Frida Kahlo and Vincent Van Gogh are two of the world’s most well-known and beloved artists in the western art history canon, yet neither of them is often associated with the term ‘disabled’ in popular culture.

Whilst Kahlo is best known for her iconic eyebrows and traditional Mexican attire, many wouldn’t know that her signature long skirts were chosen partly to disguise a thinner and slightly shorter right leg due to childhood polio. Even her choice to become an artist was influenced by disability following a bus accident at 18. She had previously planned to attend medical school, but the resulting chronic pain and injuries from the accident led her to begin pursuing painting whilst she was bedridden recovering. In later life, Kahlo became a fulltime wheelchair user as well as a below knee amputee following complications from the decreased circulation in her right leg. She customised her prosthetic leg with a painted red boot.

(left) Frida Kahlo, ‘Self -Portrait with Portrait of Dr Farill’ – 1951 (right). Frida Kahlo’s customised prothetic leg.

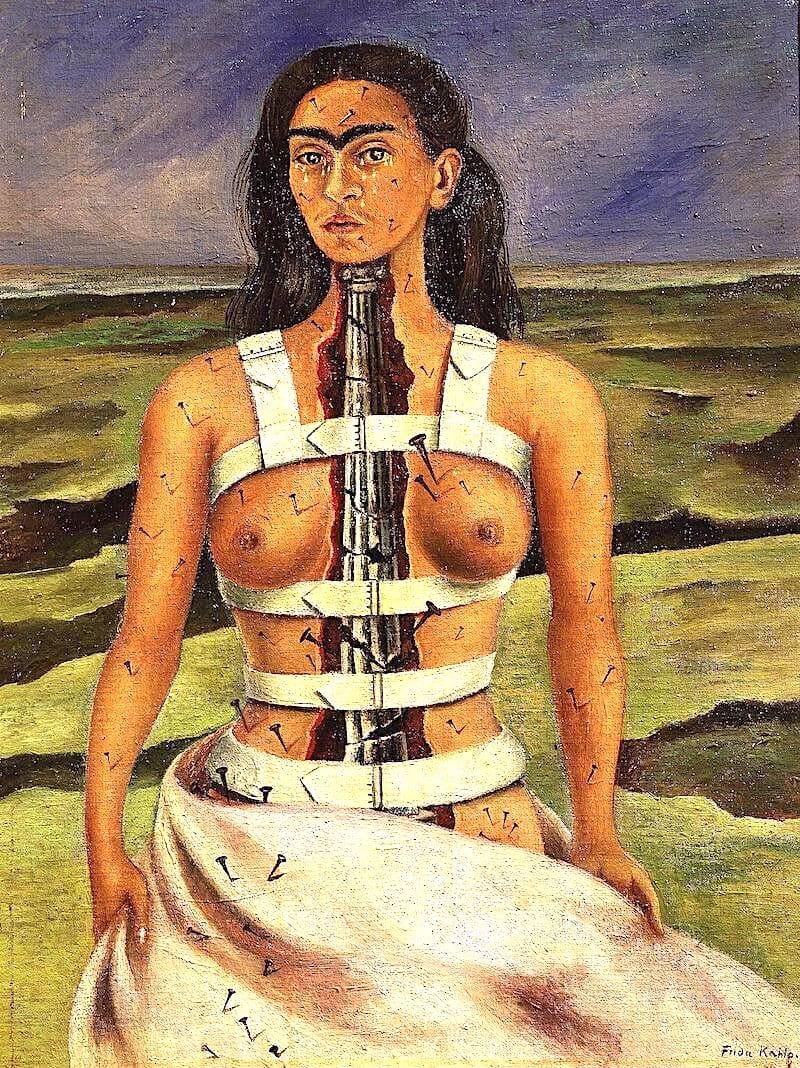

Through her self-portraits Kahlo explores her relationship to her disabled body. She once explained, “I paint myself because I am so often alone and because I am the subject I know best.” In The Broken Column (1944) for example Kahlo stares boldly at the viewer as a fractured Ionic column slices through her body, emblematic of her spine on which she had just had surgery. She stands amongst a cracked, arid landscape as her ruptured body is held together with a metal corset as nails pierce her flesh, a symbol of her chronic pain.

