Election season is upon us. For many of us here at the University of Sydney, the first thought that comes to mind are the upcoming federal elections in the next two weeks. However, ours is not the only country that will be heading to the polls in May. Over in the Philippines, millions of Filipinos will be casting their vote to determine the future of the country.

The Philippines and its political climate stand in stark contrast to the one we’re familiar with in Australia. The race for the presidency will significantly shape the state of the country — and indeed, Philippine democracy — for many years to come.

Although 9 May will see the election of a number of political offices across the country, the most visible (and arguably, the most important) of these is the race for the presidency. The outgoing president, Rodrigo Duterte, was elected in 2016, and whose term is marked with controversy. Under his leadership, the country has suffered greatly; his so-called ‘drug war’ has led to thousands of deaths from extra-judicial killings and a number of human rights abuses, and his mismanagement of the COVID-19 pandemic has created a host of health and economic issues for the country.

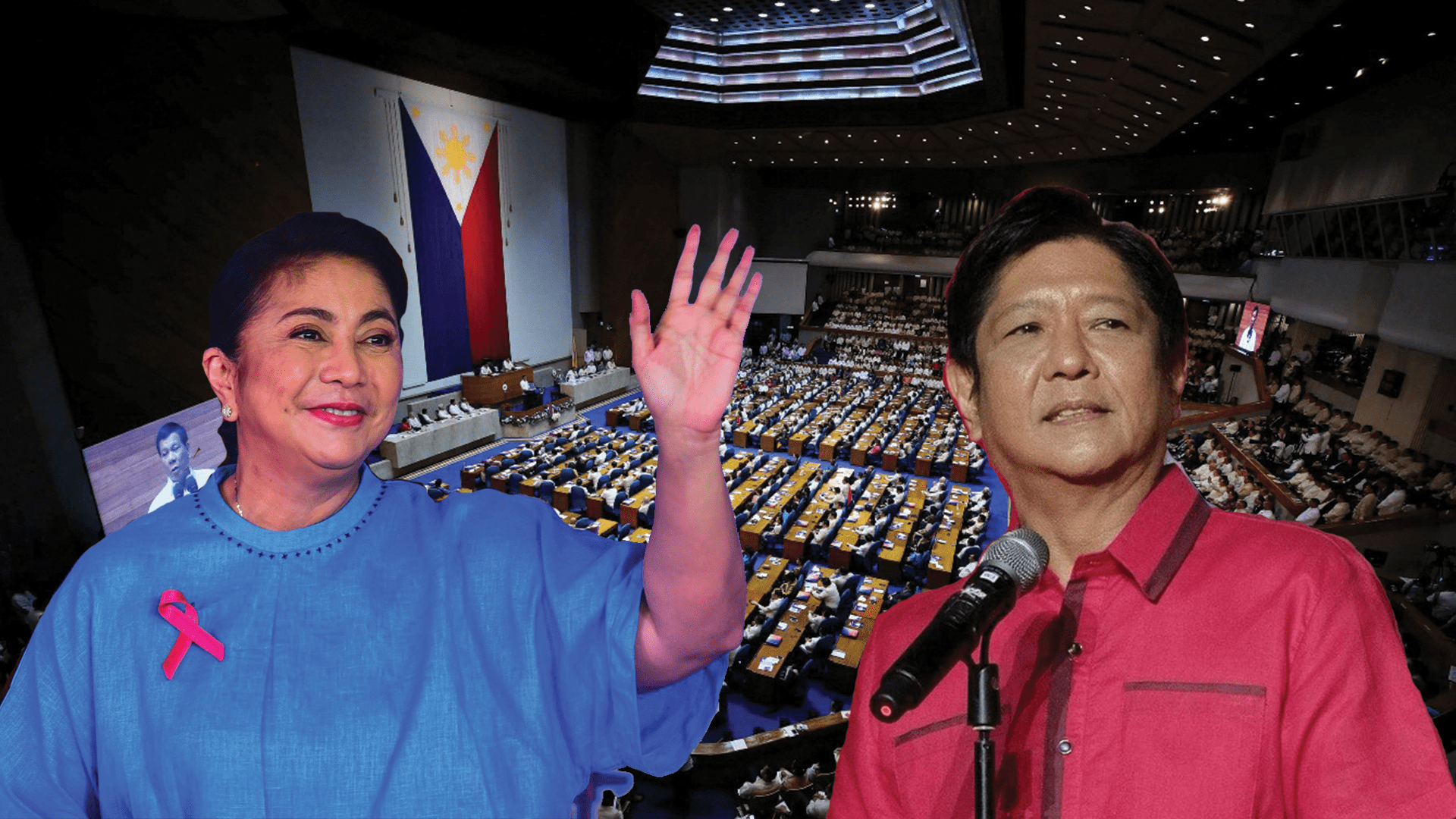

Fortunately, Duterte is constitutionally barred from running for a second term. There are ten candidates vying to succeed him. Whilst the sizable pool of candidates may seem like an indicator of a healthy democracy to first-time spectators, the real competition lies between the two frontrunner candidates – Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., and Leni Robredo.

Who are the frontrunners?

With more than half of total voters’ support, according to recent polling data, Bongbong Marcos is currently in the lead. However, his bid for the presidency has been highly contentious, especially considering he is the son of the country’s former dictator, Ferdinand Marcos.

The Marcos regime, which lasted more than twenty years from 1965 to 1986, is widely considered to be one of the darkest periods in the country’s history. Although Marcos is notorious for his imposition of martial law, his dictatorship was also marked with a number of summary executions and other human rights abuses, rampant corruption and improper use of public money, and an overall erosion of Philippine democracy.

Concerningly, Bongbong Marcos has chosen Sara Duterte as his running mate (his preferred Vice President), who is the mayor of Davao City and the daughter of the outgoing president.

Trailing behind in the polls with just 23 per cent of voter support is current Vice President Leni Robredo, who is running with Senator Francis “Kiko” Pangilinan. In the 2016 elections for Vice President, she triumphed over Bongbong Marcos, who had also been a candidate, with a slim margin of only 0.16 per cent.

“Robredo appeals to more of the younger generation,” says Vince de Guzman, an international student and part of the executive team for USyd’s Filipino Student Society (USyd FiloSoc).

