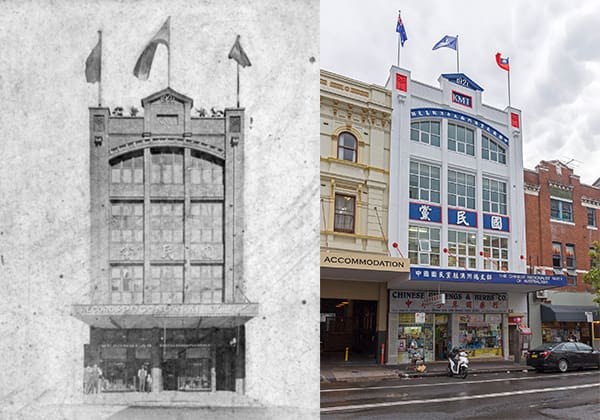

When walking along Ultimo Road heading for Chinatown, one will encounter a white and blue building that stands apart from its surroundings. The building was the headquarters of the now defunct Chinese Nationalist Party of Australia (CNPA), a foreign branch of the previous ruling party in China. To the untrained eyes, the building is simply an architectural curiosity. However, for Chinese Australians, it is a monument to their unique political and cultural identity.

Chinese Australians have been seeking to build a home, a “jia”, in this land since the birth of Federation and the White Australia Policy in 1901. Many were inspired to fight for their place by the anti-imperial and democratic republican project playing out in China under Sun Yat Sen.

The CNPA was born during this era. The goal was to create a sense of belonging for those that stayed behind after the Gold Rush, united by a common language and culture. It also sought to build a diverse community that was open to all, with no gender bias nor discriminations against clans, affiliations, and ethnicities.

The party also contributed to the anti-imperial cause in China, which had hoped that change in the Mainland would dispel the culturalist attitude against which the White Australia Policy was established: a belief that the Chinese culture was ‘backward’ due to its imperial history. In research by Mei Fen Kuo and Judith Brett, it was estimated that the CNPA ranked third for overseas affiliate donations to the Republican forces.

The building was purchased during this period, in 1921, to serve as the headquarters of the party. With it, members worked tirelessly to improve Chinese Australian welfare. Chinese newsletters were published to keep the public informed, many were assisted in finding jobs, some formed unions, whilst the party held events and picnics to help recreate a semblance of home in Australia. These initiatives sowed the seeds for an idealistic, community driven future.

Unfortunately, in 1925, Sun Yat Sen passed away and with that, there were seismic changes in the fortunes of China and the Chinese-Australian community. His successor was generalissimo Chiang Kai Shek who decided to forgo the democratic effort for which many had fought. Under him, thousands were executed in purges against Communists and labour organizers, and the Chinese political landscape was forever changed.

This shift was reflected in the CNPA as well, with the Chinese-Australian efforts against White Australia suddenly turned against its own. According to John Fitzgerald, a party purification committee purged around 3000 members from the Sydney branch — roughly 50% of the membership.

This moment in the CNPA’s history marks a profound conflict within the Chinese-Australian community of the time. It forced them into the two opposing camps: pro-Nationalist Republicans against Pro-Communists. A fellowship of shared language and culture was no longer sufficient to keep the peace.

From 1928 onwards, the Sydney headquarters was turned into a spying station against ethnic Chinese in Sydney. Files were kept on those who were critical of the government in China and the CNPA went from fighting for the rights of Chinese Australians to betraying the community to protect a distant mainland elite.

As the world marched solemnly into the 1940s, great civil unrest continued throughout China. Chiang’s Chinese Nationalist Party saw its demise during this period, fleeing to Taiwan in 1949. Power was then transferred to the ruthless Chinese Communist Party, under which political and class persecution became a norm.

Despite unrest in the mainland, conflict did not further seep into the Chinese-Australian community at the time, as thoughts of consolidation now occupied their minds. The community became more diverse, helping refugees from all corners of Asia to escape political persecution at home. Broad ethnicity and shared trauma became a new uniting force. Many were given a home in Chinatown and sustained by a community largely healed from the previous decades of division.

An organised effort against Chinese deportation, a product of increased scrutiny under the White Australia policy, featured heavily as well. Though major cases were lost, small cases led by CNPA affiliates, such as Martin Wang, were able to successfully prevent the deportation of five people in 1949.

Out of the ashes of conflict, a community was seeing itself heal and thrive. Under this rehabilitation, the CNPA also reclaimed its role as a community institution. Gone were the days of espionage and surveillance, the CNPA began to organise sporting competitions for youths and adults.

The building stands today as a mark of reconciliation for the thriving community. Many were without family, fleeing persecutions, or simply lost, but all saw a home in Australia. Eventually, what they had dreamed, had become a reality. In 1957, Chinese people with fifteen years residence in Australia could apply for naturalisation. White Australia was officially abolished in 1973, allowing this land to be called home, a “jia”, for Chinese Australians.