In this feature written during the week of the Sydney Film Festival, Honi Soit spoke to former members of campus film societies to discover the pivotal role of students in championing film as a serious art form, amidst a Cold War context that cast suspicion on the film society movement as a communist threat.

There is nothing quite like the collective experience of watching a film in a dark theatre with hundreds of strangers: witnessing cantankerous walk-outs; the belly laughter of the person in the front row; an entire room jumping in their seats and holding their breath at the same moments. There aren’t many settings in our fast-paced world of commercial content that demand our undivided attention in the way that a good film does.

For the past two years of lockdowns, the Sydney Film Festival has been sorely missed by many annual festival goers. It’s good to finally be back at the State Theatre. On Friday, after watching a perplexing screening of Memoria and entering the art deco foyer, I found my friends already in disagreement about the film. Some fell asleep out of boredom, others were entranced by the sound design, but most of us just wanted to go to Sweeney’s Hotel for a drink. Thus has been the tradition for festival goers who are regulars at Sydney University Film Society (FilmSoc) during my time at uni.

Unlike other realms of student culture such as the SRC and SUDS where there are well-recorded and oft-told histories of generations past, the history of campus film societies is largely unwritten, scattered across the memories of the people who experienced it first-hand. Beyond a few old screening lists donated to FilmSoc, I had no understanding of the trailblazing history of film societies at our university until I began to research them. Hidden away in the Uni archives are two boxes of material on the defunct Sydney University Film Group (SUFG) and its rival Sydney University Film Society (SUFS). What I found in those boxes uncovered a history more wonderful and rich than I had ever anticipated.

Film as an art form

It was not until 1980 that Film Studies was taught in an academic context at USyd. For much of its history, film lacked recognition as an artform and students who were passionate about the study of film could not pursue it within their degrees. The formation of SUFG as an offshoot of the Visual Arts Society in 1947 fulfilled this intellectual niche; not only screening films but also holding lectures on their aesthetic, sociological and technical aspects, forming study and discussion groups, and publishing critical reviews and notes on all the films in a bulletin each term.

SUFG emerged at a time of immense political transformation: the Cold War was fast becoming front-and-centre of mind, and headlines like “FREE SPEECH DESPITE COMMUNISTS” were splashed on the cover of Honi Soit. At the first General Meeting, under the presidency of Chair of Moral and Political Philosophy A. K. Stout, it was decided that the Group’s objective was: “To promote within the University the study of the film as an artform and as an educational medium, and to raise the critical standards of University film audiences.” Stout’s advocacy for the cause of film was buttressed by his respectability as an academic, possibly one of the first in Australia to champion film as a serious medium distinct from theatre and literature.

Core members of SUFG took their commitment to its tenets very seriously, though with a growing membership of students drawn by the free screenings, not everyone embraced it. In a 1956 meeting for example, a member complained that films shown such as Battleship Potemkin “were not sufficiently entertaining,” to which the President promptly read out the constitutional clause relating to the scholarly aims of the Group. It is difficult now to imagine such an attitude appearing as anything but pretentious. But in the late 50s, SUFG was one of the largest societies on campus, with a membership of around 800 or 900 at a time when total enrolments were in the 8000s or 9000s. It was a small world.