“It’s a breath of fresh air,” Alex Pobre adds, another international student and USyd FiloSoc’s Vice President. “Compared to the other candidates, she’s the one with a clean track record, with so many achievements, with solid credentials.”

With a number of high profile endorsements from various celebrities, university and college heads, and social media influencers, Robredo frames herself in stark opposition to the Marcos-Duterte alliance as the preferred candidate of the youth. Why is this the case? What are the most pressing issues for young people heading into these elections?

Students in crisis

“There is a crisis in education right now,” says Polynne Dira, editor-in-chief of the Philippine Collegian, the student newspaper of the University of the Philippines (UP).

“It’s really getting bad right now because of remote learning. Most of the schools in the Philippines have adopted remote learning, but not all students, and actually some teachers, don’t have access to internet,” says Dira.

“Even though we have public schools, they’re not equipped for a time like this. They don’t have proper internet connection, so they really have a problem continuing education and with the quality of that education. We just do everything to pass, and not really learn at all.”

As well as worsening the digital divide, the shift to remote learning has also exacerbated existing issues at universities, which has seen students struggle to enrol in high demand (often mandatory) courses. Last year, the Collegian reported on a host of issues associated with remote learning within UP, including cuts to class sizes that would lock students out of mandatory courses, insufficient faculty numbers to adapt to changing demands, and a lack of government funding for the University.

Dira also says that the Philippines is “lagging behind” in terms of its education system, with students returning lower results in key competencies. In a report by the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), the Philippines ranked the lowest out of 58 countries in international assessments for mathematics and science. It scored 297 in mathematics and 249 in science, which are much lower than other participating countries.

“The current administration is so proud. They say that we’ve continued learning despite the pandemic, but are we really learning?” questioned Dira.

International students who have left the country in pursuit of education beyond the Philippines aren’t faring much better, either.

“First of all, education is so expensive for us international students,” says Pobre, with a self-deprecating chuckle. “Right now, are there actually benefits for us from the [Philippine] government for studying abroad? None, right?” she asks.

“No, we don’t have any help from our government,” de Guzman replies. “As for the Australian government, I’m not sure how much help they’re giving us.”

