The past 18 months in Australian higher education has seen destructive funding cuts, 40,000 job losses and revelations of widespread underpayment of casual staff. In this feature, Honi traces how we got to this low point in three parts: corporatised university governance; privatisation of funding; and cost-cutting and efficiency measures.

PART I: CORPORATE UNIVERSITY GOVERNANCE

By Maxim Shanahan

The corporate capture of Australian university governing bodies – generally known as councils or senates – has resulted in leadership bodies unable to guide universities through crises; unwilling to defend the interests of staff, students and their own institutions; and severely lacking in the skills necessary to govern a university.

Appointees to university councils are overwhelmingly drawn from the corporate sector, excluding those from non-commercial backgrounds and, more importantly, those with ‘industry experience’ in higher education and academia. The principle of university self-governance has been steadily eroded through decades of government policy choices and the self-perpetuating cycle of corporate governance.

A deliberate step towards corporate governance

The classical ideal of a university is of a self-governing community of scholars that serves the public interest through serving knowledge. Decades of incremental policy changes have made such an ideal fanciful to staff and students of Australian universities. However, university self-governance still predominates in Europe, and research finds a strong correlation between self-governance and academic excellence.

In Australia, the trend away from self-governance began in earnest with the 1988 Dawkins Report, which described governing bodies – which then ranged from 20-30 seats, with a majority of members drawn from elected staff, students and alumni – as “too large for effective governance.” It criticised elected members for “a tendency to see their primary role as advocates for particular interests” rather than the university as a whole.

In a 2002 report on the higher education sector, which lay the ground for subsequent legislation, then-Education Minister Brendan Nelson said that “Universities are not businesses but nevertheless manage multi-million dollar budgets. As such they need to be run in a business-like fashion.”

The following year, amendments to the Higher Education Support Act were passed, which rationalised the size of governing bodies and required that “There must be at least two members having financial expertise and at least one with commercial expertise.”

Governing body make-up ignores basic principles

The make-up of university councils in 2021 demonstrates the effect this legislation has had in ensuring and entrenching corporate governance of universities.

Across 37 institutions, there are 379 appointed members of university governing bodies (the majority of whom are appointed by councils, while a minority are government appointees nominated by councils). Only 59 of those appointees (15.5%) have ever worked in the tertiary sector (including TAFE). By contrast, 188 members (49.6%) have experience in private-sector corporate management. Only 11 (2.9%) are drawn from the not-for-profit sector.

The constitution of these boards has real-world effects. Where an overwhelming majority of members are drawn from the for-profit private sector, universities are likely to pursue profit and managerialism in the organisation of their affairs. Where a measly 1.6% of members are drawn from the arts, humanities and social sciences, universities are highly unlikely to put up much opposition to government policy which actively discourages enrolment in those areas.

Adam Lucas, a staff-elected councillor at the University of Wollongong, told Honi that “in my experience and that of my predecessors, we’ve seen very limited interrogation by members of most matters brought before Council.” Lucas further questioned why, if corporate board appointees were so fiscally competent, universities continued to cut jobs and courses.

Even when applying their own corporate standards, the lopsided make-up of university governing bodies contravenes a basic principle of governance. Principle no.2 of the ASX’s Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations holds that “The board should…collectively have the skills, commitment and knowledge of the entity and the industry in which it operates, to enable it to discharge its duties effectively and add value.”

For example, 73% of Rio Tinto’s board has experience in the resources and mining sector. Representation is similar across other large mining companies. Likewise, banks’ boards are drawn largely from former bankers, financial industry experts and private equity mavens. Banks and mining companies are ultimately interested in the same goal – increasing profits and shareholder value – yet their governance is tailored to their particular industries.

By contrast, appointments to the governing bodies of universities – which have radically different structures to private companies, and are interested in entirely different outcomes – are made to fit a generic corporate board profile. Bankers and consultants abound; there are more appointees from Macquarie Group alone than there are from arts backgrounds, and career directors stake their turf.