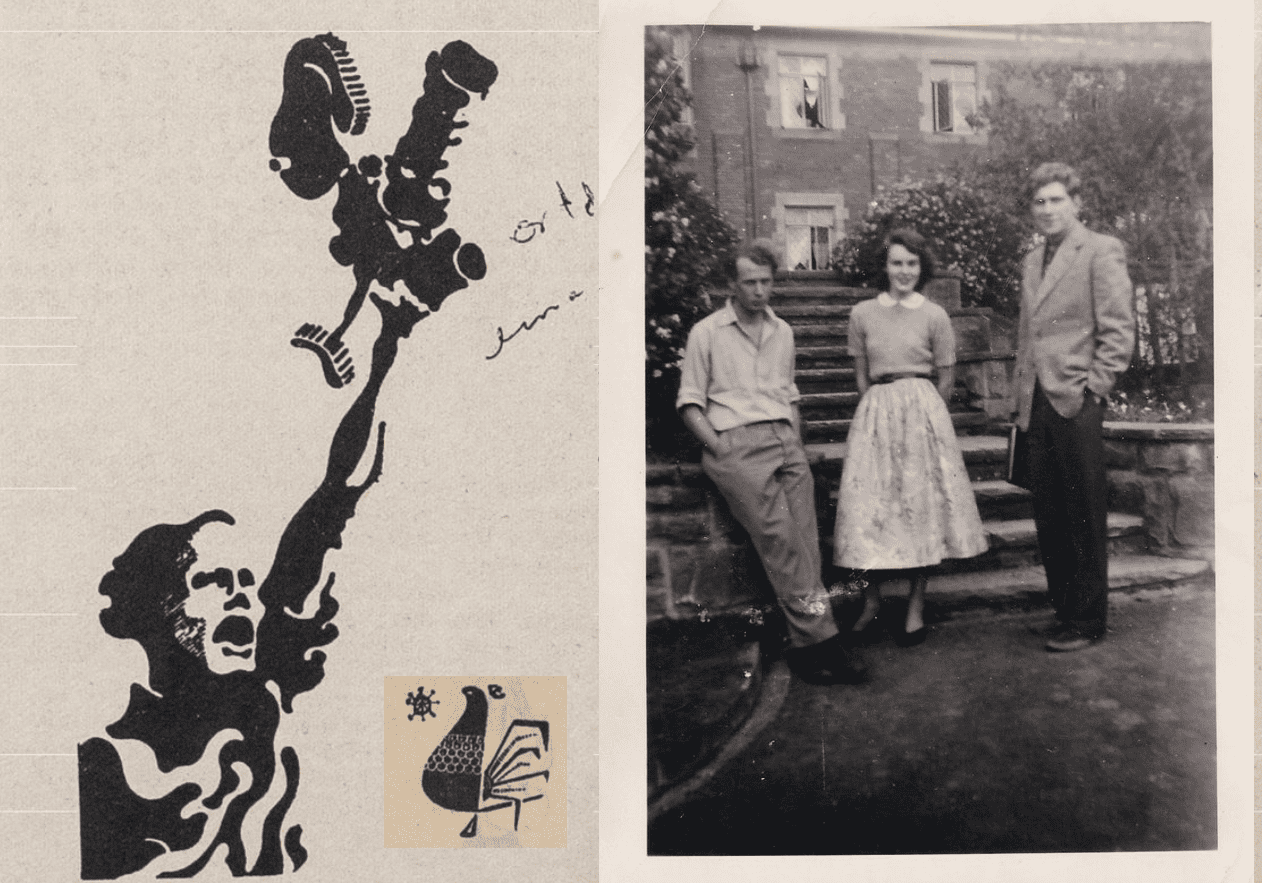

SUFG’s mission of combatting the perception of film as entertainment by showing the University that it was the “greatest living artform of the 20th century” distinguished it from rivals, SUFS, which predated SUFG. Consisting primarily of Engineering students who mucked about with the projectors in the old Union Hall, SUFS showed fairly commercial Hollywood films on 35mm and were interested in the technical aspects of film more than its artistic potential. Meanwhile, the base of SUFG was the Wallace Theatre, which had 16mm projectors installed and was used for their Friday evening screenings. For decades, Honi Soit editions included notices for on-campus film screenings from both societies; the SUFG ones marked by their curious logo of a rooster.

Amid concerns that a section of SUFG’s audience was unwilling to engage with non-commercial cinema and failed to differentiate their mission from that of the SUFS, SUFG wrote a manifesto of sorts in a March 1957 Bulletin, entitled ‘NOTES TOWARDS THE DEFINITION OF A FILM SOCIETY’. They stated their belief in “cinema as a serious means of communication and artistic expression, just as capable as the printed word,” noting that their academic approach to film “does not necessarily exclude entertainment, but entertainment takes a decidedly secondary place.” Henceforth, SUFG inaugurated a series of talks in order to encourage ordinary members to understand the society’s sophisticated aims.