Not much, unfortunately. As Honi has reported, international students have been amongst those hit hardest by the pandemic – border closures have locked students out of on-campus learning for almost two years, international students were neglected in the 2020 JobKeeper package, are systematically exploited in the workplace, are ineligible for concession Opals, and most recently, are facing further roadblocks from the Home Affairs Minister if they wish to change courses.

“Generally, other societies at the University, for example the Indonesian or Malaysian Society, actually get support from their consulates. But for us, the Philippine Consulate doesn’t even care,” says Pobre.

Whilst these are all pressing issues for students, there is a larger problem yet that threatens to derail the outcome of the elections, and indeed, the state of democracy in the Philippines itself.

The mysterious wealth of the Marcoses

The biggest threat that all three students identified was the ongoing disinformation campaign spreading through social media. Over the last decade, especially after Duterte became president in 2016, disinformation has increased over the internet.

“For every news article from a reputable media organisation, there are three fake news,” says Dira.

One particularly concerning story attempts to rewrite Philippine history by attributing the wealth of the Marcos dynasty to the fictional Tallano royal family, who apparently paid the older Marcos large sums of gold in return for his legal services. In reality, the Marcoses’ wealth resulted from the rampant misuse of public money during Marcos’ dictatorship, which saw him and his wife Imelda fill their pockets far beyond the legal amount for a president. This theory has been debunked several times over, especially by independent news site Rappler, although it continues to shape the minds of many Filipinos in the lead up to the election.

“It’s absurd, but many people believe it because it’s not really talked about in school. It undermines the history books,” says Dira.

A 2021 poll from Ulat ng Bayan revealed that 63 per cent of the population had internet access, with 99 per cent of respondents using the internet to check social media. It’s not surprising, then, that Facebook and the incumbent government has come under fire for the proliferation of false stories, not just on the Marcoses, but also on Duterte and the current administration. Last year, the Collegian did a three-part series of reports examining the role of Facebook in slowly undermining Philippine democracy.

“I think the media has learned how to fight back, or at least a firm stance against Duterte,” Dira says. “Back then, during Aquino’s presidency (Duterte’s predecessor) or even in Duterte’s early years, the media has just been reporting what has been said.

“But then Duterte resorted to targeting journalists, shutting down media outlets, and harassing reporters. That pushed the media to think that journalism should not just be reporting… For reporters who are following Marcos’ campaign, they don’t just report what he’s saying. They provide context and they fact check it,” she says.

Students have also been on the frontlines to push back against the growing popularity of Bongbong Marcos and Sara Duterte, in various capacities. Making up 56 per cent of the eligible voting population, according to the Commission on Elections, students have a significant role in deciding the outcome of the elections.

What are students doing to fight back?

Although Pobre and de Guzman express some regret in not being present in the Philippines during such a pivotal time for the country, they both share a strong sense of responsibility to participate in the elections.

“Since we’re far from home, we’re utilising whatever we can to fight disinformation and fight for our advocacies,” says Pobre. “Most of the time, for us offshore students, it’s social media use – we use our profiles to support who we want, and encourage people to stay informed.

“For example, Vince and I are part of FiloSoc. We’ve been posting publication materials on our websites and pages about the elections,” says Pobre.

“When it comes to elections, I feel like it’s fair not only to think of ourselves, but of our countrymen back home,” adds de Guzman. “The least I can do is to support who I want to support.”

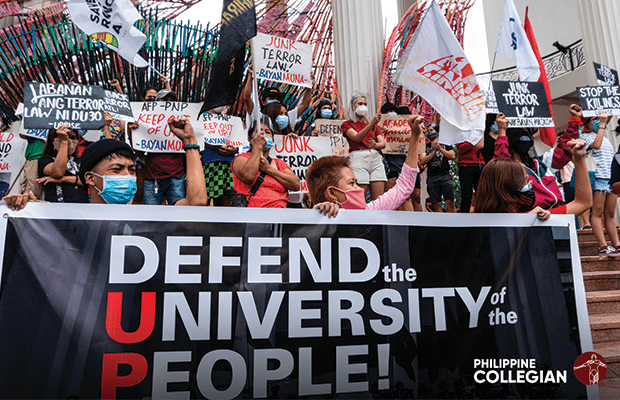

Over in the Philippines, student activism is alive and fully mobilised to support Robredo and Pangilinan.

