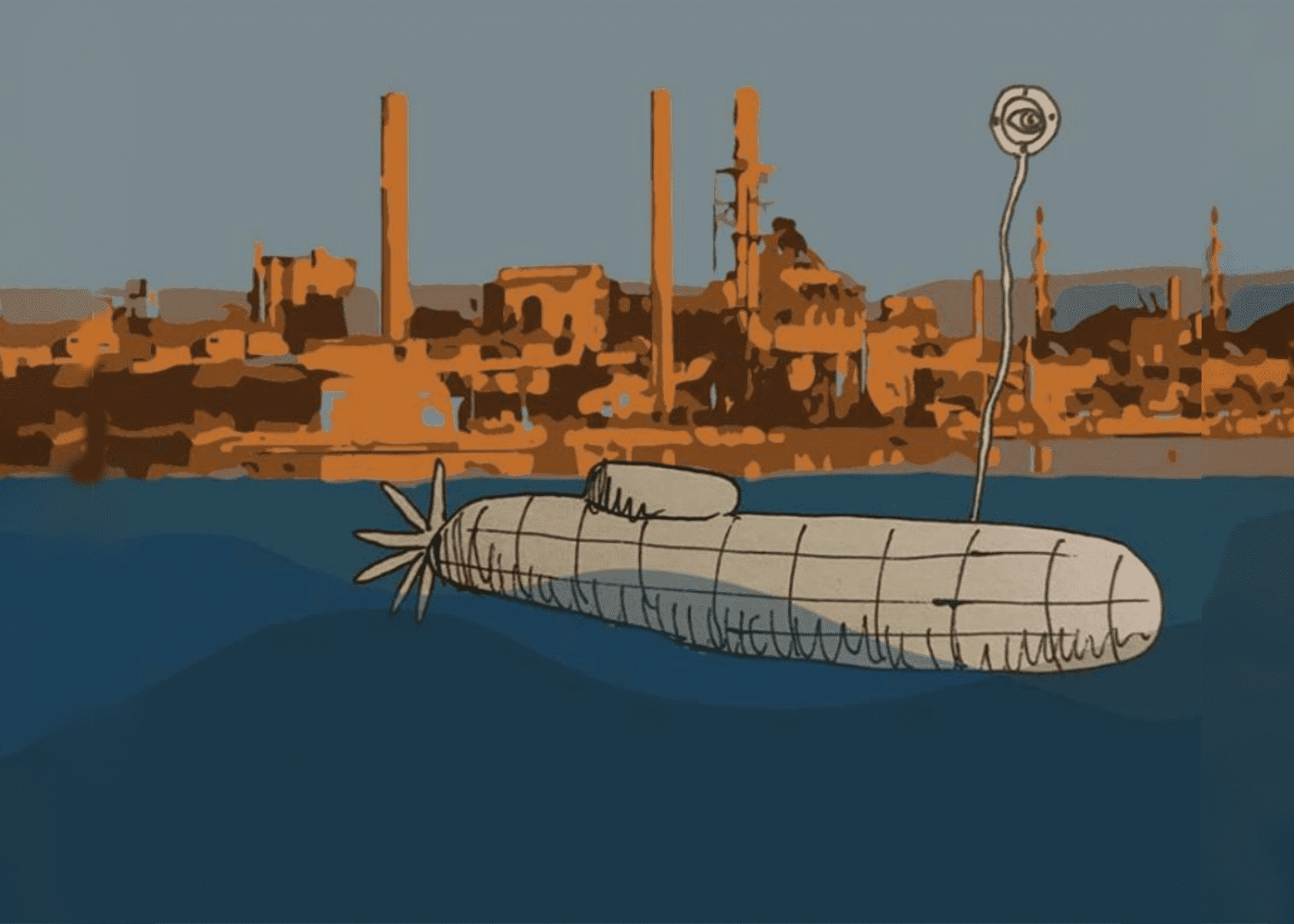

Earlier this year, Port Kembla, along with Newcastle and Brisbane, was announced as a potential location for a nuclear submarine base to house the nuclear submarines purchased under the controversial AUKUS deal. Liberal Senator Concetta Fierravanti-Wells, who grew up in Port Kembla, described Wollongong as “the obvious choice” for the base.