The intensity of the commitment displayed by the students organising these events is difficult to imagine today, where most students are busy juggling study with work, but it ultimately paid off, leaving an indelible mark on Australian film culture and criticism. The post-WWII upsurge in the film society movement across Australia was also a testament to the power of students and graduates to self-determine their own learning, at virtually no fee, in lieu of a university course. In a 1959 Honi article titled ‘The Art of Canned Entertainment’, Geoffrey Atkin wrote that “film is treated as the cinderella of the art forms” at the university, and that “the study of film is left to the hands of voluntary workers who constitute the film society movement. It is to the credit of these people that such a keen interest is now taken in film appreciation.”

A free-thinking student culture

Earlier this year, I spoke with one of the figures in the film society movement at Courtyard Cafe: historian Jim Masselos, who was involved in SUFG between 1957 and 1960 and was President of the SUFG committee. He reminisced about the excitement surrounding the marvels of cinema and the sense that everything was happening after the war, which had created a backlog of films: “I remember my first year coming up to uni, and the Film Group was just showing all these incredible movies … They did a round of all the great cinema classics, and it just blew my mind as a young kid.”

During Masselos’ time in SUFG, everyone subscribed to the British film magazine Sight and Sound, as well as Cahiers du Cinéma once the French New Wave rolled in. SUFG was anxious to get funding to bring people to Australia for talks, and invited British documentary filmmaker and critic Paul Rotha to introduce a film in the old Union Hall. Masselos said “I remember I introduced him and I was tongue-tied, he was this incredibly important person.” Interested in the educational potential of documentaries, SUFG was the beginning place for future documentary filmmakers and critics Judy Adamson, Ian Dunlop, Ian Klava and John Morris.

Before Masselos came onto the scene, the most significant thing SUFG did was rediscover and rescue the silent feature film: The Kid Stakes. Shot in Sydney in 1927, The Kid Stakes was a humorous film about the adventures of rival gangs of kids entering their pet goats in races. The committee of SUFG was determined to preserve it in its original condition and brilliantly reconstructed the print to be lodged in the National Library (there was no thought then of a film archive).

The most salient parts of my conversation with Masselos were not only the picture he painted of an energetic film culture, but also the stories he told of student life more broadly. As one of the staff for Honi Soit in his first year, Masselos was surrounded by associates of the Sydney Push: Clive James and Robert Hughes both published poetry in the paper. Masselos told me that “those days were really quite extraordinary. You know, in the late 50s and 60s, there were lots of extremely brilliant people, in all sorts of ways there was a brilliance in creating things.”

Masselos recounted receiving a scolding letter in Honi from now-famous art critic Robert Hughes over a critical review he wrote of Hughes’ Dada art exhibition, which he said was slightly “Freudian.” Also of interest was how Manning House was for women only then, and male students would go there for coffee but had to leave at noon: “If you didn’t leave an attendant would turn up with a big bell to your ears until you got out.”

Many SUFG members studied Philosophy “because it was a trendy subject to do and it was seen very much as the central discipline in the Arts,” Masselos said. The Department was headed by controversial philosopher and free-thinker John Anderson, whose criticisms of Christianity and patriotism had a strong influence on the Push, and made him the target of attacks from State parliament and the media. The University Senate censured Anderson, creating A. K. Stout’s position as Chair of Moral and Political Philosophy with the intent to counterweight Anderson’s influence. Yet the two got along well, with Stout reportedly saying that “[Anderson] went on corrupting the youth just as much as before, and damn it all, he corrupted me too!”

Returning to Stout’s connection to the SUFG, Masselos joked that “Stout was a short man and he couldn’t see if he sat in the centre of the stalls, so he would always sit on the sides of the theatre … [In Moral Philosophy] you’d be taught things like x is good but y is better, and with Stout the joke went: beer is good but Stout is better.”