Universities are not-for-profit entities, yet their governance ‘skills matrix’ points entirely towards unabashed profit-making. Universities are interested in the production of high-quality public interest research and teaching, yet people with a basic knowledge of higher education and representatives of academic fellows have been pushed out to make way for Fellows of the Australian Institute of Company Directors.

Alessandro Pelizzon, an academic-elected member of the Southern Cross University council says that there is a “schizophrenic relationship” between governing bodies and universities. He told Honi that “these corporate managers are very effective and very well-functioning corporate managers. But the problem is that universities are not corporations. They might have a corporate structure, but they’re not corporations.”

“What we’re producing is knowledge, not money, and the process of producing knowledge is collective. So the application of the corporate model from the private sector does not easily work. Equating the university to a corporation is like equating the army or the judiciary to a corporation.”

Legislative requirements

Governing body members must fulfil two legislative requirements regarding qualifications and experience.

A self-perpetuating scheme

Firstly, at least two members must have high-level private or public sector financial experience, and at least one must have similar private or public commercial experience. Universities have overwhelmingly interpreted these provisions, perhaps reasonably, to mean financial and commercial experience at large private firms at the expense of public sector experience. The very existence of this legislation demonstrates a hostility to university self-governance in the first place. However, beyond this minimum legislative requirement, university councils have, by their own appointments, become stacked with members from the finance and commercial worlds. Inevitably, corporate governance entrenches itself.

Adam Lucas told Honi that “elected staff members [on councils] are almost invariably locked out of council committees, especially remuneration committees” by corporate-oriented majorities. One result of this has been the skyrocketing pay of Vice-Chancellors, with remuneration committees stacked with private sector appointees aligning executive salaries with corporate standards. More relevant is control over nominations committees. For example, at the University of Sydney, the seven-person committee contains no staff or student-elected members. With such control, nominations are more likely to be made from existing corporate networks, rather than from the academic and education ‘industries’ which are foreign to the committee’s members. In this sense, corporate governance perpetuates itself, leading to a private-sector commercial presence far beyond the legislative minimum.

Functions and values

Secondly, all governing body members are required to (a) have “expertise and experience relevant to the functions exercisable by the [governing body]” and (b) “an appreciation of the object, values, functions and activities of the University.”

According to the legislation, the functions of the governing body are to oversee, among other things, matters of investment and financial accommodation, and to approve its “business plan.” However, it is also required to oversee the university’s performance as well as its “academic activities” and to approve the university’s mission and strategic direction. Where councils are dominated by corporate figures, the university’s performance is reduced to financial indicators and baseless metrics such as rankings, major academic decisions are rubber-stamped by incompetent members. The university’s mission is defined in terms of business and financial outcomes, rather than student experience, teaching quality and research achievement. Furthermore, corporate council members regularly hold multiple directorships, limiting the attention that can be given to understanding the specificities of universities, and the issues which they face. It is highly questionable that governing bodies dominated by CBD CV stackers can have the “expertise and experience” relevant to the non-commercial aspects of university governance.

The same problem applies to the duty to have an appreciation of the object and values of the university. How can council members who have no university experience beyond a decades-prior Bachelor’s degree satisfy this requirement? Previously, these shortcomings may have been balanced out by the presence of higher education ‘industry experience’ and a greater number of elected members. However, the corporate capture of governing bodies has prevented this, redefining the “objects and values” away from knowledge and public service towards profit and corporatisation.

PART II: PRIVATE FUNDING

By Deaundre Espejo

Corporate financial strategies have become the norm for Australian universities. Over the past decade especially, we have seen a rapid withdrawal of government support for higher education, the shifting of cost burdens onto students, and the exploitation of international students.

Through access to unpublished data on the financial performance of all public universities in Australia, Honi tracked the corporatisation of universities’ financial model in the past decade.