The announcement is hardly definite — a location has not been finalised and the government has been reluctant to enter into precise details about the deal.

All the same, some Wollongong residents have already made their opposition clear.

Secretary of the South Coast Labor Council, Arthur Rorris, told the Illawarra Mercury that: “We will fight tooth and nail to prevent a nuclear target on our city.”

Wollongong has a longstanding opposition to militarism and nuclear proliferation. In 1938, workers at Port Kembla went on strike to protest the shipping of pig iron to fascist Japan, knowing it would be used in their invasion of China. In 1980, Wollongong Council voted to become a nuclear-free city, although that commitment is largely symbolic.

Greens candidate for Cunningham in the upcoming Federal election, Dylan Green, was decisive in his opposition to the proposal in a statement to Honi: “The case for this submarine base is extremely weak.”

In particular, Green condemned the lack of consultation of the Wollongong community before the announcement, telling Honi, “There has been no consultation with the local community in developing this proposal. I wonder if the Morrison government has simply named a few possible sites for the base and is now waiting to see which community hates the proposal least.”

He expressed concern about the military escalation the base could entail, suggesting that superpowers like the US and the UK would treat it as their own, a consequence of the purported “interoperability” of the base. “I do not want my community getting caught up in an arms race,” Green said.

The Labor Party has broadly supported the AUKUS deal, with their critiques largely focusing on demands for the submarines to be manufactured in Australia and, in the case of Cunningham candidate Alison Byrnes, the lack of consultation of the community. Byrnes did not respond to a request for comment in time for print publication, but told ABC News earlier this year that Wollongong deserves “to have all the details.”

Although it is impossible to gauge the level of community support for the proposal at this time, it is clearly a fraught prospect. The justification for the plan seems largely to sit within its potential for job creation, with proponents claiming that 7,000 new jobs will be generated by the base.

This raises broader questions about the ways our elected representatives engage with Wollongong’s changing economy.

Port Kembla has long been a hub of industrial activity. Anecdotally, growing up in Wollongong, it was rare for a friend not to have a relative who had been employed in the Port Kembla Steelworks. The Steelworks was a central destination for post-war migration and provided education, employment and upwards mobility to thousands, like my grandpa.

In 1980, the Steelworks, either directly or indirectly, accounted for around 70% of economic activity within the region, with over 20,000 employees on the BHP books. Now, BlueScope Steel employs around 3,000 people directly and 10,000 indirectly, of a total population of around 300,000.

An outline of the Steelworks — with its chimney stacks topped by glowing flames and plumes of steam — has been a fixture of the horizon of my childhood. I watched the demolition of the iconic Port Kembla copper smoke stack out of the window of my Year 9 history classroom. Visiting BlueScope Steel was a standout primary school excursion. These elements of Wollongong’s industrial past are ubiquitous, yet distant. Evidence of the shrinking of the city’s industrial workforce is ever-present, not least in the 11.7% youth unemployment rate within the Illawarra and Shoalhaven region.

This is not to romanticise the Steelworks. In their heyday they caused indisputable damage to the local environment and people’s health. All the same, deindustrialisation of the region has offered an uneven and insecure future for many.

It makes sense, then, that 7,000 prospective jobs may appeal to many in the community.

We have to think carefully, however, about the hidden costs of the proposal. A military base at Port Kembla expresses a distinct vision of the city’s future, one that many residents may not be happy with.

Dylan Green told Honi, “The opportunity cost of such a proposal is also conveniently ignored. Port Kembla is ideally positioned for the transition to renewably-powered industry: we have an existing steel industry, established heavy transport routes, and the Newcastle to Wollongong coastline has some of the greatest wind energy potential in the country.”

The Illawarra, with its physical geography, industrial past, and the presence of the University of Wollongong, is well-placed to be the site of a just transition. That transition should think bigger than dragging us, sans consultation, further into the fold of global militarism.