The birth of the Sydney Film Festival

From 1954 to 1968, the University of Sydney was home to the Sydney Film Festival. Now a major cultural event that attracts hundreds of thousands of attendees and international attention, few are aware that the festival only came into being because of the work of SUFG.

The Sydney Film Festival was not the first festival launched by SUFG. In 1949, it held one of the earliest film festivals in Australia, which ran over six nights at the university for free. Organised by Peter Hamilton, the vision for the festival was aligned with post-war liberal humanist values of international sympathy and understanding. A 1949 Honi article written to promote the festival titled ‘FILMS… and on the house!” argued that film’s unique feature “is that it transcends the barriers of class, creed, and nation … It is because of this universality of appeal that the film can be such a force for understanding and the development of tolerance in the world.” But it was the ‘40s, and the international sympathy represented by the festival extended only to France, Germany, Sweden, other English-speaking countries, and the USSR.

The humanist vision and organisational skills developed through the early SUFG festivals provided the foundations for the first Sydney Film Festival. A committee was created out of the Film Users’ Association (FUA) — a body representing all the film non-theatrical interests in NSW — which included Stout, filmmakers John Heyer and John Kingsford Smith, and Federation of Film Societies secretary David Donaldson, who became the first director of SFF. In our email correspondence, Donaldson credited Hamilton as a “multifaceted near-genius” for laying the groundwork for the festival and “modestly add[ed] that SUFG people, notably Ian McPherson but the whole crew, were the only film society people in Sydney with the energy and know-how to put on large events.”

The daunting challenge of holding the first Sydney Film Festival within the University necessitated collaboration between rivals: art-focused SUFG and technology-focused SUFS.

I spoke to a former member of SUFS, Peter Aplin, over email: “When SUFG decided to mount the first Sydney Film Festival, they naturally turned to us for technical support which we were very happy to provide. I joined the SFF committee to liaise and the whole thing became a joint venture.” Admitting that there were disagreements as “some members of SUFG were a little contemptuous of the mere mechanics of showing movies while SUFS members were familiar with sourcing film, advertising and selling tickets,” Aplin said that it was an astonishing achievement looking back. “The fact is, neither group could have succeeded alone.”

Staging the festival at the University rather than at a commercial cinema minimised costs for the organisers and also allowed them to avoid the conservative influence of the Australian film censor. Screenings were held at the Wallace Theatre, the Union Hall, an annexe to the New Medical School, the Old Teacher’s College and later at the Great Hall.

In the digital Living Archive of Sydney Film Festival are stories from attendees over the years, recollecting the joys of wandering through the University and stopping to chat about films. The programme was designed so that it was possible to see every film screened if festival goers followed the track properly, like a giant campus maze. As Ross Tzannes put it: “The idea of being able to picnic between the films and to be able to discuss films with other people in a pleasant setting like that created a much more relaxed atmosphere than the frenetic timetable that modern-day festivals seem to demand.” On the other hand, Richard Keys recalled there being “a certain amount of chaos, as subscribers rushed from one venue to the other between sessions,” which will resonate with anyone on a tight schedule during this festival season. One festival goer travelled all the way into the University on an overnight steam train, enticed by the “promise of something other than Hollywood”.

Despite the organisers’ best efforts, the quality of the venues and projection was subpar, and the seating was almost unbearable, but they were prepared to suffer for their art. Brenda Saunders remembered “the trace of rotten-egg gas wafting over the raked seating in the science lecture room: Bunsen burners and tripods outlined against the grainy images of classics.” Moreover, some imported film prints had no English writing, causing the projectionist to screen the reels for Seven Samurai out of order. They even dropped two reels out to shorten the film one night, worried that there’d be no transport for people to get home by the time it finished; though the missing scenes did not go unnoticed. Held in mid-June, the venues became chillingly cold in the evenings. Joan Saint recalled watching a film until three in the morning in a freezing Great Hall: “We decided it was a waste of time to go to bed, so we went up to the Cross and had breakfast. And then we came back at 9 o’clock to continue.” Everyone also smoked at the screenings, and in a letter to Honi in 1962, one student even called for a referendum amongst the student body for the Union to provide an ashtray for each seat in the theatre.

