“They are not civilised, they are barbare,“ a relative of mine said in a conversation some years ago during a family reunion. They were referring to Vietnam’s Cham people, an ethnic minority primarily based around central Vietnam.

Barbare is French for ‘barbarian’.

Little do they know, those were the very same words that France used to depict them less than a century ago.

“Crescam Paulatim” or “little by little we grow” was Saigon’s motto until the outbreak of WWII, imposed by a racist colonial administration headed by Pierre-Paul de la Grandière after Vietnam fell to French control.

The irony is unmistakable. It was discrimination in broad daylight yet barely anyone recognised my relative’s comments as such, and if anything, tacitly or actively partook in it.

These beliefs are undoubtedly the byproduct of a socially conservative upbringing.They were reared in during the heady days of the 1960s when Diem’s ultra-conservative Catholic nationalism led the country. However, these attitudes are not confined merely to Cham communities but at times, to Hoa or Vietnamese-Chinese communities, with one Hoa friend recounting their experience of being bullied for their identity — with tension coming from Vietnam’s fraught relationship with China.

It’s a reminder that casual racism remains rife even in communities that endured the ravages of colonialism. It employs the same classist dynamic that characterises white supremacy, namely, the elevation of a false sense of superiority over others. This sense of superiority masquerades itself as nationalism.

Though it is undeniable that Vietnam endured an extensive history of discrimination, I am also standing on the relics of historic cultures, but not of my own. Travel up north from Saigon and you are greeted by My Son Sanctuary, Nha Trang’s Po Nagar complex, Phan Rang (formerly Panrang) and numerous others. In these cities lie some of the last remaining remnants of Champa. This is not accidental — they were systematically excised from power nearly two hundred years ago — dating back to the first half of the 19th century.

With annexation almost always comes cultural assimilation, or worse, destruction. The same can be said about Vietnam’s experience as a tributary partner of imperial China over several periods within the past millennia. Anya Doan’s article on the Trung Sisters’ rebellion in 1st century Vietnam, for instance, is a glimpse of the sinicisation that continues to be expressed in the Confucian cultural customs deeply embedded in Vietnamese history and culture.

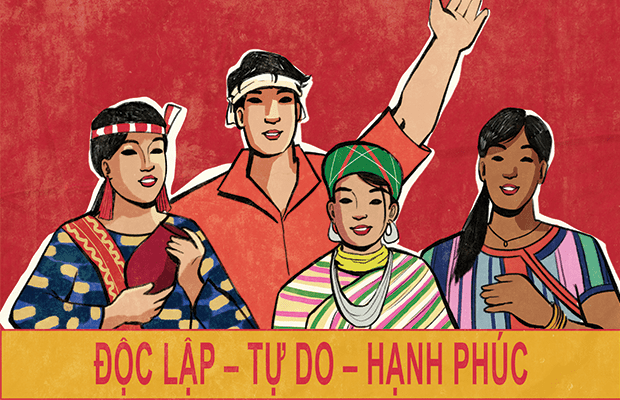

Although some will say that these examples are ancient and obsolete today, they are more contemporary than is acknowledged. Minority cultures are often relegated as just another artefact of history, put to the wayside in museums rather than as a core participant of the national conversation.

To meaningfully pursue anti-racism, then, our communities need to challenge the pervasive classist and racist portrayals of ethnic minorities as opposed to buying into conservative conformity. This means throwing polite sensibilities out of the window and ready to challenge these stereotypes, either privately or publicly to the individuals or institutions that perpetuate them.

Although the national discourse back home in our respective cultures is largely detached from identity politics seen in English-speaking spaces, the tools at our disposal are often more confrontational than we give credit to, criticisms that tear at the heart of racism. In the Vietnamese context, racial discrimination is often referred to as ‘Nạn kỳ thị chủng tộc’, roughly translating to ‘the disease of racial discrimination’ in a constant reminder of the gravity of the issue.

This work cannot and should not stop at the individual. It extends to a need to steer away from an insistence on cultural homogeneity. This includes incorporating Cham and Hoa communities in the ‘we’ in our history books rather than as outsiders, it means recognising that, whether diaspora or a minority, community achievements are recognised rather than seen as a foreign curiosity. Until we extract the nail of the insidious discrimination that happen to ethnic minority communities back home, the spectre of toxic nationalism will remain at the back of our collective consciousness.