Demand-driven funding

In 2012, the Labor government implemented reforms that introduced a ‘demand-driven’ funding model, where universities would receive funding for an unlimited number of student enrolments. The new system was designed to lift participation from under-represented groups and, more obviously, to meet Australia’s labour market needs.

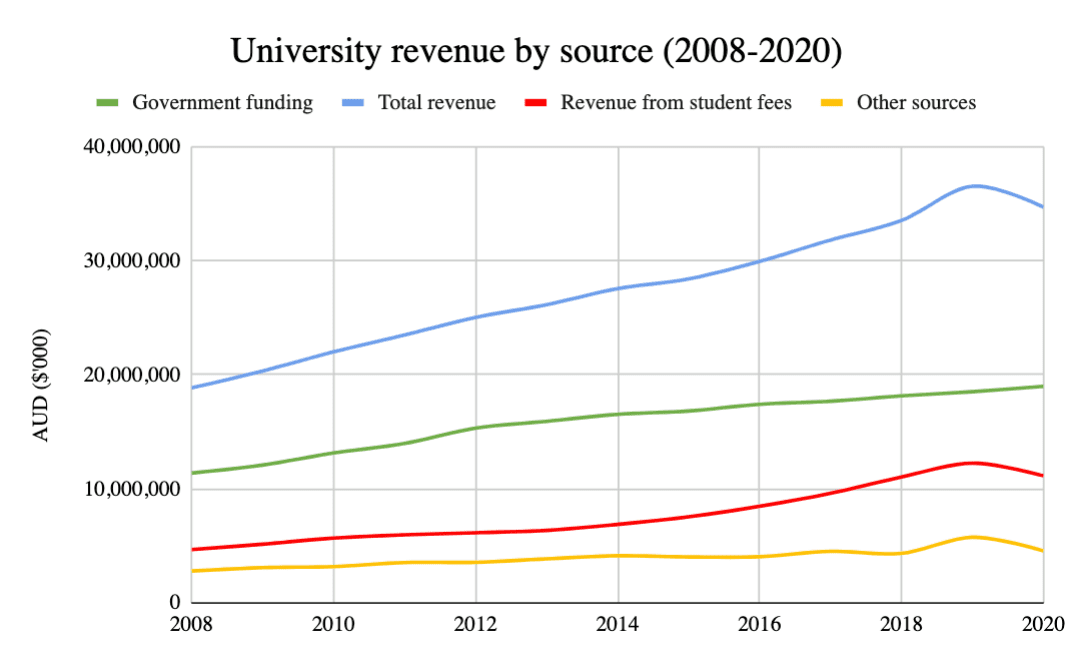

Uncapping funding resulted in a strong take-up of tertiary education. There was a jump in the number of government-supported university places, and subsequently, a steady increase in government funding. By 2017, revenue from government funding had reached $17.7 billion, a 55 per cent increase compared to previous-decade levels.

The growth in student enrolments drew the ire of the Coalition government, who were concerned about the financial sustainability of uncapped funding. They made three attempts at curbing higher education spending, eventually putting an end to demand-driven funding in 2017. The government froze bachelor-degree spending for two years, essentially reverting back to the old “block-grants” system which capped funding for each university.

Universities could no longer rely on the government to fund their operations, so they started to “diversify” their revenue streams — in other words, continue to shift the funding of education from public money to private, mostly student money.

From public to private money

Revenue from student fees — which includes revenue from full-fee places and upfront contributions — has been slowly on the rise for decades. However, there was a rapid growth of revenue from student fees between 2013 and 2019. By 2019, student fees raked in $12.3 billion across the higher education sector and represented a quarter of total revenue.

A significant number of student fees during this period came from international students. Unlike domestic student fees, international student fees are unregulated, which allows universities to set their own fees and hike up tuition. By 2019, revenue from international student fees, as a portion of revenue from all student fees, had risen by 239% compared to 2008. Australia now hosts more international students than any other major country globally.