ASIO surveillance and the film society ‘Red’

Coinciding with the dominance of anti-communist political sentiments in the Cold War, the development of small film societies across the country aroused security concerns in the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO). The subversive potential of alternative cinema in particular, which countered the capitalist ideology of Hollywood industry, was perceived as being associated with left-wing movements. ASIO was concerned that these non-commercial film societies and festival committees were being infiltrated by members of the Communist Party of Australia (CPA), and that the screening of Soviet films wasn’t just for artistic appreciation, but as a tool of propaganda.

Anti-communist fervour emerged not only from external government agencies, but internally in the film society movement. This was demonstrant in Neil Gunther, secretary of the Film Users’ Association, who wrote an article in 1951/2 called ‘Goodbye Mr. Red’ in which he advised film societies to expunge communist members. Steeped in the language of McCarthyist hysteria, Gunther wrote that “the film society ‘Red’ may be quickly recognised even though he doesn’t wear his hammer and sickle on his sleeve … He’ll reel off yards of twaddle about Soviet film directors like Eisenstein and Pudovkin, and do his best to convince you that seeing films directed by them is a rich experience.” Gunther believed that film society communists thrived through discussion groups and journals, which would make almost every intellectual in the movement suspect.

Commenting on Gunther’s article, Donaldson remarked that “we laughed at the time but he was deadly serious,” though credited him for being a great film worker. Years later, Gunther’s political obsession would cause a major split in the Film Users’ Association and irreparable fractures in the movement. Donaldson was in Canberra perusing 16mm film prints when he visited the secretary of the Canberra Film Centre, who had received a letter from Gunther “about the menace of communism in the film movement and a plea to defeat it in the upcoming AGM of the FUA.” The SUFG minute book from 1954 relates what followed: the Film Users’ Association was rushing through a new constitution to include a clause that nominations for positions on the council must be accompanied by a statutory declaration that the member is not a member of the Communist Party. At a Special General Meeting, SUFG passed a motion objecting to the draft proposal. The AGM of the FUA was heated: Sydney University delegates walked out publicly and seceded from the Association, with record of Donaldson mentioning the “iniquitous things” that had been said about SUFG in the following meeting’s minutes.

From 1954 to 1959, ASIO kept a dossier on the activities of SUFG which was opened to the public with exception in 2003. However, parts of it remain restricted because of concerns it could damage Australia’s security interests and disclose the existence of a confidential source of information. This indicates that there were political informants within SUFG. The surveillance was possibly aroused due to the group’s disapproval of the ban on communists in the FUA or their screening of Soviet classics, which security agencies feared would create a line of contact between Soviet diplomats and Australians.

In order to acquire 35mm and 16mm prints to show at the Sydney Film Festival, a contingent of organisers would board the train to the National Library in Canberra. On one occasion around 1953, in search of the legendary but inaccessible Sergei Eisenstein film Ivan the Terrible, Donaldson and McPherson daringly paid a visit to the Soviet Embassy. There they met the arts officer, Vladimir Petrov, who apparently knew nothing of Eisenstein and was useless, but soon afterwards became a household name for defecting from communism and gathering information for ASIO on Soviet espionage operating out of the Embassy. Donaldson told me he guessed that his visit to Canberra would have been noted by ASIO. Later, following the FUA split, SUFG finally obtained a 16mm print of Ivan the Terrible from London that had “slipped away from Stalin’s grasp” and showed the film that everyone had read about but never seen. “I now realise what a dreadful print it probably was but my god it was a blinding experience,” Donaldson said. “Great days, but that would have confirmed Neil Gunther’s (and I dare say ASIO’s) fearmongering about the commo threat.”