(above) Frida Kahlo, ‘The Broken Column’ – 1944

Van Gogh on the other hand is more commonly associated with his disabilities, although they are not often named as such. Instead, Van Gogh’s narrative is one of an ‘eccentric artist’ who cut off part of his left ear, his madness an essential ingredient in the creation of his artwork rather than a complex set of disabilities. What is often unknown is that Van Gogh’s most prolific period was when he was institutionalised and receiving treatment. During the time he spent in a mental hospital, Van Gogh made approximately 150 works including one of his most famous, The Starry Night (1889). It is also theorised that a medication the Van Gogh was prescribed to treat his seizures had the side effect of experiencing yellow more vividly. Hannah Gadsby makes this point in her widely acclaimed comedy show Nanette in response to criticism that taking medication would dampen her creativity, preventing the creation of great works such as Van Gogh’s Sunflowers (1888-89). We have the sunflowers not because of Van Gogh’s suffering but because he received treatment. His suffering was not in fact a requirement for him to make great art.

(above) Vincent van Gogh, ‘Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear’ – 1889.

Another popular artist whose works grace the walls of any self-respecting Instagram interior designer is Henri Matisse. Perhaps the most popular of these would be the Blue Nudes series, which were created in 1952 during Matisse’s later life. Matisse referred to the last 14 years of his life as ‘une seconde vie’ (a second life) after he became a wheelchair user following cancer surgery. Matisse found that his limited mobility sparked him to experiment in more creative ways, prompting him to begin working on his famous paper cut outs, some of which will feature in the Art Gallery of New South Wales’ upcoming exhibition ‘Matisse: Life and Spirit’. He would direct assistants to place the cut-out shapes on boards from his wheelchair and sketch out shapes using a piece of chalk attached to the end of a stick. Very rarely is Matisse’s disability even acknowledged and when it is, he is categorised as an ‘inspiration’ whose was able to continue his career ‘in spite of’ his disability.

I used to think that disability did not have a place in art history; that the western canon consisted mostly of wealthy white men responding to previous generations of artists and the world around them, but that they were either shielded or uninspired by lowly cripples. I thought that disabled people were absent from the pristine walls of the gallery because their existence was separate from the main narrative of art history.

I have been shown Diego Velázquez’s Las Meninas (The Ladies-in-waiting) (1656) countless times as an art history student. Considered one of the most important works in art history, it is a beautifully complex piece that challenges the viewers perceptions through the use of a mirror and by incorporating the artist into the work. What I have never noticed, or had my attention drawn to, are the two short statured people at the bottom right of the work. Short statured people are actually a regular subject of Velázquez’s and were a common feature of Renaissance courts. Velázquez is noted for portraying them in a more ‘naturalistic’ style, as exemplified in Portrait of Sebastián de Morra (c. 1644). De Morra stares defiantly out of the canvas, his hands clenched in fists perhaps showing his and Velázquez’s disdain for his treatment within the court.

(left) Diego Velázquez, ‘Portrait of Sebastián de Morra’ – c. 1644.

Disabled people have always existed, yet for much of history they have served as objects rather than active participants in their own artistic representation. We can analyse these portrayals in order to better understand how disability has been understood and constructed throughout history, ignoring them only serves to further push disabled people to the margins of society.

In art history disabled people were often used as tools and metaphors in art to portray notions of evil and suffering. Many religious works for example show Jesus healing the blind, lepers and cripples; the disabled people are passive vehicles being ‘acted upon’ within the artwork to demonstrate Jesus’ power and compassion. Disability is represented as a contrast to Jesus’ goodness, as something that is evil and needs to be overcome.

Alternatively, and surprisingly for the context, Francisco Goya’s Mendigos que se llevan solos en Bordeaux (Beggars Who Get about on Their Own in Bordeaux) (1824-1827) shows a disabled man riding in a wheelchair and actively engaged in the world around him. Even the title emphasises his independence and agency. Goya’s own deafness and disability may have influenced his choice to portray the beggar in this way. This is one of the only artworks I have seen of a disabled artist portraying another disabled person and it makes me ridiculously happy. It reminds me that we are here, and we have always been here, and that even in the 19th century not everyone looked down upon disabled people.

(above) Francisco Goya, ‘Mendigos que se llevan solos en Bordeaux (Beggars Who Get about on Their Own in Bordeaux)’ – 1824-1827.

I want to see myself in the art of the past. I want to be reminded that disabled people have always existed and will continue to, and for others to be reminded as well. I want others to look critically at representations of disability and how they shape current perceptions. I want disability to be viewed as a crucial ingredient to many of the beloved artists and artworks in art history, and not obfuscated or ignored.