Now operating in a competitive global market, universities seek to position themselves as “world-class” leaders in “global research and innovation,” despite countless attacks on education. University managers insist that academic staff are ‘selling’ a commodity, emphasising that university rankings, student surveys and other performance indicators are a measure of the quality of teaching, rather than tools for marketisation and commercial gain.

Hiking up student debt

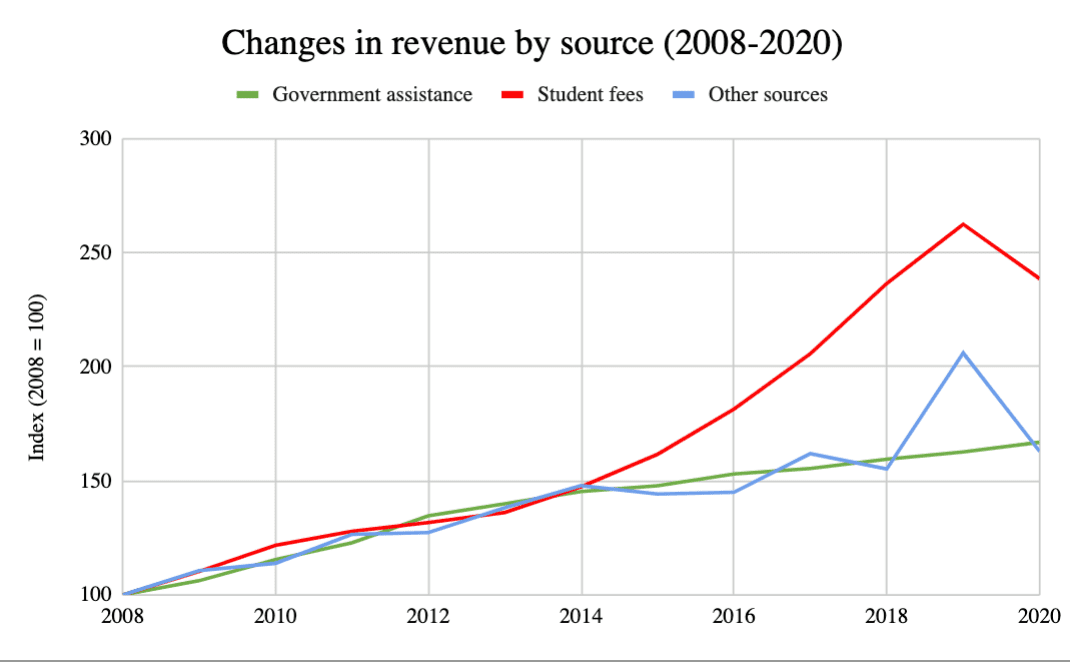

While there was a net increase in government funding in the past decade, this has not resulted in meaningful investment in higher education. Much of this funding comes in the form of student debt, meaning a large proportion is expected to be paid back. Income-contingent loans now comprise over a third of government funding.

By 2020, student loans as a proportion of total government assistance had risen by 138% compared to 2008 levels. In the meantime, meaningful funding in the form of fee contributions Commonwealth supported places and research grants, for example, has plateaued.

Increased debt is another way in which the cost of higher education has been passed onto students, signalling another step in neoliberal decision making.

Impact of COVID-19

COVID-19 and the subsequent closure of Australian borders pushed international revenue streams into crisis. In 2020, revenue from student fees took a $1.1 billion hit, while other more volatile income sources, including investment income and consultancy contracts, also fell by $1.2 billion.

Despite the financial impact of COVID-19, the government did not provide any additional financial support to universities and excluded public universities from JobKeeper payments. They then introduced the Job-ready Graduates Package in June last year, further amping up the cost of degrees for domestic students, particularly humanities and arts degrees.

The new legislation was an unequivocal attack on higher education, further pushing the financial burden onto students. It resulted in a 15% cut in total public funding per student, and a 7% increase in student debt — which university executives have taken sitting down.