ASIO’s interest in the Sydney Film Festival deepened in the 1960s, when cultural exchange with the Soviets resumed. Several individuals in the SFF committee had ASIO dossiers about them, and festival directors such as Ian Klava and David Stratton had some of their conversations recorded and put on ASIO’s files. The effect this routine surveillance had on the work of left-wing filmmakers, particularly the minority who were actually communist, damaged the nascent film movement’s resistance to the insularity of Australian culture.

Honi Soit has requested a copy of the ASIO dossier on SUFG, though unfortunately due to the impacts of the Canberra lockdown it will not arrive until after the publication of this article.

Radical cinema in the ‘70s and the final days of SUFG

In the 1970s, the political cinema of the French New Wave was all the rage, and SUFG played the first Sydney screenings of films that were rejected by cinemas for commercial reasons: Jean-Luc Godard’s Bande à Part, Alain Resnais’ Je t’aime, Je t’aime, Jacques Rivette’s La Religieuse, and more. It also held programmes like ‘Third World Cinema’ in 1972 and ‘Radical Theatre’ in 1973, showcasing politically revolutionary films about workers’ struggles, civil disobedience, and liberation from colonial violence. These series of alternative films appealed to a politically radicalised student body who were challenging authority and Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam War.

Meanwhile, the long-time rivalry between SUFG and SUFS was imbued with a sense of youthful irreverence characteristic of the ‘70s. A SUFS document called ‘NEWSPELL’ from 1971 included a cartoon crest of a rooster atop some spools of film, parodying the SUFG logo. The document is far more jeering in tone than anything produced by SUFG, joking that the paper upon which it was printed “is easily dissolved in most sewerage systems if you feel that you are compelled to use it thus,” and making insulting reference to “stiff competition from the cads of S.U. Film Group”. It is clear which society took themselves more seriously.

In 1977, SUFG and SUFS reached an agreement to screen films in the Union Theatre on a commercial basis in order to raise revenue for their activities, and combined as the SU Screenings Committee for a number of years.

Sadly however, the energetic spirit and organising flair of SUFG faltered after 32 years of activity and it ceased to exist. The final screening of SUFG was held on 29 October 1979, a double bill of the Italian film Allonsanfàn and French film Les Biches, wrapping up the term three programme ‘Anarchy 1933-77’. Bruce Hodsdon, who co-curated that final programme, told me there were no issues with the Group’s financial position, but that they had trouble interesting a new generation of students to take over running the operation. Another society of film buffs formed, Hodsdon transferred all the finances to them, and the National Library of Australia made a payment for SUFG’s film prints to be made available in their collection.

***

In my first semester of uni, sitting on patches of grass along Manning Rd with friends watching Un Chien Andalou between tutorials and exploring the DVD stacks in Fisher, I fell in love with film. Our friend group attended every FilmSoc screening we could, beginning with the fantastic Dr Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. I had not taken a strong interest in films before, but going to the contemporary FilmSoc and talking to people on the weekly pilgrimage to the Flodge afterwards opened my eyes to another world of art.

Now the only operative film society at the University, the current iteration of FilmSoc represents a halfway point between SUFG’s legacy of screening art films with the unpretentiousness of the original SUFS. Thankfully, FilmSoc’s golden rule is that no Quentin Tarantino films can make it onto the screening list (because everyone’s already seen them). Instead, the unheard of and unorthodox are embraced: every Wednesday or Thursday evening screening promises to delightfully expose you to film movements you’d never heard of before.

The digital age has meant that there is no need for the society to build relationships with distributors to import film prints, and while this is more efficient, it is something of a loss. In the early days, as Masselos put it: “to run a Film Society, a lot of the work seemed to be in carrying rolls of film around and in distributing it.”

Now, on Wednesday or Thursday afternoons you’ll see FilmSoc members carrying boxes of pizza on their way to Old Geo or Heydon Laurence. A lot has changed over the years, but the magic of being a student sitting in a lecture theatre for a free film screening will never pass.

With thanks to Jim Masselos, David Donaldson, Peter Aplin, Bruce Hodsdon, Alan Cholodenko and the University Archives.