If you have tuned into the news this past month you’ll know cheesy 80s-cold-war portrayals of Russians as bond villains, bandits, and general baddies are back in vogue. It certainly is no secret there has been a renewed rush to condemn all things Russian.

I am not a geopolitics expert, so I’ll make like Basil and not mention the war. However, I will explore the ‘third front’ in this conflict — the one concerning culture — and evaluate the West’s cultural boycott of Russia.

The idea that a solely economic boycott is insufficient in disempowering a state is nothing new: cultural boycotts were successfully waged against apartheid South Africa, and continue to be waged against Israel for its own apartheid state and occupation of Palestine. The premise behind a cultural boycott is that the arts are a tool of statecraft — they legitimise ideology, the authority of heads of state, and their politics. While the current cultural boycott of Russia understands this premise, it fails to undermine the state without harming the individuals that live within its domain.

In the week following the invasion, Glasgow Film Festival categorically dropped all Russian titles from its lineup — including No Looking Back by Kirill Sokolov and The Execution by Lado Kvataniya. Both directors have openly condemned the invasion of Ukraine. Sokolov has Ukrainian family himself, and Kvataniya is no friend of the Russian state either, having worked among various dissident artists and experienced censorship. Such a decision was also mirrored by the European Film Academy, though the Venice, Cannes and Berlin Film Festivals have refused to ban Russian filmmakers, instead excluding only official representatives of the Russian state. The latter is more effective as it delegitimises allies and agents of the Russian state instead of its citizens.

Such exclusion of independent Russian artists stands in stark contrast to the aims of the cultural front of the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) and Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel (PACBI) movements. The protest movement wages against the Israeli state and urges the boycotting of projects “commissioned by an official Israeli body” or those that seek to normalise the occupation of Palestine.

For example, in response to the Israeli embassy granting $20,000 to the Sydney Festival, residents and artists alike took part in a similar boycott. This was an effective way of protesting the idea that Israel can engage in the arts whilever it instigates a genocide.

If a movement manages to protest a state as oppressive and genocidal as Israel without arbitrarily censoring independent artists, surely the same can be achieved in the case of Russia.

While cultural boycotts of Israel such as BDS have been waged for decades, this Russian boycott has only been in place for the last few weeks at the global scale, though Ukrainians have protested Russian aggression for years. Lacking the same programme or ideological basis for the boycott as BDS or PACBI, the movement fails to articulate any aim other than to paint Russians — not Russia — as our ‘enemy’.

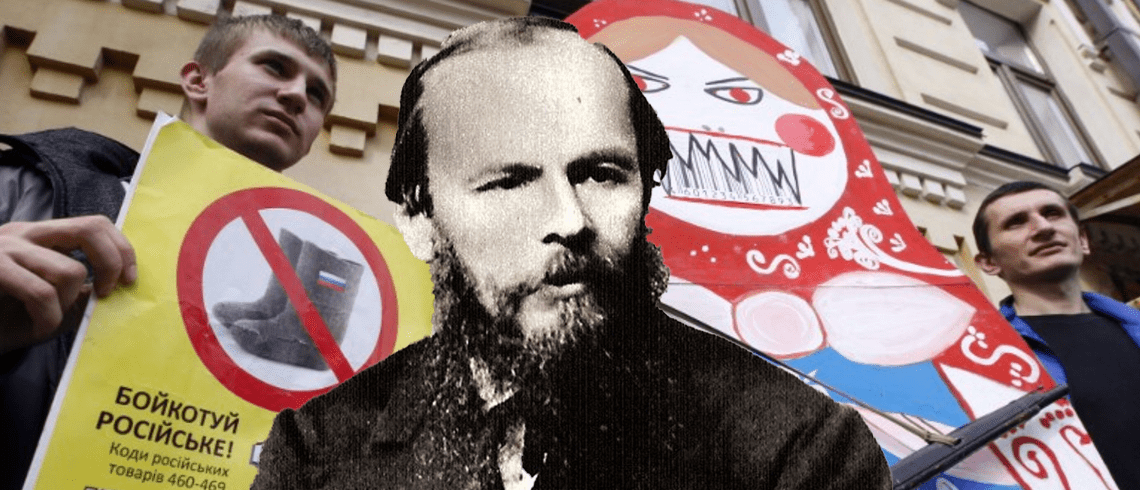

This confused approach is exemplified by the targeting of dead Russians. Earlier this month, the University of Milano-Bicocca made a sudden attempt to cut a Fyodor Dostoevsky course to “to avoid any controversy”, as described by Italian writer Paolo Nori. Beyond the fact that Dostoevsky was evidently no fan of the Russian state, having been arrested, imprisoned in Siberia, and sentenced to death, he’s also been dead for over 140 years. Such a case of university management taking any opportunity to cut arts courses may sound familiar to University of Sydney students, as will the combined staff and student protest which successfully reinstated the course. The Polish National Opera too, has canned a production of ‘Boris Godunov’, an opera even more ancient than ol’ Fyodor. If anything, these Russian works of art frequently produce nuanced discussions of morality, suffering, and power that should be studied closer during times of conflict.

So, what is next? Banning Malevich? Pussy Riot? Tarkovsky? I’ve spoken too soon; the Filmoteca de Andalucía has already replaced a screening of Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris with the American version directed by Steven Soderbergh. Emerging as a director during the Kruschev thaw, Tarkovsky was accustomed to screenings being highly political affairs; works of his such as Ivan’s Childhood convey explicitly anti-war sentiments, making his cancelling even more perplexing.

If we wish to remove all things Russian from cinema in backlash to Putin’s war then so be it. But we can also kiss goodbye film schools, documentaries, almost all types of montage, the Kuleshov effect, editing in general, Hitchcock — all Russian cultural contributions that could be just as arbitrarily boycotted.

An effective cultural boycott of Russia would mirror that of the BDS movement. Rather than incoherent cancellations of film screenings, studies of classic authors, and performances by aspiring musicians, our institutions should be refusing to work with state-backed (or supported) cultural projects. If we want to stand with the Ukrainian people under attack and the Russians protesting this invasion, our actions need to be meaningful and directed rather than a renewal of McCarthyism. Celebrate Russian and Ukrainian film alike. Go watch the ballet. Dust off that copy of Crime and Punishment. Remember: this power struggle over art is indicative of its significance, so keep a critical eye and take the words of another great Russian and “read, read, read.”