Unable to push student and revenue growth, it is clear that university managers are opting to replicate their pre-COVID corporate strategies — searching for new markets, axing staff, and improving greater “cost efficiencies” through drastic cuts throughout the sector. But in the fight for a free and liberatory education, we must oppose the idea that Universities should finance their future through the pockets of staff and students.

PART III: COST-CUTTING AND EFFICIENCY

By Deaundre Espejo and Maxim Shanahan

When we call universities ‘degree factories,’ it is no hyperbolic statement — university leaders have indeed embraced factory-like philosophies of cost efficiency, where each department, course, and worker becomes itemised, ascribed a financial value and is constantly forced to justify their place within the institution.

As a direct result of funding shortages, we are seeing three ways in which university operations are fundamentally changing: increased managerialism, rising staff to student ratios, and the casualisation of the workforce.

The budding middle manager

Performance management — the use of targets and metrics in order to improve staff ‘efficiency’ — has become a central feature of Australian higher education. With performance indicators such as drop-out rates, graduate employment, and the number of publications being increasingly tied to government funding and international rankings, universities have embraced corporate managerialism in order to maximise their output.

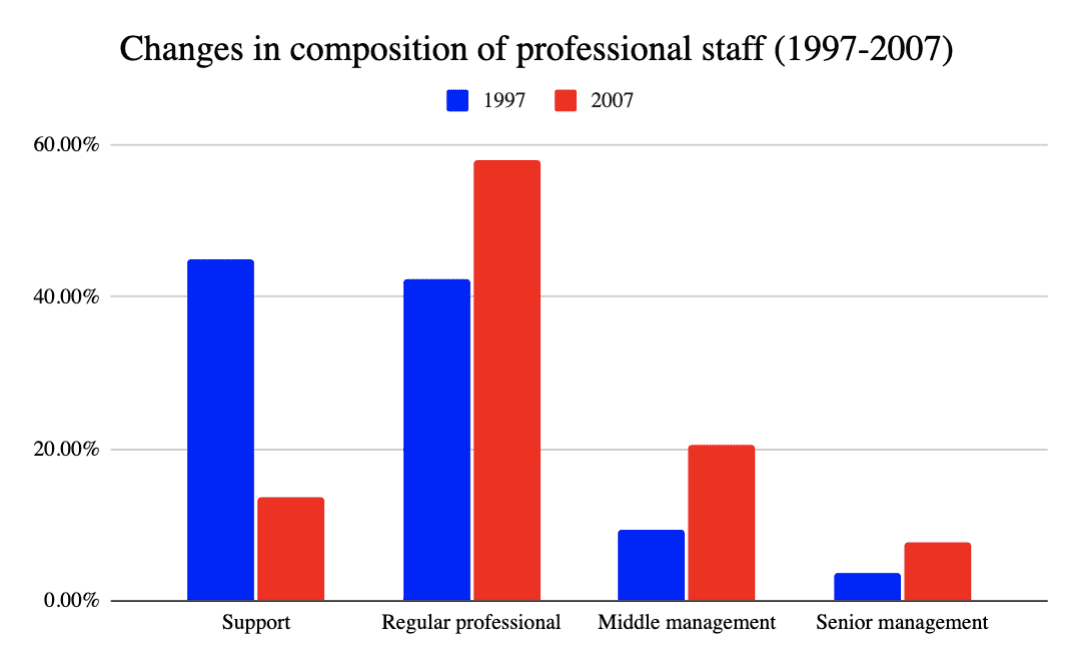

The proportion of non-academic staff across universities has remained relatively stable in the past decade. However, there has been a noticeable growth in management-rank positions across the sector. In 2017, the proportion of middle management positions had grown at the highest rate (122%) compared to 1997 levels. The proportion of senior management roles also increased at a considerable rate of 110%.

In marked contrast, the proportion of support roles declined significantly (70%). The number of regular professional staff has grown, though at a slower rate than management positions.

As a result, the cost of maintaining the non-academic workforce at Australian universities has slowly but surely increased. We now see a higher education system led by HR, operations and marketing managers, leaning over the shoulders of staff to ensure they perform profitably.

