpredictably and rapidly — they now need the support of an ICU that is already at full capacity. “In ICU, we’re under the pump 24/7,” said Dr Solis. “On a daily basis we’re being exposed to this. I think when people like the Health Minister say the hospitals are coping, it gives a false sense of what is actually happening. It really actually undermines the work that the people in the ICU are doing at the moment, not just in the ICU but in the hospital entirely. It really undermines the stress and the workload that we are all under at the moment.”

Under-resourced environment — no, it’s not just about masks

When we speak about resources, we tend to think of tangible things: masks, gowns, staff numbers. Intangible resources such as pandemic specific skills to manage the COVID-19 outbreak are also in high demand. Alice*, a junior medical officer working in a non-tertiary hospital chuckles lightly and states, “this was not what any of us had in mind at graduation — we weren’t trained for a pandemic.”

As hospitals deal with a desperate need for skilled staff, junior staff members must take up the mantle. Dr Solis describes the race that is on to upskill junior staff members in order to equip them with the crucial skills for managing unstable respiratory patients. In hospitals, one staff member is not equal to another, so whether a system is ‘well-staffed’ cannot be measured by the number of bodies working within it.

Despite working in extremely strenuous conditions, healthcare workers are without adequate mental and social support. They must handle (often futile) emergency resuscitations, perform intensive CPR on patients who deteriorate unexpectedly, then inform family members exactly why they will never see their father, mother, sibling or child again.

“If you’re like me and your family lives outside of your LGA, you haven’t seen your family since July, June, since this lockdown started, and you see these highly stressful things on a daily basis…this is to us a battlefield,” Dr Solis said. “But you have to keep going, the patients are still coming.”

Even when it’s over, it’s not over

As we all pine for the ‘end’ of the Delta outbreak so we can go back to buying overpriced coffee (rather than ordering it from Uber Eats) and frolicking in the sun, the healthcare system will not be so fortunate when that time comes.

Many patients with non-emergent surgeries have had their procedures postponed indefinitely. Dr Solis speaks about the backlog of surgical cases that must be done in a timely fashion post pandemic, meaning healthcare workers can expect nothing but more elbow grease.

Specialist accessibility has negatively affected chronic disease patients as well. Nick*, a cancer survivor, states that he was not able to see his cardiologist for over 3 weeks due to the pandemic. He has recently been hospitalised for a deterioration in his cardiac condition which required emergency intervention.

Non-urgent cancer patients who required further investigations prior to receiving a complete diagnosis may find themselves with a prognosis worse than what it might have been if the pandemic did not put our medical system on hold.

Tracy*, an administrative staff working at a Sydney Ophthalmology practice expects “pure chaos that’s going to come from the rescheduling [of medical procedures]”.

The silver lining

Of course, it’s never a bad idea to find the silver lining in what has otherwise been a harrowing pandemic. Dr Solis states that this fight against COVID-19, despite being a “warzone” for health professionals, has reminded everyone of “what is at the core of being a healthcare professional — it has always been about the patient”.

Administrative and communication systems have seen rapid improvements in their flexibility and accuracy as they adapt and rise to the challenge of high-volume rescheduling and follow up. People are kinder, words are softer, and an extra layer of empathy can be found in each exchange. Within the hospital system, the unification against a common microscopic enemy has fostered comradery and congeniality. Egos are put aside, the red tape is peeled away, and as Dr Solis summarises, “I don’t know how long it will last, but we definitely will have a much softer approach with each other after this.”

* Some names have been changed to protect the privacy of our interviewees at their request.