“Right now since it’s the elections, all efforts are going towards campaigning for Leni [Robredo]. Student activists have endorsed [Robredo] as president and Pangilinan as the vice president,” says Dira.

“Students are also the main campaigners for this election, since they are the ones who do house-to-house campaigning. There’s a lot of them, and since they have the energy and capability to do so, they are really key in strengthening the campaign.”

As of February, more than two million people had signed up as volunteers for Robredo’s campaign; most of them are young people, and some are not yet old enough to vote. They campaign on two fronts: on the ground where they go door-to-door and attempt to convince their neighbours to vote for Robredo, and online to combat disinformation. With both the passion to participate in physical campaigns, as well as the digital literacy to navigate the treacherous waters of social media, young people are well placed to support Robredo.

Although much of activists’ efforts are directed towards the upcoming elections, Dira also describes the vital state of student activism more broadly, especially in organising protests and rallies for various issues on campus and in its surrounding communities. She says that many of these movements are pushed forward by various youth groups, who have different chapters in different regions within the Philippines. Much of them have become a fixture of campus life at UP.

“The League of Filipino Students (LFS) are really the main ones on campus. During the pandemic, there has been a lot of membership in those groups. We were all tired of the government at the time, and a lot of students realised that they needed to act,” she says.

The LFS was formed in 1977 during the time of martial law under Marcos’ dictatorship, originally to protest tuition fee hikes and school repression, before coalescing into a national democratic mass organisation in 1982. Its website outlines its basic principles, including replacing the current “colonial, commercialised and reactionary” education system with a “nationalist, scientific and mass-oriented education”, as well as uniting students with workers for “genuine agrarian reform and national industrialisation”.

Dira continues: “The student activists in UP have also been active in organising the community around UP, so it’s not just about students. For example, when a community is facing threats of demolition, they urge the residents to form a group. The student activists are really the key people in terms of organising.”

As the editor-in-chief of the Collegian, she also spoke about the role of the paper in fighting for the interests of its readership, especially as voting day approaches.

“Historically, we haven’t been active in endorsing any politicians,” she says. “Our coverage focuses on the key issues of the different sectors within the Philippine space. For example, for the urban poor, it’s decent living conditions and housing. For the workers, it’s wages. For the farmers, it’s land and genuine agrarian reform.

“We’d rather focus on those issues that we’d like the candidates to be facing whenever they become president.”

Similar to Honi Soit, the Philippine Collegian is student-funded and has a long history of progressivism and activism. During the martial law period, the Collegian went underground and operated as a mosquito press, after Marcos (the dictator) imposed a widespread media blackout on organisations that published critical stories of his regime’s many abuses.

Dira describes its political ideology as “national democratic”, which is the dominant left-wing movement in the Philippines. Its main analysis is that the root cause of social inequalities is the “semi-feudal, semi-colonial” nature of Philippine society, and that liberation can only be achieved through national revolution against “the three evils” of imperialism, feudalism and bureaucratic-capitalism from the masses.

“We’re different in that we are not beholden to the interests of businesses (in the same way that mainstream media is). Rather, we are beholden to the interests of our readers – students and the community around UP,” Dira says.

“You can also differentiate the Collegian because it practices advocacy journalism. We don’t really pretend to be objective when we cover issues. We analyse them, and we already have this certain lens that we apply. And we campaign actively for the solutions that we want.

“We don’t only present the problems. We also actively critique them and put forward solutions about these issues,” she says.

The future for students

Election day is right around the corner, on Monday. Months of campaigning, organising, education and fighting lead up to one single day that will determine the course of the country for the next six years. And students, as amongst those with the highest stake in the election outcome, will be a force to be reckoned with.

“The students make up more than half of the electorate. Whoever the students support will be important, says Dira. “It’s gonna be us who suffer if Marcos wins.”

“It’s for our future,” de Guzman says, when I ask why it’s so important for students to get involved.

“You don’t just vote for a candidate for what they can do in the present. You also vote for what they can do in the future.”

By the time this article is printed, the world will know who the next President of the Philippines will be. Given recent opinion polling, widespread disinformation across the country, and structural factors deeply entrenched within the current political climate, things are looking pretty dire. But regardless of the outcome, we can be assured that there will always be young people who care deeply about their future, who are ready to fight for a better nation.