Poor financial management

Despite increasing managerialism, poor financial management at universities has failed to convert the surpluses earned between 2008 and 2019 into sufficient reserves in the event of a financial crisis. In 2020, the university sector still recorded a surplus, but it was at its lowest in at least ten years. Operating results across the sector were a total surplus of $680 million, hardly enough to absorb the losses of COVID-19.

University executives are paid exorbitant salaries, while positioning themselves as acting in the interests of staff and students. In 2020, Vice-Chancellors across 40 universities collectively took home $31.18 million, a modest decrease compared to the $36.74 million of the previous year. Additionally, over a third of ex-officio university council members across Australia earn a salary over $500,000.

Soaring staff to student ratios

Staff to student ratios – another key indicator of university performance – have suffered a steady rise in Australia since 2017. Data from Times Higher Education rankings from 2017 to 2022 shows that the average number of students per academic staff member (including casuals) has increased from 28.1 in 2017, to 32.2 in the 2022 statistics.

At UNSW, there was a 50% rise from 26.3:1 in 2017, to 40.5:1 in 2021. At Macquarie University, that figure rocketed from 32.8:1 to 69.6:1 over the same period.

Australia’s figures stand in stark contrast to the situation in the United Kingdom, where the average has hovered around 16:1 for the past decade. By far the UK’s worst performing university on this metric – the Open University, which is a distance education provider – had a ratio of 31.8:1, lower than the entire Australian average. Australian universities also perform significantly worse on staff to student ratios than American universities. The US’s worst institution for staff to student ratios – the University of Central Florida – had a ratio of 36.3:1, better than many of Australia’s best-renowned universities.

The low regard with which universities increasingly view their academic operations can be seen in the precipitous increase of academic casualisation and the concomitant ills of poor conditions, insecure work and wage theft.

Casualisation on the rise

Much has already been said about the scourge of casualisation in Australia’s universities. — another way in which universities have kept costs down.

As Jeffrey Khoo explains, it is difficult to calculate the number of academic casuals employed in Australian universities. However, it is generally estimated that between 50% and 70% of academic university staff are casual employees.

Casuals are easily exploited: universities do not have to provide leave entitlements or basic conditions; they are not paid during non-teaching periods; and the piece-rate method of payment forces casuals to provide unpaid labour marking papers, developing materials and responding to students’ queries beyond their allocated hours. Indeed, on Friday the Fair Work Commission said that they were “quite concerned” about “large-scale underpayment” of casual academics.

The re-employment of casual academics is often predicated on the entirely arbitrary measure of student course and teacher evaluations, perpetuating underpayment as sessional staff perform unpaid work to attempt to meet performance guidelines. If casuals were to work only to their paid hours, then acceptable standards of teaching, marking and course preparation simply would not be met.

The casualisation of Australia’s academic workforce is reminiscent of the most distasteful corporate practices: reducing expensive full-time and part-time employees while loading up on cheap casual labour, skimping on conditions, staff wellbeing and basic employment rights in order to save a few bucks. In their turn to casual labour, universities have demonstrated that they are willing to sacrifice teaching quality, academic outcomes, and staff conditions in order to increase student output and lower costs.

A depressing picture for students

Against the backdrop of a performance-driven culture, Australia’s staff to student ratios and rampant casualisation paint a depressing picture. Students know this well; lumped into outrageously sized Zoom seminars, dulling any ability to form relationships with academics and participate in meaningful class discussion.

Universities’ embrace of post-COVID ‘blended learning,’ culling of ‘underperforming’ courses and continued job cuts will only see ratios continue to rise. The rise of staff to student ratios and casualisation is indicative of universities’ willingness to cut back on the costs of their core ‘business’ – employing academic staff to teach and research – while maximising their income through the output of students.

***

Note: The print edition of this article included Jeffrey Khoo’s ‘Creative Accounting: NSW public universities must be more transparent with employment data’ which can be read here.