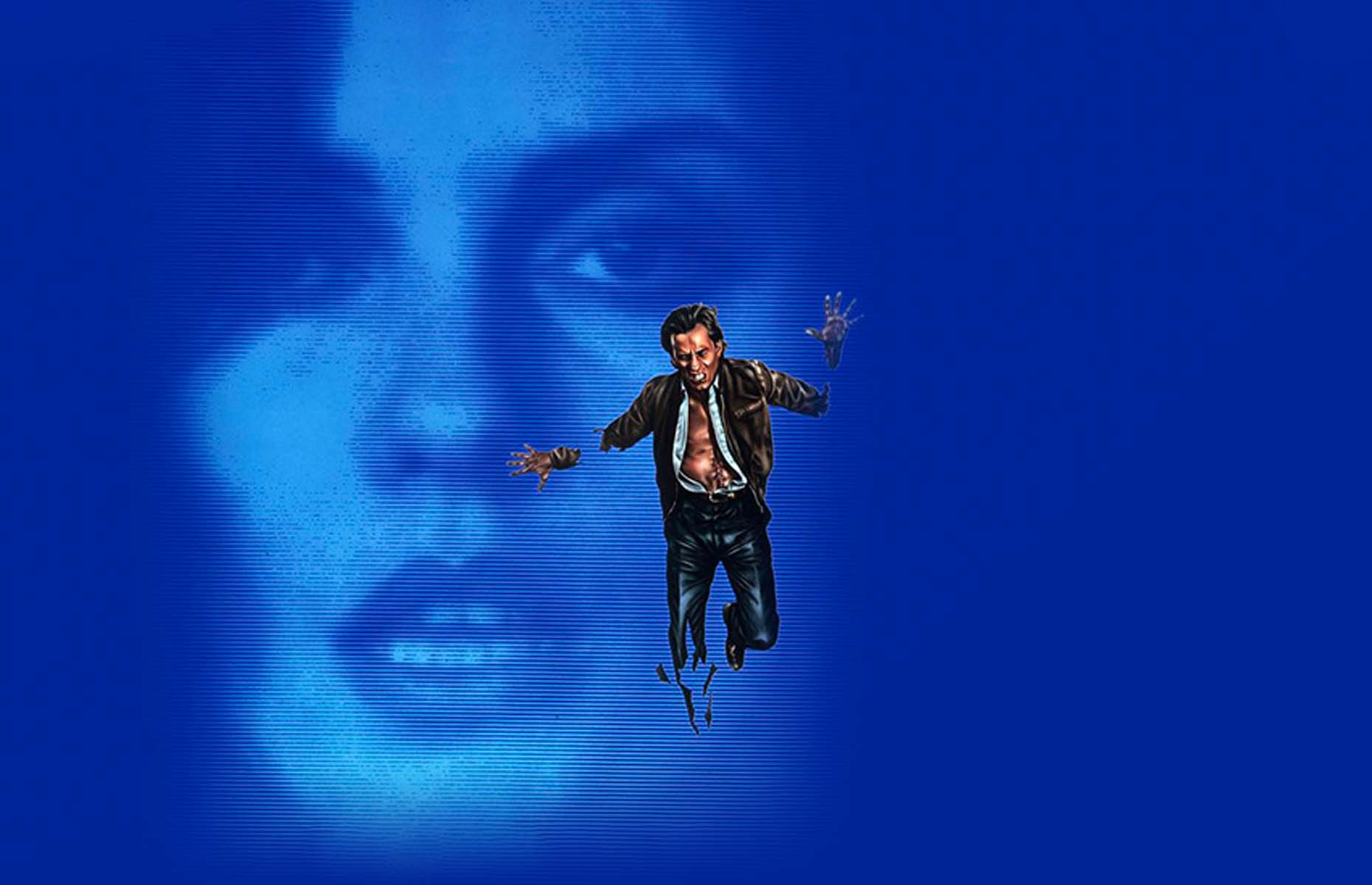

In a dark apartment, Max Renn gets on his knees in front of his television set. It’s breathing. Throbbing. Heaving. Hypnotised, he leans forward and kisses it, his head passing through the screen. He surrenders himself to the box and lets it envelop his skull. First it controls your mind, reads the film’s tagline. Then it destroys your body.

Videodrome was released almost 40 years ago, yet the neon-laced psychological thriller is perhaps more relevant today than it was in 1983. We follow Max Renn, a sleazy TV exec whose personal and professional life is consumed by and intertwined with television. One day he encounters Videodrome, a plotless snuff-show being broadcast from an unknown source. Upon viewing Videodrome, Renn’s world grows increasingly surreal as he experiences bizarre hallucinations and mind control. The lines between reality and television blur. Without spoiling the film, Renn finds himself at the mercy of television, the only domain he thought he had control over.

Watching Videodrome today, it’s easy to see the parallels between television and social media. Both are flashy, kaleidoscopic mouthpieces for capitalism and consumerism. Yet at the forefront of social media is a new concept – surveillance capitalism. For the uninitiated, it refers to the practice of software companies tracking their users’ data to influence their behaviour.

The goal of surveillance capitalism, according to Shoshana Zuboff (who coined the term), is “to automate us… to eliminate any possibility of self-determination.” This, combined with the detrimental effects of social media on mental health, provides ample justification for corporations like Meta (Facebook’s parent company) to be condemned. Yet Silicon Valley’s mega-rich CEOs soldier on, monitoring our data (allegedly with our loyal consent), and exploiting our deeply-rooted dependence on them to make us more like Max Renn – helplessly submissive to their agendas.

I have a love/hate relationship with social media. I hate surveillance capitalism. I hate having my privacy breached. I hate Mark Zuckerberg. But I need social media. I need the messages. I need their constant affirmation and connectivity. I need to see which stage of grief Kanye is at now. I hate to admit it, but I am Max Renn. I would get on my knees for social media.

Two years of lockdowns and gathering restrictions swept the university experience online, and clubs and societies along with it. Whichever groups hadn’t sold their souls to social media before 2020 had to enter the ether or risk getting left behind. Today, you’d be hard pressed to find a society or club on campus that isn’t in part reliant upon Meta to operate. Facebook events, Instagram stories, and Messenger chats form the bedrock of USyd social life. “Television is reality,” a character from Videodrome tells Max Renn. “And reality is less than television.”

Substitute television for social media and ask yourself how many of your friendships have started or been fostered on a Meta platform. Our entire university experience has been slowly swallowed up, and we have given the perpetrators our silent, submissive consent. What choice did we have? Yes, we did kneel to their terms and conditions, but not out of agreement. We were simply faced with the ever-present fear of missing out.

I spoke with SRC General Secretary and ALP Club President Grace Lagan, who conceded that clubs and societies are reliant upon the technology, despite the fact that she believes “social media companies like Meta are deeply destructive social ills” and wishes that she “never had to use them.”

“For first years especially, or people [trying to join clubs] who don’t have existing connections outside those platforms…you’re caught in this bind because you have to use these apps,” she said.

Grace assures me that there are solutions though. Referencing Jenny Odell’s How to do Nothing (2019), she highlighted the rise of sites such as Scuttlebutt – decentralised social media platforms where user data is not held by a single company or database, and thus isn’t monitored like on Meta platforms. “Of course, the problem is that you’d have to migrate everyone onto these platforms,” she sighed. “Beyond alternative social media, I honestly don’t know what the answer is.”

Neither do I, but our conversation left me with a sliver of optimism. Transitioning away from the status quo to a more suitable alternative wouldn’t be easy, but it wouldn’t be impossible either. The oligarchs who own these platforms prey on our insecurities, on our need for friendships and connection. If we were to transition away from them, all it would require is collective and organised action. We’re not in too deep – we can still pull our heads out of our devices and send a message to Zuckerberg and his ilk that we are not as addicted to their software as they want us to be.

Hold that thought for just a moment. My phone is buzzing – everybody’s liking my recent post on Instagram. The notifications are pouring in, and my pre-posting anxiety has been quashed. I feel good – happy even. I have value. The temptation to step back and postpone that transition is palpable. What if I were to stay here for just a moment, on my knees, with my head in the fleeting euphoria of the Metaverse? Let it control my mind – it’s not like I’ll need my body.